The Belt and Road Initiatives Soft Power Strategy: Global Tax & Trade Reform

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China this year has placed its Belt and Road Initiative at the very heart of its Foreign Policy in updating its Foreign Aid Programme, re-stating it is a core pillar of its foreign trade for 2021.

This comes after years of media criticism about China’s intentions, mostly concerning the imposition of debt traps and sovereignty issues riding over the trade benefits that the infrastructure build has given. These can now be discounted, with venerable institutions such as Chatham House stating that there was in fact, no evidence of debt trap burdens being placed on other nations because of China’s lending.

China has signed off the recent Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) agreement, which includes all ten ASEAN nations as well as Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea. This brings benefits to foreign investors in China, an issue we discussed in the article RCEP FTA Signed, What Can Foreign Investors in China Expect?

ASEAN includes Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, Philippines, Singapore, Thailand and Vietnam.

ASEAN’s collective GDP in 2019 was about US$9.34 trillion, and is a market of about 135 million middle class consumers (24% of the total population). This is expected to double in size in the next decade, and is one of the global trade development drivers. ASEAN nations meanwhile, apart from enjoying Free Trade amongst themselves, also have Free Trade Agreements in place with China, India, Australia, New Zealand, Japan, and South Korea.

While Singapore is a wealthy market and a prime position for global financial services and products, acting as the de facto financial capital for ASEAN, the Vietnam market now provides opportunities for manufacturing companies who may wish to have an alternative to China, and especially in export manufacturing to service China itself, India, the other ASEAN nations, and now the EU. Vietnam signed off an Agreement with the European Union which came into effect from August 1 last year.

Russia like China has diminished in global political stature in recent years, but that doesn’t mean to say it is totally off limits, and it remains a significant market in its own right. Sanctions mostly affect either specific individuals or Russia’s Oil & Gas sector, while Russia is itself the lead nation of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), which also includes Armenia, Belarus, Kazakhstan, and Kyrgyzstan. Collectively, the EAEU is a market of about 176 million people with a combined GDP of about US$5 trillion.

What is interesting about the EAEU is that it has Free Trade Agreements with Singapore and Vietnam, in addition to Serbia, Iran and China. The latter is currently non-preferential; however, tariff negotiations are underway with progress expected during 2021. Russia-China trade is expected to double from now to 2024, hitting about US$200 billion. The EAEU is also currently negotiating an FTA with India, with signs that this is also expected to be completed this year. Russia’s proximity to China should also be of interest; a subject I explored in the article Opportunities For Businesses In the Russian Far East.

The Belt & Roads Developing Tax Incentives For Trade

The reason why I illustrate the situations between China and ASEAN and Russia is because although the Belt & Road Initiative is often regarded as an infrastructure ploy, is that it is additionally supported by tax and trade incentives. In the case of ASEAN, the recent RCEP deal adds additional detail to China’s existing Free Trade Agreement with ASEAN, which came into effect a decade earlier. In Russia’s case, we are likely to see tariff reductions included in negotiations between China and the Eurasian Economic Union. We can also point to the behavior of China when it comes to Africa.

China was instrumental in putting together and encouraging the African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) which entered into force on January 1 this year. That deal unites a US$3.4 trillion market and eliminates tariffs on 90% of all goods traded within it – a massive boom for African sourcing and consolidation.

But China has laid groundwork elsewhere too, in signing off a Free Trade Agreement with Mauritius that came into effect the same day as AfCFTA. Mauritius has long been a quasi offshore financial and trade services consolidation island off the East African coast and is itself part of AfCFTA. China has suddenly added an African version of Hong Kong into the mix.

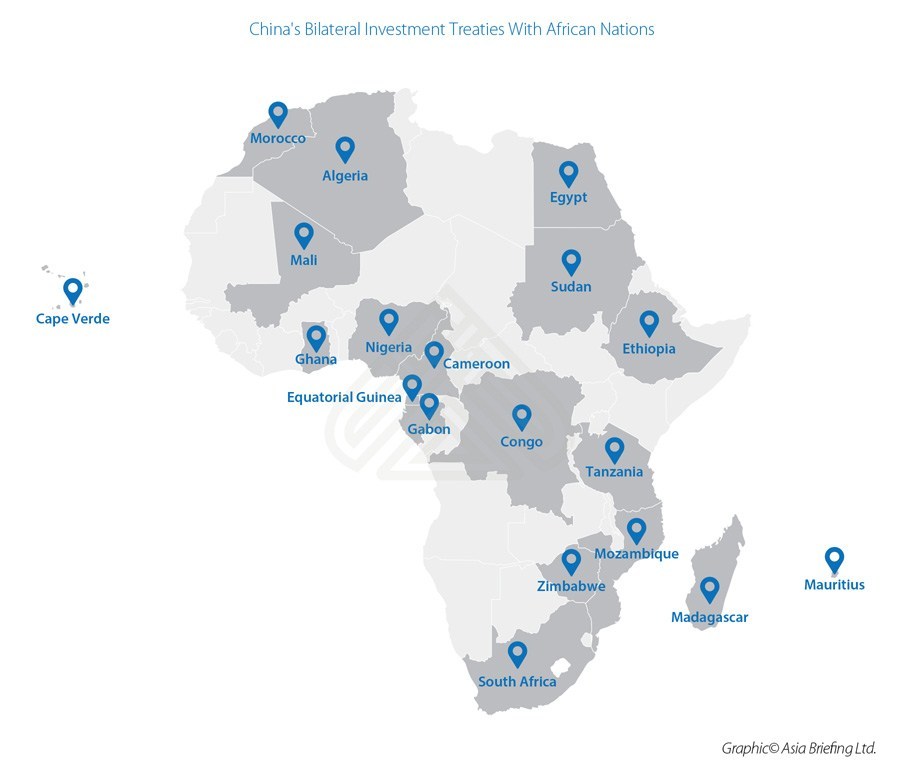

Then there are China’s inroads with additional African Treaties, Double Tax Agreements and even building of Special Economic Zones. Take a look at the maps below:

