Opportunities For Post-Brexit British Companies Along China’s Belt And Road Initiative

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

A post-Brexit Britain has not at present been able to secure many trade agreements in Asia, while political differences have developed concerning China. This diplomatic and trade gap become especially apparent with the EU agreeing a Bilateral Investment Treaty with Beijing at the end of last month.

Meanwhile, China has placed its Belt and Road Initiative at the heart of its Foreign Policy, placing it at the centre of its updated Foreign Aid Programme and re-stating it is a core pillar of its foreign trade policies. This comes after years of media criticism about China’s intentions, mainly concerning the imposition of debt traps and sovereignty issues riding over the trade benefits that the infrastructure build has given. These can now be discounted, with the UK’s own Chatham House stating that there was in fact, no evidence of debt trap burdens being placed on other nations as a result of China’s lending. The same institution has also just released a blueprint paper, ‘Global Britain, Global Broker‘ arguing for a post-Brexit role for the UK as, among other agendas, a “Champion of equitable economic growth.”

But how does this fit in with China’s Belt & Road Initiative?

While China’s BRI is not a Free Trade bloc, countries who have signed off an MoU with China concerning this have seen some benefits in increased trade and investment. In terms of the EU, member nations of that who are also signatories of BRI MoU saw their 2019 exports increase by 5% more than EU members not part of the BRI. Part of this is improved infrastructure, part of it China trade.

China’s Developing Free Trade Agreements: The Africa Example

An oft-unnoticed aspect of the Belt & Road Initiative is that China has been developing its soft infrastructure – and especially in the development of new Free Trade Agreements and Special Economic Zones, all designed to reduce the tax and tariff burden. Recent additions to this network are the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which China helped broker and reduces intra-African tariffs to zero on over 90% of all products and which came into effect on January 1 this year. That makes sourcing of component parts across Africa far less expensive and cumbersome than before, and that of course applies to all businesses with an interest in Africa.

With the provision of Chinese built Special Economic Zones, a new Free Trade Agreement with Mauritius to act as an offshore Gateway to Africa, and Foreign Minister Wang Yi’s successful January trade visit to Africa last week, we can begin to understand from the African example just how expansive the Chinese have been in developing trade routes across the globe. Of note to British investors in this regard is that the UK does have trade agreements with SACUM (Botswana, Eswatini, Lesotho, Namibia, South Africa, Mozambique) and ESA (Mauritius, Seychelles, Zimbabwe) and a Double Tax Treaty (although not a Free Trade Agreement) with Mauritius. The point being that Chinese initiatives in Africa have made it easier for businesses for other countries to operate there too.

