The Greater Eurasian Partnership: Connecting Central & South-East Asia

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

With the United States set to pull its remaining troops out of Afghanistan on September 11, China and Russia now have the opportunity to install security and build much-needed infrastructure in a long-neglected region.

The success of the joint-China-Russian phase of control over central Asia depends upon securing pace in Afghanistan. Earlier this year, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi visited Saudi Arabia, and Iran to do just that. Both countries have been covertly funding ISIL and Taliban terrorist activities in Afghanistan, yet Wang has been able to secure trade and investment deals with both – China needs energy supplies. These however will have come with conditions attached and especially concerning covert funding. There has also been promises of much-needed infrastructure – China has already poured some US$60 billion into Pakistan’s CPEC projects, while Iran was promised US$400 billion over 25 years. Russia has also been active; Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov visiting Pakistan two weeks ago, while being a major investor in the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) that essentially provides routes from India, via Iran, through to Afghanistan, Turkey, the Caucasus, and Russia itself.

Both China and Russia have committed to ‘The Great Eurasian Partnership‘ which envisages mutual China/Russia influence extending on a region from East Asia to the borders of the European Union. At its heart lies Central Asia, a region rich in mineral resources yet until now, geographically isolated and beset with conflicts. The US withdrawal from Afghanistan allows China to continue its policy of trade development through infrastructure build, and Russia to softly reassert itself over large parts of what had previously been the Soviet Union.

A large part of securing peace and developing prosperity in Central Asia is the introduction of improved supply chains and trade routes. Afghanistan, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan are all land-locked, although Kazakhstan does have an outlet onto the Caspian Sea. It also includes Russia’s Siberia Federal District, with its highly valuable minerals, as well as China’s also landlocked Xinjiang Province. If we take the regions basic statistics as a whole and include the bordering Russian and Chinese territories, it looks like this:

Central Asia in Numbers

| Country | Population (millions) | GDP (PPP) (billions) |

| Afghanistan | 38 | 20 |

| Iran | 39 | 454 |

| Kazakhstan | 19 | 182 |

| Kyrgyzstan | 6.5 | 8.5 |

| Pakistan | 217 | 278 |

| Tajikistan | 9.5 | 8.2 |

| Turkmenistan | 6 | 41 |

| Uzbekistan | 34 | 58 |

| Siberia Federal District | 34 | 440 |

| Xinjiang Province | 25 | 213 |

| Total: | 428 | 1702 |

If taken as a total population, this Central Asian region as depicted above would be the world’s third most populous after China and India, with a GDP roughly equivalent to that of Canada. That disparity between population and wealth means there is huge potential for growth – if infrastructure can be put in place. Russia for example would benefit hugely by having Siberia better connected with Central Asia – and especially if that led to routes elsewhere.

Connecting Siberia to Asia

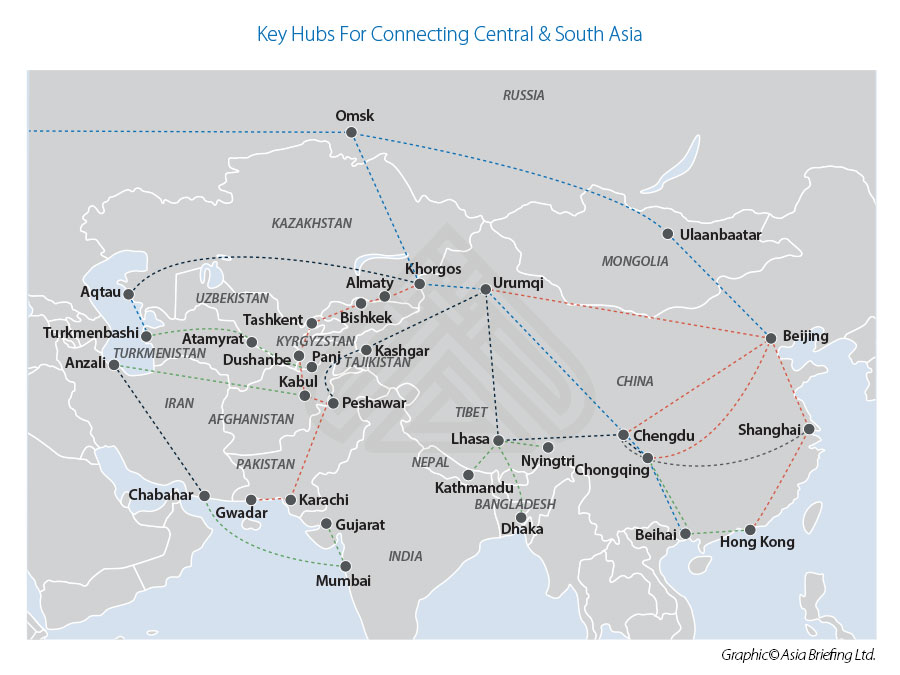

Omsk is an important rail hub and connects north and south Siberia with the Trans-Siberian routes heading to Europe as well as into Mongolia, Kazakhstan, and south to China.

Connecting Russia to Vietnam via Gansu, Qinghai, and Yunnan

Asia’s highest altitude railway tunnel was quietly completed last month, as part of the Dongshan Tunnel complex in Northwest China’s Qilian Mountains. It is expected to significantly increase traffic flow between Gansu and Qinghai, cutting more than 400 kilometers on the previous road connections and about five hours in time. To the north, this route connects through Kazakhstan and to Omsk in Siberia, to the south, with Yunnan Province to the border with Vietnam. It’s not as far-fetched as it sounds – Vietnam already has a Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union.