These structures are also being put in place across the Belt and Road Initiative. I previously discussed China’s Free Trade Agreements Along The Belt & Road Initiative China’s Free Trade Agreements Along The Maritime Silk Road and Free Trade Zones Linking China, Russia and Europe .

Russia too, is building its own Free Trade structures across Africa and Asia, has a huge network of them stretching across Russia from China to Europe and has the Trans-Siberian rail infrastructure to deliver along those routes.

It is clear that the soft power that is being developed along the Belt and Road Initiative is also being put in place and is concentrating of a new era of reduced tariffs and taxes while also putting in place investment incentives. Sri Lanka’s Free Trade Zone at Hambantota is offering profits tax at zero rates for ten years to secure foreign investment. It is a similar story in many other areas too – from Pakistan and Iran through to Hainan and Karnataka where Elon Musk’s Tesla are busy installing a factory for manufacturing electric vehicles.

This explosion of Free Trade Zones, Free Trade Agreements and Tax Incentives are another, soft power example of China’s trade and manufacturing exports – China itself began these very same policies when it began its own opening up and development back in the late 1980’s. We have all seen what has happened since.

A New China For Investors In 2021

A common question I am often asked these days concerns the Chinese slowdown of overseas financing of the BRI. To which there is a very simple explanation: it’s nearly finished. China’s ODI and foreign policy for 2021 have in fact already been laid out in statements made by Xi Jinping at the recent United Nations summit , by Foreign Minister Wang Yi at the recent Belt & Road Forum and by new Minister of Commerce Wang Wentao at the recent Central Economic Work Conference. All quite clearly state China’s intentions: to focus ODI on more strategic investments, such as healthcare and technology, to take more strategic positions within foreign companies in specific sectors, including minority positions, and to rebalance the Chinese economy by moving it to away from manufacturing to a consumer base.

China spent US$4 trillion on BRI infrastructure – that part of the investment is nearing completion. China has also followed this up by making three strategic changes, introducing a revised foreign investment law last year, relaxing foreign investment in various industry sectors, and introducing a new ‘dual circulation strategy’ designed to spur consumer demand. I summarized these recently in the article A New China For 2021.

It is an irony that the political situation between Washington, London and Beijing has deteriorated at the same moment that China market access – and increasingly along the Belt & Road Initiative – is been the best it has ever been.

However, there are many good reasons why global companies should continue to look to China, both the growing consumer market, and access to an extensive Free Trade Agreement Network.

Exploiting The Belt & Road Initiative

Foreign involvement in Belt and Road projects has been limited, as much of the interest and attention has been on participating in the multi-million-dollar infrastructure builds, and these typically come with Chinese state financing, conditional that Chinese SOEs conduct the work. Chinese BRI projects favor other State-Owned partners rather than public companies, both for business cultural reasons and for keeping details out of public scrutiny; while the sheer nature of Chinese financial competitiveness combined with sometimes superior technology and construction expertise, also plays a part, especially on difficult terrain. China for example built the rail to Lhasa, very few if any foreign contractors have that type of experience.

Accordingly, involvement in BRI projects tends to be limited to Chinese contractors and their local partners where the project is situated. In fact, other foreign investors are missing a trick here, as most of China’s BRI projects are now nearing completion with the infrastructure build coming to fruition.

This creates new opportunities for foreign investors to look at the original purpose of building the project in the first place and the increased commercial business flows this will generate. For example, Sri Lanka’s Southern Expressway was completely Chinese built and financed (with a lot of criticism about the cost). However, that spurred a huge growth in the regional tourism industry. I touched on that project here and about the related Colombo Port City development here which will see Colombo city develop into a Southeast Asian office center for back-office functions. All of these provide investment and service development opportunities for foreign investors.

The message here is that the opportunities lie where the BRI infrastructure build has been completed, there are asset enhancements and appreciations, as well as tax and trade incentives.

International investors can provide the service elements to support the increased trade and human needs the physical infrastructure provides. But very few businesses are looking at this, the penny hasn’t yet dropped, yet there are ways to examine the potential for involvement and exploiting the build.

While the immediate momentum, scale and long-term timeline driving BRI projects has slowed due to the Covid-19 pandemic, Multinationals will increasingly want to take advantage of China’s more pragmatic view on international involvement and constrained ability to be the sole financier of all things BRI. There may have been a slowing of BRI investment right now, but the new trade routes are here to stay. China judges the short term by decades, and the BRI is an opportunity for businesses with a longer-term development view. International companies and investors have plenty to consider.

lt is time to re-evaluate the potential, the wide ranging, multi-lateral connections, new supply chains and tax incentives, and assess where international investment potential really lies.

Related Reading

- Belt & Road Trade 30% Of China’s Total During H1 2020

- China’s 2021 Progress Across The African Belt & Road Initiative

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com