How China Made Inroads Into The British Commonwealth

With Barbados becoming a Republic, China is now financing a long-time British trade asset, but solutions are at hand for London

With Barbados becoming a Republic yesterday, simultaneously removing the Queen as head of state and forming its own, Barbadian legislature, the repercussions for British influence amongst its Commonwealth are rightly being questioned. This is especially pertinent to the development of China, its global trade reach and the development of its Belt and Road Initiative, and how this could sway Commonwealth political influence away from London and towards Beijing.

The fact that China has lent Barbados US$115 million to repair roads is symbolic of where assistance now comes from. London hasn’t been paying attention to Commonwealth financial support, and the political loss of Barbados is partially a result.

There is good, and bad news in all this. The good news is that Barbados effectively ran itself anyway, and that it will remain a member of the Commonwealth, although it has been allowed to leave without a trade deal in place. That would have been a pertinent parting gift.

The bad news, for the UK at least is that it lifts the veil from hiding the impoverishment of the UK in its neglect of its Commonwealth asset. That is more to do with decades of political ineptitude and disinterest than Chinese stealth. But there are tools than London can use to support its Commonwealth members, even if London is short of cash. The UK is still a significant trading power and is looking for trade deals – any deals. For example, London agreed a 6,300-product trade agreement with Uzbekistan last week. That might be good for lovers of Central Asian melons, but it’s not especially useful in maintaining Commonwealth ties. I would argue that the latter is more important.

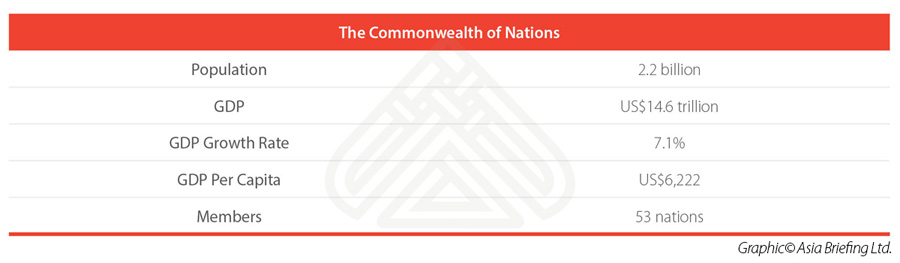

The Commonwealth is in fact a well-proven, sizable entity with a trade volume of US$14.6 trillion encompassing 53 nations. These are the simple facts:

It may surprise many that the Commonwealth has been outstripping the EU in three determinants: population size, the size of the economy, and economic growth rate.

The Commonwealth includes the following countries and territories:

Africa Botswana, Cameroon, Eswatini, Gambia, Ghana, Kenya, Lesotho, Malawi, Mozambique, Namibia, Nigeria, Rwanda, Seychelles, Sierra Leone, South Africa, Tanzania, Uganda & Zambia

Asia Australia, Bangladesh, Brunei, India, Malaysia, Mauritius, Pakistan, Papua New Guinea, Singapore & Sri Lanka

Caribbean, the Americas Antigua & Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Canada, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Jamaica, St.Kitts & Nevis, St.Lucia, St.Vincent & Grenadines & Trinidad and Tobago

Europe Cyprus, Malta

Pacific Fiji, Kiribati, Nauru, New Zealand, Samoa, Solomon Islands, Tonga, Tuvalu & Vanuatu

The British Commonwealth Is The Original Model For China’s Belt & Road Initiative

In terms of size and stature then the Commonwealth has rather a lot in common with China’s Belt & Road Initiative. That is why it is pertinent to ask what the Chinese would do with it if they were in control. After all, the Chinese economy has been growing at impressive rates for over two decades now, and at a pace far higher than the UK has managed. As I previously explained in the article The Belt & Road’s Business Secret: Cashflow Opportunities Come After Infrastructure Development the general economic consensus is that the Belt & Road Initiative will assist with development growth and opportunities in the countries in which it impacts.

As the Development Bank of Singapore has said: “The Belt & Road Initiative will help to improve infrastructure conditions in South-East Asia, enhance the overall investment environment and attract the general FDI inflows. An improvement in power supply and transportation networks, for instance, will reduce the production and logistics costs. This will, in turn, encourage Chinese (and other foreign) companies to invest and build manufacturing facilities. In addition, the infrastructure projects under BRI will create a value chain for services. This will involve not only project financing, but also engineering consultancy, engineering insurance, infrastructure management, legal, advisory, and various other types of professional services. Investment opportunities will also arise in these areas.”

