The Suez Canal Alternative: The International North-South Transportation Corridor

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

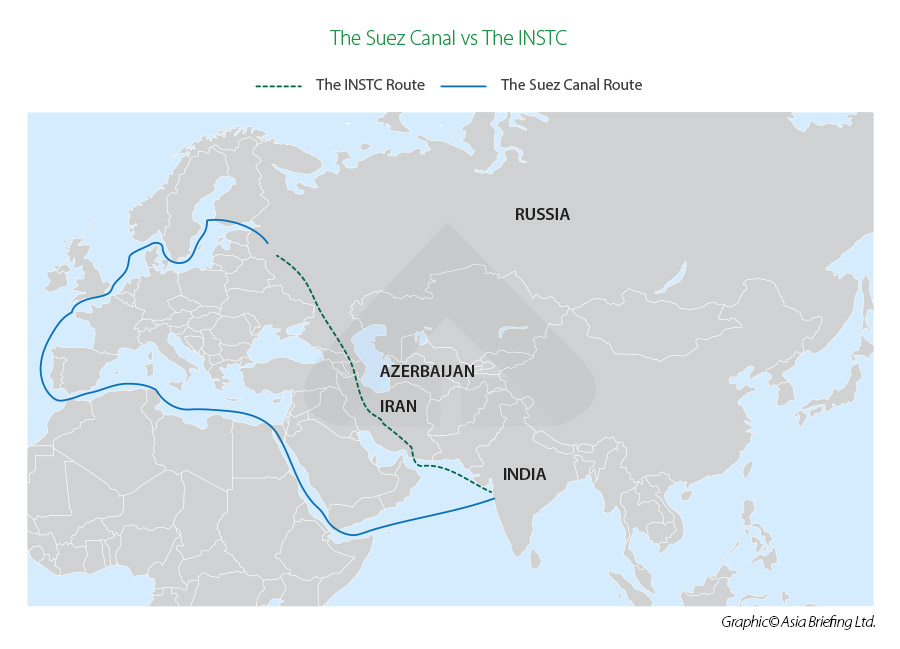

While the Suez Canal has been blocked the past week, affecting up to US$30 billion worth of goods and creating massive logistics headaches, questions are being asked about future blockage scenarios and mitigation against the worst impacts. In fact, one option is already coming onstream – the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC).

Russia, Iran, and India have been working on the creation of this 7,200 km, multimodal trade corridor for nearly two decades, with work on the project recently accelerating amid growing trade between countries in the region, and between India and Europe.

Iranian Ambassador to Russia Kazem Jalali has commented on the recent shipping mishap in the Suez Canal, suggesting that the North-South transport corridor is a great alternative to the strategic waterway that could prove both faster and less expensive. He stated over the weekend “The North-South corridor is a great option to replace the Suez Canal with a reduction in travel times to 20 days and savings of up to 30 percent.”

Jalali suggested that the recent accident in the Suez Canal, and the US$9 billion in damage to the global economy it’s causing daily, shows that “the need to speed up the completion of infrastructure and the North-South corridor as an alternative to the route through the Suez Canal has become clear and more important than ever.”

The INSTC project came into being in 2002, when the transport ministers of Russia, Iran, and India signed an agreement to create a multimodal ship, rail and road-based transport network stretching 7,200 km, from Mumbai, western India to Moscow via Iran and the Caspian Sea. Since then, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Tajikistan, Kyrgyzstan, Ukraine, Oman, and Syria have all joined the project, and new routes via Azerbaijan and Central Asian countries have been examined to eliminate the need to transfer cargoes from overland-based transport to cargo ships and back. On example is a spur heading east from the Iranian rail network to Afghanistan, allowing Indian manufacturers to ship goods to Kabul directly, and as an alternative to overland route from Pakistan’s Gwadar Port.

The INSTC corridor has been tested, and cuts current transport costs by between 30-60 percent, in addition to reducing the transit time from west India to western Russia from 40 to 20 days. Dry runs of the route carried out in 2014 and 2017 identified potential bottlenecks and confirmed cost and shipping time estimates.While the INSTC is already operational (though not as a coherent rail link), work has recently been accelerated to expand the route’s capacity, with the Russian government and business planning to invest tens of billions of rubles over the next decade. India has already committed over US$2.1 billion into the project, spending about US$500 million on the expansion of the Iranian port of Chabahar, and another US$1.6 billion on the construction of a railway line between Zahedan, southeastern Iran and the Hajigak iron and steel mining project in central Afghanistan.

This hard infrastructure is being supported by soft infrastructure. India commenced negotiations for a Free Trade Agreement with Iran two years ago. Russia has a FTA with Iran via the 2019 Iran-EAEU Free Trade Agreement while India is also negotiating a FTA with the Eurasian Economic Union.

In addition to facilitating trade between India, Iran, Russia, the South Caucasus and Central Asia, the INSTC is also seen as a prospective route for trade between India and Western Europe. An additional, currently discussed extension of the project proposes the creation of a significant canal stretching from the Caspian Sea to Iran’s southern shores, although at US$7 billion that has, until now, been deemed cost prohibitive.

If we were to imagine that this project was implemented, it would significantly alter Iran’s relations with all its northern neighbors – with the Central Asian countries and with Russia. After all, the Caspian Sea would thus be linked to international waters – an alternative trade and transport artery would appear, which would create additional regional and global trade growth potential. Given the huge losses incurred due to the Suez Canal bottleneck, the US$7 billion price tag to build a back-up may now be back on the agenda.

Related Reading

- India and Russia To Connect Supply Chains Via Iran’s INSTC

- New Russian Caspian Lagan Port To Service China, India & Iran

- Anzali Free Trade Zone: Emerging Iran’s Gateway On The Caspian Sea

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com