Connecting Xinjiang to the South China Sea

Hi-speed rail already connects Xinjiang to Beijing and Shanghai, routes heading south will connect with Chongqing and Chengdu and onto Beihai in China’s Guangxi Province and from there, through to the south-east ASEAN markets of Vietnam, Indonesia and so on. It is known as the Western Land-Maritime Corridor The Guangxi Ports will also open up China’s hinterland of some 280 million people, equivalent to seven California’s, of which about 100 million are to middle class consumer standards, yet to date have been difficult to access. It gives Xinjiang Province Sea port access for the first time.

Reconnecting Lhasa’s Sea Port Access

Old trade routes used to run between Tibet’s capital Lhasa and Calcutta and out into the Bay of Bengal and access to the Indian Ocean and South China Sea. While that is unlikely to reconnect anytime soon, China has planned rail extensions from Lhasa to Nyingtri close to Tibet’s border with India. Should there be future rapprochement between China and India, that route could connect through to the main Indian rail network. An alternative is to connect Lhasa with Dhaka Port in Bangladesh, with nearby access to Ports in Myanmar. Feasibility studies are being conducted.

Connecting Uzbekistan to the Arabian Gulf

Land-locked Uzbekistan is a rising economic star in Central Asia and has set itself on a path of reforms and compliance with international standards. It has recently signed off an agreement with Afghanistan and Pakistan to develop the Trans-Afghan Railway which would connect the capital, Tashkent, with Pakistani Ports at Gwadar and Karachi. The World Bank has agreed most of the funding. Uzbekistan is already connected by rail to Kazakhstan and Tajikistan, providing these economies also with seaport access.

Connecting China Directly to the Middle East: Kyrgyzstan’s Railway

A long-held dream along the Silk Road both old and new has been a railway that links China to Central Asia and the Middle East. Getting it done however is proving difficult: Kyrgyzstan lies in the middle. Anyone that has visited the Chinese city of Kashgar and even beyond to Taxkorgan will understand the difficulties of travelling across the Pamir Mountain ranges; huge, jagged peaks prone to shale and slate landslides in a geologically unstable region. A multimodal route already exists, using lorries to traverse Kyrgyzstan. But the real solution lies in building rail connecting West China through Kyrgyzstan and onto Uzbekistan and beyond. Currently, that route is served by rail passing through Kazakhstan’s Khorgos, but estimates show that the Kyrgyz route would save five days from the transshipment time. That prospect might not be great news for Kazakhstan, but several other countries stand to benefit from such a route if a route can traverse Kyrgyzstan. Proposed extensions would run through Afghanistan, Iran, and Turkey to Europe, while another would run through Turkmenistan and, by ferry, across the Caspian Sea to Istanbul and to Europe.

Financing the route is the issue. There are ways that China can assist. It benefits longer term as its trade through Central Asia and onto the Middle East will increase. It will win via security as well; settling down Uyghur unrest via creating wealth through trade is an on-going process. It also provides China with a third corridor West and keeps both Kazakhstan and Russia competitive. Low-interest loans are a given along BRI projects, and China can either waive or partially waive these by taking a mortgage against Kyrgyzstan’s future transit fees. Kyrgyzstan needs the increased interconnectivity a completed railway will bring, both in terms of the transit fees it can earn, and in increased trade viability of its own products. Discussions are on-going.

The International North-South Transportation Corridor: Connecting India to Russia

The International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) completes the Western section of the overall Central Asian connectivity and is designed to allow India access to regional markets – and Russia – while avoiding transport across Pakistan, with whom diplomatic and trade issues remain problematic. Its regional importance has recently been showcased as an alternative to the Suez Canal and its recent blockage.

Russia, Iran, and India have been working on the creation of this 7,200 km, multimodal trade corridor for nearly two decades, with work on the project recently accelerating amid growing trade between countries in the region, and between India and Europe. Use of the INSTC as an alternative to the Suez reduces travel times to 20 days and savings of up to 30 percent. With a spur planned to cross the Iran-Afghan border and head east to Kabul, the INSTC completes a circular route that if completed, would extend around Central Asia, offering interfaces with Russia, China, the Middle East, East Africa, to South and East Asia.

Pending Free Trade Agreements

China signed off an FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in 2018. Including Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia, the FTA is non-preferential, however tariff reduction negotiations are underway. Uzbekistan is currently an observer pending membership, while Mongolia, India and Pakistan are negotiating terms. Iran has an FTA with the EAEU as do Singapore and Vietnam. Several other ASEAN members are also looking at similar trade agreements.

Clearly, although building the connecting Central-South Asian connecting infrastructure will take time, much will be in place by the end of the decade. Once completed, the next stage in the Greater Eurasian Partnership will be drawing in the Middle East, Turkey, which is already connected via the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars (BTK) rail links and structuring trade agreements with the European Union. Brussels will see where the new trade opportunities are in these emerging markets and will be keen to sell its higher value products. That interest is already happening – the EU has granted Uzbekistan GSP+ trading privileges, going beyond standard GSP, alongside commitments to sustainable development under the arrangement. The GSP+ arrangements came into effect on 10th April; reflecting the EU’s plans to further develop ties with Central Asian economies.

Add FTA into the mix and the trade routes that once criss-crossed the Asian region in the ancient Silk Road times are highly likely to be re-energized and provide significant boosts and opportunities in intra-Asian trade, and European trade.

Related Reading

- China-Europe Rail Freight Doubles In 2020. These Are The 44 Key And Emerging European Freight Hubs To Watch

Identifying Opportunities Within the Belt and Road Initiatives

Identifying Opportunities Within the Belt and Road Initiatives

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com