Uzbekistan – An Economic Role Model For Central Asia’s Belt & Road Initiative

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Infrastructure developments and financial reforms are positioning Uzbekistan as a Central Asian foreign investment role model

Landlocked Uzbekistan is full of the romance of the old Silk Roads, with ancient and internationally famous cities such as Samarkand, Tashkent and Bukhara all in possession of Central Asian myths, beauty, and romance. Yet while modernizing parts of the Eurasian region have proved difficult due to highly conservative traditions and hard-to-access markets, Uzbekistan has taken pages from European development overtures in additional to those of Russia and China, while remaining aloof from all, partially as it is just one of two countries worldwide that is doubly landlocked – meaning even its neighbors do not have oceanic coastlines (the other doubly landlocked country is Liechtenstein). Uzbekistan is surrounded by five countries: Kazakhstan to the north, Kyrgyzstan to the north-east, Tajikistan to the southeast, Afghanistan to the south, and Turkmenistan to the southwest.

This region also includes the Republic of Karakalpakstan, an autonomous and sovereign republic making up the entire north-west of Uzbekistan, yet with veto Governance held by Tashkent. Karakalpakstan covers an area of some 160,000 sq km and has a population of about 1.7 million with its regional capital at Nukus. Although mostly desert it does have strategic importance to Uzbekistan as to the West it interconnects with Kazakhstan and Turkmenistan road and rail to meet the Caspian sea, giving maritime access to Azerbaijan, Russia, Turkmenistan, and Iran.

From the perspective of Uzbekistan, the Belt and Road Initiative is opening the corridor to the Persian Gulf, enabling expansion of commercial and trade routes for the country. Exporting Uzbek goods to more regions is a highly attractive incentive for Uzbekistan. At the First Belt and Road Forum held in 2017 both presidents, Shavkat Mirziyoyev of Uzbekistan, and Xi Jinping of China, spoke positively of future collaboration in BRI advancement. During those meetings, the two countries signed 115 deals worth more US$23 billion on enhancing their cooperation in electrical power, oil production, chemicals, architecture, textiles, pharmaceutical engineering, transportation, infrastructure, and agriculture.

In 2019 Uzbekistan established a new government group in charge of aligning their own country’s development plan with China’s BRI ambitions. China is Uzbekistan’s largest trade partner (both in imports and exports) and has more than 1,500 Chinese businesses within its territory. In 2018, China-Uzbekistan trade surged 48.4% reaching US$6.26 billion. Uzbekistan’s main imports are machines and equipment, chemical products, food, and metals, with other important trade partners being Russia, South Korea, Germany and Kazakhstan. In terms of exports, as a producer of oil, natural gas, and gold and the world’s second largest exporter of cotton, natural resources dominate the country’s exports. Uzbekistan’s other exports include machines and equipment, and food. Uzbekistan’s main export partners are Russia, Turkey, China, Kazakhstan, and Bangladesh.

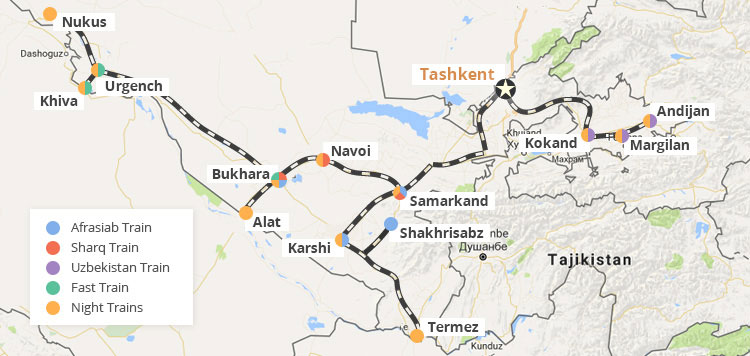

Uzbekistan is also a significant Central Asian market, with a population of some 35 million, a GDP of US$276 billion and a per capita income of slightly less than US$10,000, about the same as China but five times higher than the Indian average. This has the potential of making Uzbekistan an attractive market for south Asian exporters. Accessing Uzbekistan and linking to its own rail network however remains a work in progress, although infrastructure developments are being put in place.

