South American Belt And Road Projects Foreign Investors Should Be Looking At

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China’s Belt & Road Initiative officially kicked off in 2013, some seven years ago, under the initial title of ‘One Belt One Road’. That was later dropped as it became apparent that the scale of demand for projects would be rather more than single Eurasian and Maritime routes.

In terms of South America, the Chinese influence is not as pronounced as elsewhere, mainly as it is farther away and the US political influence is far greater. However, while China’s funding of projects within South America has occurred rather later than in Asia, many are now starting to be constructed.

These include roads, rail and ports. While Washington has not been especially welcoming of Chinese funded infrastructure build close to its sphere of influence, the fact remains that these projects now either on the drawing board, in planning and assessment stages, or coming to fruition, offer Latin American, American and other foreign investors the ability to get involved by exploiting that same infrastructure. This includes property investments, transportation, waste and water management, power, and especially catering for human needs such as restaurants, catering, computer services, tourism and business services and so on.

The World Bank for example recently noted that the massive investment under the BRI can “transform the economic environment in which economies in the region operate.”

We can examine some of the Belt & Road Initiative projects that are about to reach maturity in either being given the green light or reaching completion in South America as examples:

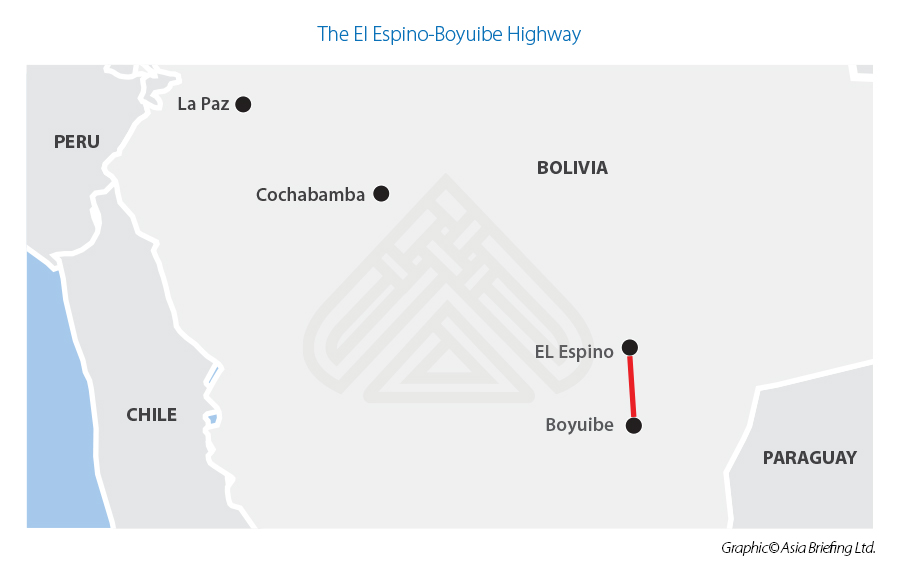

Bolivia: The El Espino-Boyuibe Highway Project – Linking Bolivia to Argentina & Paraguay

A Flagship Project of China’s Belt & Road Initiative (BRI) in South America, the 160-km El Espino-Charagua-Boyuibe Highway will directly link the country’s eastern provinces of Santa Cruz, Chuquisaca and Tarija with each other and with neighboring Paraguay and Argentina. It includes the 306 meter long Parapeti Bridge, one of four significant bridges along the highway, replacing an old wooden single lane bridge. China Railway Group Limited (CREC) was contracted to build the route.

The completion of the highway project – currently over 50% done – is expected to cut the travel time between San Antonio de Esmoruco and Santa Cruz in half. Additional highway plans to further upgrade highway connections to Paraguay and Argentina can be expected in time.