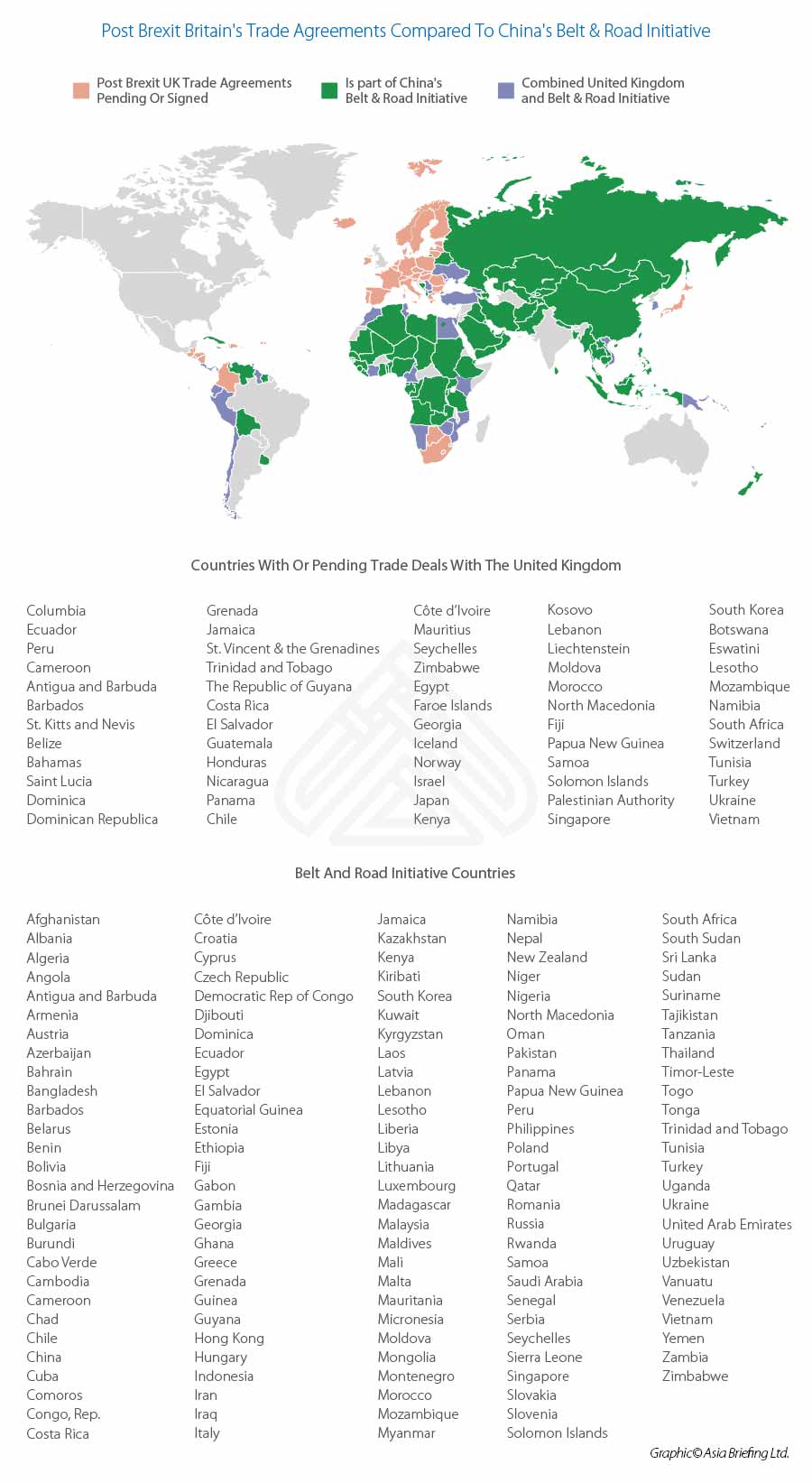

We can see where China’s Belt & Road Initiative is when compared to the UK’s current trade reach in the map below.

UK Access To RCEP, ASEAN & Russia – Via China

There are similar opportunities elsewhere. China has signed off the recent Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, which includes all ten ASEAN nations as well as Australia, New Zealand, Japan and South Korea. This brings benefits to foreign investors in China, an issue we discussed in the article RCEP FTA Signed, What Can Foreign Investors in China Expect?

ASEAN the South-East Asian trade bloc, includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam. Of these, Brunei, Malaysia and Singapore are members of the British Commonwealth, while the UK has signed off trade deals with Singapore and Vietnam.

ASEAN’s collective GDP in 2019 was about US$9.34 trillion, roughly equivalent to that of the entire Commonwealth and three times larger than that of the UK itself. ASEAN is a market of about 135 million middle class consumers (24% of the total population) and is expected to double in size in the next decade. It is one of the global trade development drivers, yet the UK’s engagement with it is minimal.

ASEAN nations meanwhile, apart from enjoying Free Trade amongst themselves, also have Free Trade Agreements in place with China, India, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea.

While Singapore is a wealthy market and a prime position for UK financial services and products, acting as the de facto financial capital for ASEAN, the Vietnam market provides opportunities for British companies who may wish to have an alternative to China, and especially in export manufacturing to service China itself, India, the other ASEAN nations, and the EU. Vietnam signed off an Agreement with the European Union which came into effect from August 1 last year.

Russia like China has diminished in the UK’s political stature in recent years, but that doesn’t mean to say it is totally off limits, and it remains a significant market in its own right. Sanctions mostly affect either specific individuals or Russia’s Oil & Gas sector, while Russia is itself the lead nation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which also includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Collectively, the EAEU is a market of about 176 million people with a combined GDP of about US$5 trillion.

What is interesting about the EAEU is that it has Free Trade Agreements with Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to Serbia, Iran and China. The latter is currently non-preferential; however, tariff negotiations are underway with progress expected during 2021. Russia-China trade is expected to double from now to 2024, hitting about US$200 billion. The EAEU is also currently negotiating an FTA with India, with signs that this is also expected to be completed this year. Russia’s proximity to China should also be of interest; a subject I explored in the article Opportunities For British Businesses In the Russian Far East.