So why isn’t London applying the same strategy to the Commonwealth?

Studying the modus operandi of China with the Belt & Road Initiative as a producer of investment, and the returns and increased trade this implies is of direct pertinence to the Commonwealth. How would China develop the Commonwealth if it oversaw what in the UK remains an unfashionable asset? Having studied Chinese outbound investment in a near 30-year career in China, it is apparent that the following mechanisms and trade incentives would take place were the Commonwealth a Chinese asset:

Evaluate Trade & Investment Potential & And Sign Off Tax Treaties

China has been extremely active through its diplomatic missions overseas and has built up a huge resource of trade, economic and related intelligence to allow it to make decisions as how to best prioritize countries along the Belt & Road Initiative. All are actively encouraged, but some are naturally more developed than others. The same is true of the Commonwealth. London also has the intelligence of the trade merits of each of the Commonwealth members. If China were managing the Commonwealth it would put in a concerted effort to determine which members offer the most potential in short, medium, and long term economic and trade development. Beijing would then introduce trade structures as follows:

Bilateral Investment Treaties

China has been entering into bilateral investment treaties (BITs) with other countries since the early 1980s, when the nation began its path to reforms under then-Premier Deng Xiaoping. Although many have now been superseded by more complicated and sophisticated trade agreements such as double tax treaties (DTAs) and other bilateral mechanisms, BITs remain important, especially for investors from emerging nations with relatively immature tax laws and regulatory environments. Such treaties also help to underpin the bilateral investment conditions between China and other developed nations.

The purpose of a BIT between two countries is reciprocal encouragement, promotion, and protection of investments in each other’s territories by companies based in either country. These treaties typically cover the following areas:

- Scope and definition of investment;

- Admission and establishment;

- National treatment;

- Most-favored-nation treatment;

- Fair and equitable treatment;

- Compensation in the event of expropriation or damage to the investment;

- Guarantees of free transfers of funds; and

- Dispute settlement mechanisms, both state-state and investor-state.

The sheer longevity of a given BIT goes some way to explaining their usefulness, and investors into China from other countries should be aware of the contents of these documents. China has multiple BIT in place and continues to use them in its bilateral relationships.

While BIT agreements as a rule of thumb are limited in scope, for many countries these treaties provide a useful mechanism for understanding the legal, tax and dispute resolution mechanisms for investors into the country. As such, BITs are a useful starting point to clarify legal and tax treatments under bilaterally agreed conditions and should be understood as a bilateral document of first resort when engaging with the global investment environment, in addition to the investment protection mechanisms that they offer to the respective bilateral trading partners. They also protect the rights of individuals engaging in such trade – a key point when wishing to encourage trade and investment entreprenuers both in the UK and within the Commonwealth realm.

These tend to be of particular importance for understanding the rights of companies investing from or into emerging markets throughout Asia, Africa, Latin America, and the Middle East – the Commonwealths main footprint.

China has signed off 145 BIT with other nations, while Hong Kong has an additional 20. Currently the UK has just 20 in force amongst the members of its Commonwealth, suggesting that some significant catch up needs to be deployed.

BIT for example have not been signed with, and remain pending with Gambia and Zambia. Gambia is relatively close to Europe on Africa’s West coast (it is opposite the Canary Islands) and although has a relatively small population of 2.2 million, has an average (PPP) per capita income of US$2,250. To put that into context, that is equivalent to 2/3 of the maximum annual income of a British national living on the dole in the UK. So, there is relative spending power there in a country with far lower purchasing costs and with a 200 year old history of engaging with British culture. At the last count, some 36,000 Gambians lived in the UK, with a proportion of them with the potential of acting as unofficial ‘trade ambassadors’ were they allowed to have access to bilateral trade faciitation. The Gambians are British brand aware, have English as the national language – yet there is no trade agreement. The UK is missing an opportunity to better engage by both not involving the local UK based community nor possessing the trade legislation.

Zambia meanwhile has a population of 17 million and a (PPP) per capita income of US$4,200 and also has exposure to over 100 years of British trade, investment and culture. The country itself has a population of about 40,000 ‘white’ Zambians, while the UK has a similar Zambian diaspora. That’s about 80,000 people with the potential to mobilise UK trade. Just 1% would be 800 potential individuals capable of making inroads. English is the common language. Yet again, there is no current trade agreement. Whether this is due to other factors remains unclear, yet Zambia especially seems an odd omission when the UK is prepared to enter trade deals with Uzbekistan, a country with limited UK business and cultural ties, although it is true its economy is growing and developing along well positioned structural lines. But that said, despite it having a sizeable population of 35 million, Uzbekistan is not a natural market for the UK. The culture is dominated by Central Asian, Russia and Muslim influences with little knowledge of UK brands. English is not widely spoken, meaning it is harder for UK brands to develop and position themselves in this market.