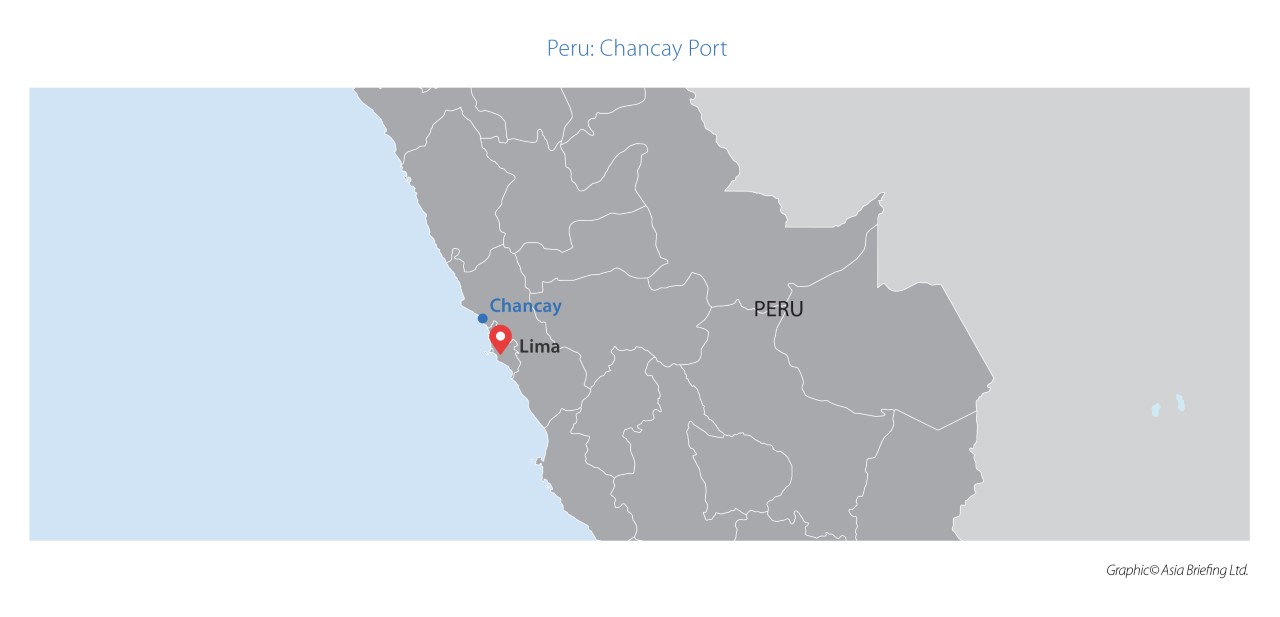

Peru: Chancay Port – Enhancing LatAm Exports To Asia

China’s COSCO, a leader in port terminals management have purchased a 60% stake in Chancay Port, to the north of the Peruvian capital Lima. This is the first operation in Latin America for COSCO, the company is already active in most continents and in particular in Europe through the acquisition of the Greek Port of Piraeus. Additional Chinese investments in Peruvian infrastructure may be planned as Peru and Bolivia expand their rail links. Mineral production from Bolivia may be then exported to China through Peruvian ports.

Cosco Shipping is spending US$3 billion in developing Chancay as a deep-water general cargo port and will increase the Port capacity to 1 million TEU. Work began in April this year. Cosco is already planning to move deep-sea services there to “avoid congestion at Callao” as well as “to bring down costs” and better serve the fast-growing fruit and vegetable exports from Peru. Chancay will be a massive boost for key Peruvian exports such as avocadoes (Peru is third largest exporter in the world), blueberries, guava, oranges, grapes, potatoes, seafood and fishmeal. The main reason the Chancay project will be such a benefit to shippers is that it will help them to drastically reduce costs for many Peruvian exports. This is especially the case for fruit exporters from the central regions of Peru, who have to take the long journey north to Paita, while Chancay will also become an alternative to Callao.

Peru’s fruit exports, subdivided into fresh, frozen, canned, and juice, make up over 50% of Peru’s agricultural shipments and they grew by 9.5% in 2019. Peru has a Free Trade Agreement with China, one of the first South American countries to have negotiated this, and its exports have boomed as a result. Peru’s objective is to diversify its exports to China in sectors other than mining, and in particular in agriculture by developing trade of coffee and alpaca to the Chinese market and Asia overall.

Uruguay: China’s Gateway To Mercosur

China purchases 27% of Uruguay’s exports, with principal items being beef, timber, mutton and wool, with Montevideo Port being one of the best harbours on the South American east coast. It also has ‘Free Port’ status meaning goods can also be re-routed to other markets in South America, such as Paraguay, Bolivia, Argentina and Brazil. The country signed off a BRI MoU with China in 2018.

However, in a rare case of China not winning all its ‘win-win’ deals, the Uruguayan government opened tenders for the development of the Ferrocarril Central Railway linking Central Uruguay’s second largest city of Paso de los Toros with the Port of Montevideo. China’s CMEC-SDH bid however lost to the Uruguayan-Spanish-French consortium Grupo Via Central a year later. But there is more to China-Uruguay and the Belt & Road Initiative than losing railway bids.