A New China For Britain In 2021

A common question I am often asked these days concerns the Chinese slowdown of overseas financing of the BRI. To which there is a very simple explanation: it’s nearly finished. China’s ODI and foreign policy for 2021 have in fact already been laid out in statements made by Xi Jinping at the recent United Nations summit , by Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the recent Belt & Road Forum and by new Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao at the recent Central Economic Work Conference. All quite clearly state China’s intentions: to focus ODI on more strategic investments, such as healthcare and technology, to take more strategic positions within foreign companies in specific sectors, including minority positions, and to rebalance the Chinese economy by moving it to away from manufacturing to a consumer base.

China spent US$4 trillion on BRI infrastructure – that part of the investment is nearing completion. China has also followed this up by making three strategic changes, introducing a revised foreign investment law last year, relaxing foreign investment in various industry sectors, and introducing a new ‘dual circulation strategy’ designed to spur consumer demand. I summarized these recently in the article A New China For 2021.

It is a British irony that the political situation between London and Beijing has deteriorated at the same moment that China market access has been the best it has ever been.

Therefore, there are many good reasons why British companies should continue to look to China, both the growing consumer market, and access to an extensive Free Trade Agreement Network.

Hong Kong Opportunities

Hong Kong also remains viable, although the market is changing. As my colleague Alberto Vettoretti stated in his Dezan Shira & Associates Partners roundup this week:

“Hong Kong’s geographical location and status (one country – two systems still here till 2047) are its biggest advantages. If taken as a single bloc, the Greater Bay Area would be the 12th largest economy in the world, made from 11 cities with a combined population of over 70 million and an economy which has the 2 billion USD GDP mark in sight (larger than Italy). Hong Kong’s GDP accounted for 20% of China’s in 1997, this has now shrunk to around 3%. Over the same period, China’s growth has been nothing less than extraordinary and while Hong Kong has also played and is still playing an important role in the Middle Kingdom’s success story, it is now time to forget about past glories and start a new phase of proactive engagement across the border.

We have addressed the importance of GBA in previous articles. Please click here and here for additional insights on the subject.

The integration of the cities and economic clusters within the Pearl River Delta is not a new subject. Discussion on how to achieve this challenging goal started many years ago but only recently, following a top-down executive decision by Beijing, the agenda is more coordinated at the very top and this has translated into better communication and projects implementation amongst the different governments in GBA. While the 11 cities in the region will also fiercely compete to attract best companies, talents and projects, Hong Kong could carve out a fundamental role based on its privileged status.

The SAR is the de-facto international aviation hub and offshore financial centre (also the largest global RMB clearing centre) of choice for the region. While the 5 international airports in the GBA will always expand their international routes, only Hong Kong will be the hub with more global connections and networks. The recent investment into the Zhuhai airport is a clear indication of Hong Kong trying to cater for a better and faster integration with Chinese internal routes and provide a seamless experience and journey to those global travelers doing business in this part of the world, particularly with China.

After the recent economic and political challenges in the city, promoting an integrated GBA brand and “concept” would help the whole region grow stronger. Cities rivalry will still be there and would also be beneficial to the overall GBA development but the sooner each city will play its strengths under a synchronized agenda the sooner the bay would become a model of sustainable growth for other regions in the world.”

Exploiting The Belt & Road Initiative

Foreign involvement in Belt and Road projects has been limited, as much of the interest and attention has been on participating in the multi-million-dollar infrastructure builds, and these typically come with Chinese state financing, conditional that Chinese SOEs conduct the work. Chinese BRI projects favor other State-Owned partners rather than public companies, both for business cultural reasons and for keeping details out of public scrutiny; while the sheer nature of Chinese financial competitiveness combined with sometimes superior technology and construction expertise, also plays a part, especially on difficult terrain. China for example built the rail to Lhasa, very few if any foreign contractors have that type of experience.

Accordingly, involvement in BRI projects tends to be limited to Chinese contractors and their local partners where the project is situated. In fact, other foreign investors are missing a trick here, as most of China’s BRI projects are now nearing completion with the infrastructure build coming to fruition.

This creates new opportunities for foreign investors to look at the original purpose of building the project in the first place and the increased commercial business flows this will generate. For example, Sri Lanka’s Southern Expressway was completely Chinese built and financed (with a lot of criticism about the cost). However, that spurred a huge growth in the regional tourism industry. I touched on that project here and about the related Colombo Port City development here which will see Colombo city develop into a Southeast Asian office center for back-office functions. All of these provide investment and service development opportunities for foreign investors.