Previous British BIT entered into with India, Sierra Leone, South Africa, and Zimbabwe have been terminated. There are some fallbacks here as Zimbabwe elected to withdraw from the Commonwealth in 2003 (it has subsequently reapplied for membership) and has a UK Free Trade Agreement, as does South Africa. The UK is currently negotiating a trade deal with India, leaving just Sierra Leone out in the cold – a market of 8 million people, albeit with a low GDP per capita base of just US$500 per annum. But then again, the country had over 150 years of engaging with British culture, and again, English is the national language. There are missing opportunities there for the Sierra Leonian population in the UK – estimated to be some 21,000 – that subsequently cannot engage so easily with their own country of origin. Bilateral trade consequently dwindles at a time when every little bit would help.

Nonetheless, compared with China’s efforts, the UK is way behind China in establishing BIT with Commonwealth nations. While this is not so important when a Free Trade Agreement exists instead, BIT are of help in developing nations as they establish a modern trade platform with specific guarantees and protections – an early step towards more far-reaching agreements. They can be educational for less experienced governments and business communities in learning the rudiments of international trade. London has not been investing enough in this area as BIT codify and nurture emerging Commonwealth nations as concerns bilateral trade potential. It is a missed opportunity and one that requires resolution to prevent further deterioration.

Double Tax Agreements

Double taxation has been dubbed “one of the most visible obstacles to cross border investment,” leaving room for a significant amount of money to be saved under the almost 3,000 double taxation avoidance agreements (DTAs or DTAAs) signed between nations across the globe. To combat such obstacles, DTAs aim to prevent the same income from being taxed by two or more states, while also eliminating tax evasion and encouraging cross-border trade efficiency.

DTAs are mostly of a bilateral nature and, while DTA-signing countries are not all members of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), DTAs are generally based on model conventions developed by the OECD or (less commonly) the United Nations. And while about 75 percent of the actual words of any given DTA are identical with the words of any other DTA, the applicability and specific provisions of each treaty can vary substantially.

From an investor’s perspective, confusion about international taxation can arise when investors are subject to two different and potentially conflicting tax systems. For example, Hong Kong and Singapore adopt a “territorial source” principle of taxation, which means that only profits sourced locally are taxable. Meanwhile, other countries such as China and the United States are on the worldwide tax system, and resident enterprises can be required to pay tax on income sourced both inside and outside of the country. DTAs not only provide certainty to investors regarding their potential tax liabilities, but also act as a tool to create tax-efficient international investments.

China has signed of DTA with 85 countries along its Belt & Road Initiative as follows:

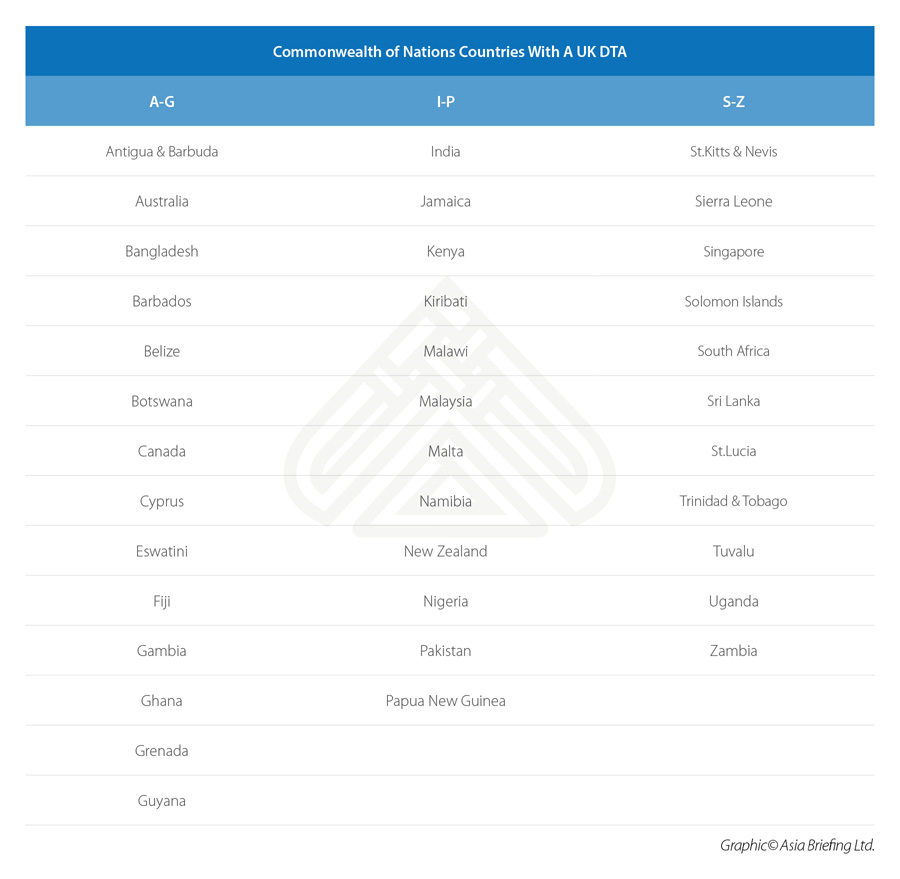

The UK has currently signed off 31 DTA with countries belonging to the Commonwealth as follows:

Free Trade Agreements

China has developed a strategic position when it comes to entering into free trade agreements – the policy of allowing dutiable and tax reduction on certain products and services being one of the main cornerstones that has projected the nation to be the world’s manufacturing hub over more recent years. Without doubt, the signing of the China-ASEAN FTA will continue to have a huge impact on China and Asia’s development in global sourcing and the foreign investment related to this. That has now received a “super-boost” with the signing of the RCEP Free Trade Agreement, which kicks in from January 1st, 2022 – just a month away – and includes not just ASEAN and China, but Australia, New Zealand, South Korea, and Japan.

China also has a Free Trade Agreement with Switzerland, which as a result has become one of the few European nations not to have a China trade surplus. From January 2022, China will have FTA with 28 countries and territories, with another 10 under negotiation.

UK FTA With The Commonwealth

The UK has currently signed off 12 ratified DTA now effective with Commonwealth nations, being Canada, Cameroon, Mauritius, Seychelles, Singapore, the six countries belonging to the SACUM (Southern African) bloc in addition to Zimbabwe. Pending and not yet in force are agreements with the CARIFORUM (Caribbean, and including Barbados) bloc, the small Pacific States (Fiji etc), and the East African nations of Comoros, Madagascar, and Zambia.