Uruguay is the first member of Mercosur, the South American Free Trade bloc, to have signed up to the BRI. Mercosur operations involve free intra-zone trade and a common trade policy between member countries. It is the world’s fourth largest trading bloc after EU, NAFTA, and ASEAN, with an annual GDP of about US$5 trillion. Mercosur is home to more than 250 million people and accounts for almost three-fourths of total economic activity in South America.

With Uruguay now a BRI partner with China, and it being the only Mercosur member to be so, this places Montevideo in a position of some responsibility. China wants access to Mercosur, and ideally a Free Trade Agreement. Uruguay wants the same, but as a relatively smaller economy, with powerful neighbors, needs to be seen to be acting impartially and responsibly when it comes to dealing with China. Uruguay will also wish to enjoy its moment in the sun as regards China-Mercosur relations as todays ‘keeper of the keys’. China has already stated its intentions to double bilateral trade with South America to US$500 billion by 2025 and to increase total investment into the region to US$250 billion. Accordingly, while there may not be mega-construction and billion dollar projects being invested in Uruguay by China just yet – the relationship is highly important, strategic, and worth billions of dollars in future China-LatAm trade.

Chile: The Santiago-Valparaiso High Speed Rail – Connecting The Countries Two Largest Cities

After years of red tape and disagreements, it appears that one of the region’s most anticipated infrastructure projects could finally be going ahead, bolstering regional integration and offering the possibility of streamlined exports from Chile’s Pacific coastline. A high-speed train line between Chile’s capital, Santiago, and Valparaíso – the country’s most important port and the seat of its congress – would facilitate travel between the country’s two largest population centres in under 45 minutes, rather than the two-hour drive the journey currently takes. The two destinations are arguably Chile’s most recognizable, as Santiago is not only considered Chile’s industrial and financial epicenter, but is also of considerable significance from a South American viewpoint for the same reasons, while Valparaiso is a historically significant city for its cultural value and the fact that it is also home to Chile’s second largest port.

A new suggestion for the route and budget of the project was made on February 4 this year with a budget US$1 billion less than its predecessor. The proposal was delivered to Chile’s Ministry for Public Works by a Sino-Chilean consortium called Tren Valparaíso Santiago (TVS), comprising the Santiago-based engineering firm Sigdo Koppersand state-owned China Railways Group Limited (CREC). The tender is only for the construction of the line, and the service would still be run by the state railway company, Ferrocarriles del Estado (EFE).

Álvaro González, the general manager of the TVS group, estimates that the overall cost of the project will be US$2.4 billion, which he asserted would not require any state contribution, unlike the original proposal.

The project would see high-speed trains carry both passengers and freight at up to 200km/h between the capital and Pacific coast. Several tunnels will be built in order to complete the route, which has been the subject of internal feuds for several years and the infrastructure handed over to the winning bidder for a period of 50 years, although it will no longer follow the course of the Ruta 68 highway which had been the initial plan. A ticket between the two cities is predicted to cost around CLP5,500 (US$8), although this would increase during peak hours, and services would run every five to 15 minutes carrying 890 passengers each. There will be the option to buy season tickets and discounted regular travel cards. If approved, the line is scheduled to open in 2024, arriving at Viña de Mar in 39 minutes and in Valparaíso in 45 minutes.

Chile, with its strong economic foundations, already counts China as its largest trading partner, with US$45 billion in goods traded between the two nations in 2018. A final decision to tender the project will likely be made next year.

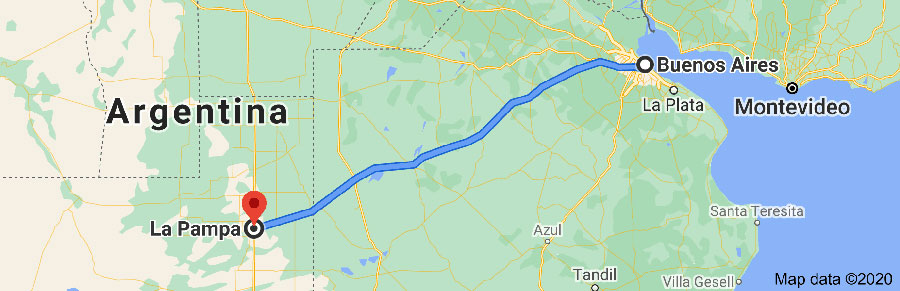

Argentina: National Highway B – Connecting National Industrial Zones With Ports

Argentina is not a member of China’s Belt & Road Initiative, but there are signs it will shortly sign off an MoU. Last week, Argentina became a shareholder in the Beijing majority owned Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, while China Construction America (CCA), a subsidiary of China State Construction Engineering Corp Ltd (CSCEC), recently won the tender to construct Argentina’s National Highway B.