I can relate to them first hand as I maintain several properties in the southern coast of Sri Lanka. I have personally experienced the developments that the Southern Expressway has brought in and how the Port city development is progressing, and have no doubt that this experience will manifest itself across other BRI projects as well. I described some of these as follows:

- Belt & Road Projects In Southeast Asia That Foreign Investors Should Be Exploiting

- China-Europe Rail Freight Doubles In 2020. These Are The 44 Key And Emerging European Freight Hubs To Watch

- The European Belt, Road, Railways & Ports That EU Investors Should Be Examining

- Central America’s Belt & Road Initiative: How US Investors Can Take Advantage

- South American Belt & Road Projects Foreign Investors Should Be Looking At

- African Belt & Road Projects Global Investors Should Be Aware Of

The message here is that the opportunities lie where the BRI infrastructure build has been completed, there are asset enhancements and appreciations, and international investors can provide the service elements to support the increased trade and human needs the physical infrastructure provides. But very few businesses are looking at this, although our firm provides the market intelligence for them to do so. The penny hasn’t yet dropped, yet there are ways to examine the potential for involvement and exploiting the build.

The main issue is looking at the local financing and regulatory requirements along with local banking issues. These can vary tremendously and especially along the BRI as by proxy most of the countries involved are emerging economies. Investment laws and service facilities may not be as advanced as in Europe or North America. China gets around this by having G2G agreements that are typically worked out at the diplomatic level, foreign private investors may not have this option. So, the first thing to look at are the local investment laws, and what banking services are provided to foreign investors. This needs to be done on a country-by-country basis as not all have the same legal, tax or operational infrastructure. Many do not possess internationally or even commonly traded or exchangeable currencies. Often local laws permit the investment of foreign currency but restrict its subsequent repatriation. I discussed the varying types of legal and regulatory systems deployed along the BRI in the article Corporate Law Standards And Procedures Along The Belt And Road Initiative.

Also, there are double tax treaties that impact upon applicable rates, these can be used to mitigate against profits tax levels. All this needs to be understood before any investment is made. The first thing any business interested in looking at investing in a second country should do is examine the local foreign investment laws, applicable tax treaties and the local regulatory environment and examine the operational aspect of handling financial transactions.

For South-East Asia, and the ASEAN bloc which includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam all these countries have differing foreign investment laws, different currencies, and levels of banking capabilities. All are part of the BRI and there are huge opportunities for exploiting the infrastructure build that is taking place across the ASEAN region. It can be very difficult for foreign investors based from overseas to establish meaningful relations from the US or EU with local banks in ASEAN. However, Singapore is the de facto financial capital of ASEAN and numerous Singapore banks have relations with their ASEAN counterparts. So using Singapore as a base for handling ASEAN investments is sound corporate practice and is a subject we discussed in the article Why Singapore Is A Good Base For Establishing Financial Treasury Centers.

There are similar trade blocs in other parts of Asia, the Middle-East, South America, Africa and Eurasia. So the good news is the regulatory aspect is defined. What needs to be conducted is the local regulatory research.

There are additional risks that corporate treasury departments have to navigate regarding BRI projects, many of which will be familiar to Treasury professionals:

Political risks – the stability of the local government and its credit rating;

Currency risks – especially during these times, assessing currency risks, inflation, devaluation, exchange rate fluctuations and so on all need to be assessed;

Due diligence – checking out the local banks viability, the imposition of any sanctions, and operational ability to conduct business – some countries, including China, are extremely reluctant to process banking arrangements with even legitimate businesses due to the extent of US sanctions.

Ability to repatriate funds.

Ability to access professional firms at standards able to fold local accounts into consolidated reports to HO regulatory standards.

There may also be issues related to trademark registrations if investors are to introduce their brands to new markets. I discussed that in the article Submitting Trademark Registrations Along The Belt & Road Initiative.

While the immediate momentum, scale and long-term timeline driving BRI projects has slowed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Multinationals will increasingly want to take advantage of China’s more pragmatic view on international involvement and constrained ability to be the sole financier of all things BRI. There may have been a slowing of BRI investment right now, but it’s here to stay. China judges the short term by decades, and the BRI is an opportunity for businesses with a longer-term development view. British companies and investors have plenty to consider.

British companies and investors have plenty to consider ahead of belated UK Government involvement. China and its Belt and Road Initiative have changed considerably over the past 12 months, while the UK has been pre-occupied with Brexit. lt is time to re-evaluate the potential, the wide ranging, multi-lateral connections and new supply chains, and assess where the potential really lies.

Related Reading

- Belt & Road Trade 30% Of China’s Total During H1 2020

- China’s Free Trade Agreements Along The Belt & Road Initiative

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com