China’s Trade Take Over Of The Commonwealth Nations

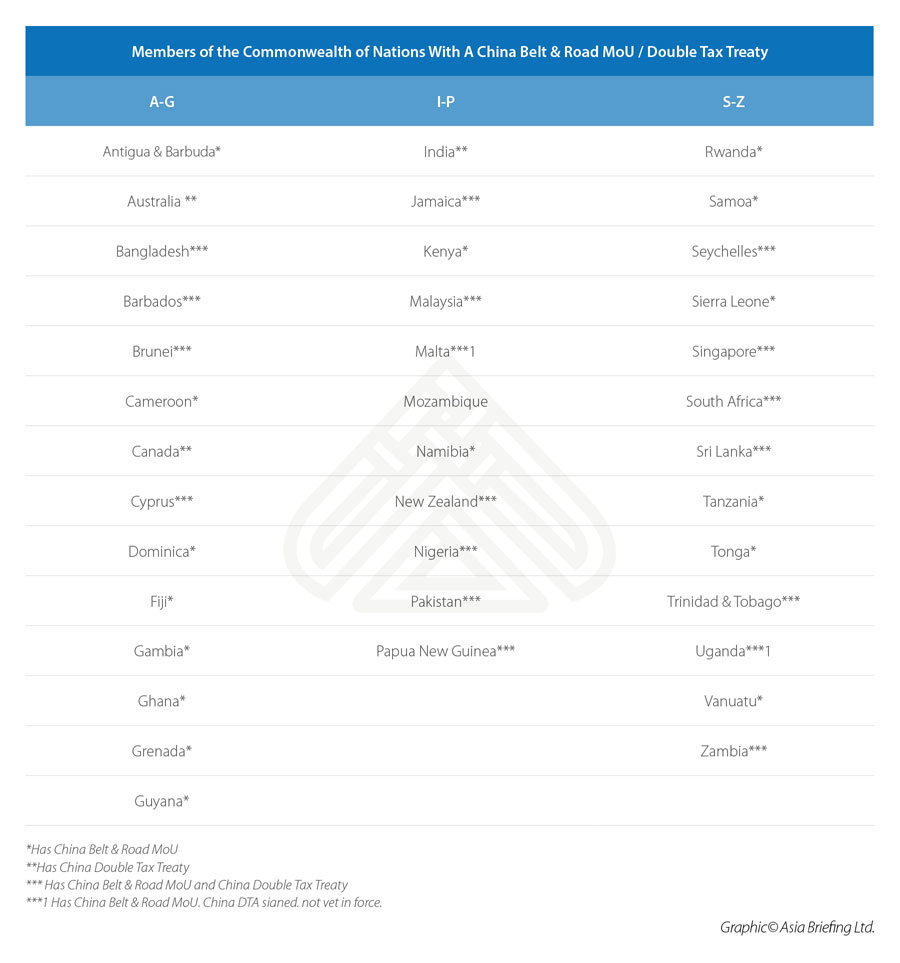

A perceived lack of effort by London in engaging with Commonwealth members has reached a tipping point with the situation with Barbados. Beijing has spotted this and has actively engaged with Commonwealth of Nations members in terms of offering them Belt & Road MoU, which often come with infrastructure developments and other investments, as well as trade benefits such as Double Tax Treaties. In doing little, or in becoming distracted, London has effectively allowed Beijing to take over the trade benefits of having the Commonwealth, and is in danger of relegating the UK to pay for an occasional state dinner at Buckingham Palace. The effect of London ignoring the Commonwealth’s trade potential has been to hand influence to Beijing. This is a list of Commonwealth Nations who now have a Belt & Road MoU and/or a Double Tax Agreement with China.

Clearly there has been a huge amount of British trade neglect when it comes to putting into place trade agreements with the Commonwealth. It is debatable whether London even understands the trade and development potential in the same way that the Chinese do. Meanwhile, it is gradually being frittered away to the benefit of Beijing.

The comparison with how China would utilize the Commonwealth if Beijing were in control is apt. With the UK now out of the EU, yet seeking trade agreements to replace it, there is a small window for it to stay calm and properly evaluate the assets it still has.

Spending time reevaluating the Commonwealth ought to be a priority. London may not have so much capital to invest, but it does have bilateral trade potential. Investing into bilateral trade in the emerging Commonwealth economies means that trade capital surpluses can then be used to repair roads, rather than have such nations instead approach Beijing for a loan.

Those BIT, DTA and FTA will assist, and efforts should be stepped up to expand their reach.

There is some capital available meanwhile, although it’s a bit too late for Barbados. The UK Foreign Secretary Liz Truss announced a new £9 billion British International Investment fund last week, meaning the tide may yet be turned to allow investment into the likes of Barbadian roads and stem off the frittering away of the UK’s only major global asset. The Commonwealth should have been positioned as a trade bloc to provide a soft landing to Brexit before that occurred, not two years later.

However, recognising this, even belatedly, and applying British initiative, trade development expertise and Belt & Road style trade agreements to the member countries of the Commonwealth, and showing them collectively and individually some commonsense trade attention, together with funding from British International Investment would be a good start.

Low Hanging Trade For UK Businesses In The Commonwealth

British businesses wanting to get ahead of the curve and start exploring – even cherry-picking parts of the emerging Commonwealth in trade development could perhaps look at the following countries with historic British brand awareness, coupled with a GDP (PPP) per capita in excess of US$5,000 and common usage of English language as a market entry tool:

| Country | British History (years) |

Population (millions) |

Per Capita GDP (US$, PPP) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bangladesh | 154 | 163 | 5,812 |

| Sri Lanka | 133 | 22 | 13,909 |

| Ghana | 83 | 31 | 8,343 |

| Botswana | 76 | 2.5 | 18,113 |

| Namibia | n/a | 2.5 | 9,542 |

| Eswatini | 65 | 1.2 | 9,168 |

| Guyana | 197 | 0.75 | 23,258 |

| Dominica | 173 | 0.08 | 9,726 |

| Tonga | 110 | 0.10 | 6,946 |

This article has been updated and revised from the article “What Would Beijing Do If It, Not London, Managed The British Commonwealth” published on July 31, 2019.

Related Reading

About Us

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists British and Foreign Investment into Asia and has 28 offices throughout China, India, the ASEAN nations and Russia. For strategic and business intelligence concerning China’s Belt & Road Initiative please email silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com