The BTK Rail Connection To The Caucasus, Turkey And Europe

The Bars-Tblisi-Kars (BTK) rail link is operational for high-speed rail traffic. The route, which crosses East-West via Aqtau, Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea Port. Uzbekistan has Western rail connections with Kazakhstan running through from Karakalpakija to Beineu and onto Aqtau. From here goods are shipped to Azerbaijan’s Baku Port, traversing the Caucasus to Tbilisi, the capital of Georgia and then run south into Kars, on the Turkish border. From Kars, goods can be dispersed across Turkey, into Iran and via the Turkish rail network onto its various Black Sea Ports, providing additional connections through to markets in Ukraine, and the European Union via Constanta Port in Romania and Bulgaria’s Varna Port. The route is strategically important as it bypasses Russia and offers China an alternative southern route.

The BTK completes a transport corridor linking Azerbaijan to Turkey (and therefore Central Asia and China to Europe) by rail. In 2015, a goods train took only 15 days to travel from South Korea to Istanbul via China, Kazakhstan, Azerbaijan, and Georgia—considerably less time than by the maritime route. The line is intended to transport an initial annual volume of 6.5 million tons and 1 million passengers, rising to a long-term target of 17 million tonnes and 3 million passengers. Consequently, this links the large Turkish, Caucasian and European Union markets directly to Uzbekistan.

Uzbekistan already has free trade agreements with Azerbaijan, Georgia, and the Ukraine, and is currently in negotiations with Ankara concerning a free trade agreement with Turkey. Uzbekistan also has a preferential trade agreement with the EU that has recently been upgraded, doubling the volume of applicable items, and has agreed similar terms with the United Kingdom.

The International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC)

The INSTC is a multi-modal route running from India’s largest port in Mumbai, via shipping to the southern Iranian port of Chabahar. From there, containers are placed onto road and rail and distributed north to the Iranian port of Anzali, on the Caspian Sea, reloaded onto ships and distributed to ports in Azerbaijan from which they can reconnect with the BTK rail line through to Georgia, Turkey, and Black Sea ports to Europe, north to Russia and northeast to Turkmenistan and Kazakhstan. It sounds complicated – yet using this route is less costly and quicker than the Suez canal route to these same destinations. Of interest to Uzbekistan is an INSTC spur, the Trans-Caspian railway, heading east from Iran and into Turkmenistan, which connects with the Uzbek railway network from the border cities at Turkmenabad and Urgench in Uzbekistan.

The Trans-Afghan Railway

This route was agreed last year between the governments of Uzbekistan, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, and would see the building of a 573-kilometer route from Mazar-e-Sharif to Peshawar, via Kabul. The project, at an estimated cost of US$5 billion, will provide access for Uzbekistan to Pakistani seaports on the Arabian Gulf. It is part of the Quadrilateral Traffic in Transit Agreement (QTTA) which also links to the China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC). In Uzbekistan, the deal has been called the “event of the century” by Tanzila Narbaeva, the Chairman of the National Senate, noting it as “another example of Uzbekistan actively pursuing an open and pragmatic foreign policy.”

The China-Ferghana Valley Railway

This route would connect east with Kyrgyzstan through an existing rail line connecting Uzbekistan’s Andijan to Osh in Kyrgyzstan. That is operational, however the bigger picture is the much-discussed potential for a Ferghana Valley railway that would bisect Kyrgyzstan with connections north to Almaty in Kazakhstan, which is already linked to China with high-speed connections to Urumqi, the capital city of Xinjiang Province, and Chinas national rail network.