The highway, stretching for 538 kilometers, will link Buenos Aires province and La Pampa province, both major industrial and agricultural economic zones in Argentina. Construction will take five years. It is the first public-private partnership project a Chinese company has conducted in Argentina. The contract amount is U$2.13 billion and grants 10 years to CCA to operate the project after its completion. Improved conditions will mean the current 7.5 hour journey time should be reduced to five. The route should be operational by 2025.

The Bi-Oceanic Road & Rail Corridor: Connecting Atlantic To Pacific Across Latin America

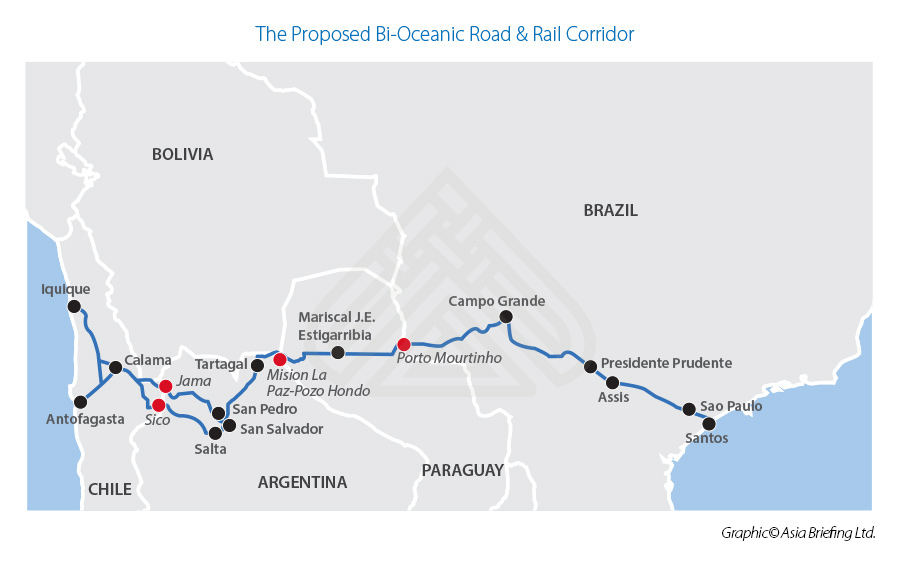

The Bioceanic Corridor is a proposed road and rail project between Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina and Chile. The project would join the port of Santos, Brazil on the coast of the Atlantic with the ports of Iquique and Antofagasta in Chile, on the Pacific Ocean. During his trip to China in 2013, Bolivian president Evo Morales discussed with China’s President Xi Jinping the possibility of building a railway to link the Atlantic with the Pacific through Brazil and Peru. In August 2014, a mission from Bolivia sought financing from the Chinese government. Last year, CAF (the Development Bank of Latin America) and Bolivia signed an agreement for CAF to provide US$3 million in non-reimbursable funds for a feasibility study. The potential for future Chinese involvement in this project will presumably be based on how this study pans out – it is due by 2023.

Exploiting The Infrastructure

These are just a handful of the Belt & Road projects that China is either potentially involved with or actively investing in South America, and in the next few years these will either be approved, with ones under development coming to fruition. It is also unlikely to be the end of China’s BRI ambitions in South America – as projects increasingly reach completion in Eurasia and Asia, Chinese contractors will be looking for new opportunities.

Latin America meanwhile is hobbled by its inadequate infrastructure. More than 60% of the region’s roads are unpaved, compared with 46% in emerging economies in Asia and 17% in Europe. Although China does have some political and diplomatic catching up to do in South America, it will have a huge role to play in putting into place some of that missing interconnectivity. This will mean, over time, more roads, rail, port and other infrastructure investments.

All, however, offer opportunities for both small and large investors to service the human needs of the people that will in time be flocking to use them — and this is where the real benefit to local and foreign investors lies in such BRI projects: exploiting the infrastructure.

We will be continuing to bring readers up to date with these developments, and also provide business intelligence and market research facilities to clients. Please click here to obtain a complimentary subscription and here to talk to us about how to get involved and exploit the assets coming onstream.

See Also:

How US Investors Can Take Advantage Of Central America’s Belt & Road Build

Related Reading

- Developing Global Free Trade: Linking China’s BRI with Mercosur, South America

- China’s Belt & Road Initiative And South America

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com