A southern route would cross Kyrgyzstan and enter China at the Erkeshtam border crossing, near to Kashgar. In time, that could possibly connect south to another proposed railway running from Kashgar to Gilgit in Pakistan, joining Pakistan’s national rail network and again through to Ports on the Arabian Sea.

These projects are expensive, and have been hampered by both the cost, political shenanigans, and the sheer engineering challenges. However, the political situation in Kyrgyzstan appears now to be settling, and a pragmatic, less egoistic President now in power. If financing can be found, this route is more likely than not to happen.

New Economic Transparency & Investor-Friendly Reforms

It is not just potential new rail connectivity that is driving contemporary Uzbekistan forward. It has adopted a more transparent method of governance and been following international protocols and financial reforms, making it a Central Asian darling of the West. Nor is it reliant on China for infrastructure financing, it has been adopting PPP models to develop toll roads and other infrastructure projects including banking and finance. This has attracted international investors who are also being welcomed into Uzbekistan’s banking and financial services industry, atypical for Central Asian nations.

These changes have been wrought since 2016, when the previous Presidential incumbent, the Soviet hardliner Islam Karimov passed away. I had been a (now funny, but not at the time) victim of Uzbekistan’s difficult policies before then, when applying for a visa to visit my then local girlfriend Gulia in Tashkent, my visa application from the Uzbek Embassy in Singapore was constantly delayed. That application had to be accompanied by an expensive, and non-refundable return business class airline ticket, in addition to pre-paid accommodation and transport, travel insurance, details of my bank accounts and a detailed itinerary. Everything was checked, Gulia having to field phone calls and even a visit about who was coming to stay. I was becoming increasingly frantic as my visa remained unissued until the day of departure. Finally, I got a phone call “Good news! Your visa is issued!” But it was too late, my plane was due to depart in 2 hours and I still had to get to the Embassy to pick up the visa and check in. It was a quite deliberate ploy and cost me a fortune – and the girl.

My travails illustrate old Uzbekistan. Today’s Uzbekistan, just five years later, is totally different, innovative, and business investor friendly. Uzbekistan offers visa-free access to many nationals, while taxes such as VAT have been reduced to 15% as the country begins to introduce financial and tax reform to encourage trade. That has encouraged the EU, who have agreed a GSP+ programme with Uzbekistan designed to reduce tariffs on Uzbek exports and EU imports. Carrefour have heard that and set up their first stores in Central Asia as a result. Other investors should be doing the same.

Although much still must be done to allow easier access East, the Caspian and INSTC routes are already operational, giving access to Uzbekistan from the West and India. These possess significant markets, a fact also not lost on post-Brexit Britain who has signed off a trade agreement with Tashkent, the first with a Central Asian nation.

There are additional trade developments in hand. Uzbekistan has recently joined the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) as an observer nation and has signaled intent to join. That will require some reforms on the EAEU part, and especially in customs regulations, which remain awkward and require attention. The EAEU comprises Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia and would give Uzbekistan free trade access to these markets. If it were to join as a full member rather than negotiate an FTA, that would also open the FTA that the EAEU has with Iran, Singapore, and Vietnam. There are more to come – China is negotiating tariff reductions on trade with the EAEU while India, Egypt and several ASEAN nations are also discussing free trade. These will significantly enhance the ability to access Uzbekistan’s market while at the same time provide huge incentives for its exporters.

Market research and legalities still must be understood of course; we are able through our various legal and tax networks to introduce experienced on-the-ground intelligence in these areas to would be investors. Longer term, the hope is that the Uzbekistan experience of opening and reform will spread across the rest of Central Asia and provide new market opportunities. Uzbekistan is certainly a good place to start the process.

Related Reading

- Kyrgyzstan And The Belt & Road Initiative: Trans Central Asian Road & Rail Connectivity & Added Value Manufacturing Services

- Kazakhstan: The Belt & Road Highway To Europe & Central Asia

- Turkmenistan: Gradually Opening To The World Via Belt & Road Trade

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com