Has China’s Belt and Road Initiative Shifted the Geo-Political Regional Debate from APAC to the Indo-Pacific?

Op/Ed by Andre Wheeler

So, what is in a name? Is it merely symptomatic of a diversionary tactic or is it emblematic of a greater understanding of the “middle kingdom” after years of obfuscation? Responses to this geographic descriptor change reflects the ideological stance of the respective parties. China would prefer a continuation of the use of APAC – referring to the ‘Asia-Pacific’ as it confines the narrative to the United States’ western pacific dominance. It is however interesting to note that the narrative and use of terms in the current geo-political spectrum is undergoing a fundamental shift. This is partly driven by China’s increasingly assertive approach to diplomacy but also the intent of China’s trading partners to deal with an over reliance on Chinese markets as they work to realign their supply chains. There is an attempt to realign strategic partnerships without being a target to be “influenced” by an upset Chinese Communist Party. In a way, political correctness is taking on a fluidity akin to wrestling with an octopus coated in olive oil.

In the emerging narrative there has been a shift to the softer claim of supply chain diversification as opposed to the more aggressively framed decoupling call. This softer language has greater cut through with the Chinese domestic market as it incorporates a “win-win” engagement as opposed to the “win-lose” position suggested under a decoupling narrative. Strategically this nuanced change helps Xi Jinping in adopting a less assertive approach as he does not have to be seen take strong action to restore Chinese Pride because of a perceived external threat. Consider the difference in approach and response by China with regards Germany (a diversification school) and Australia (a decoupling narrative).

Why does a shift from the Asia-Pacific to the Indo–Pacific narrative signal a crossroads in China’s international engagement?

Whilst both terms have been around for centuries, there has been a greater scrutiny of these descriptors in recent times. Essentially the shift towards an Indo–Pacific analysis from the previous dominant focus on the Asia–Pacific trading region signals a greater understanding of the shift currently taking place in global trade. A new super-economic zone has emerged as the global order shifts from the Asia-Pacific trade axis.

This shift has implications for China’s leadership and Xi Jinping, particularly in their engagement with the Chinese internal domestic market. Essentially the description of the APAC region made it was easy for them to frame the USA as the enemy. It enabled the galvanization of the Chinese internal civil society around an easily defined existential threat. Furthermore, it contains the debate to a narrow economic threat that is separated by the vast seas of the Pacific Ocean. Furthermore, it was consistent with China’s ongoing public utterances that their ambitions did not want to challenge the existing global order.

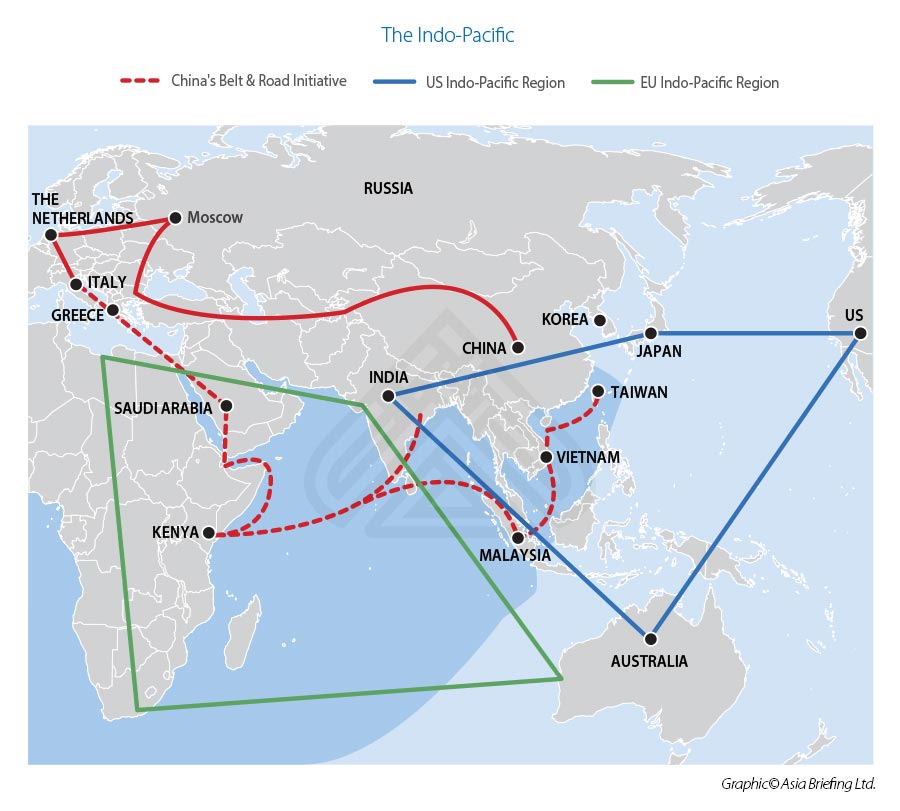

With the exponential economic growth and increasing influence of China over the last decade, China has come to be seen that China is the only great power that threatens the status of the United States. With the Belt and Road Initiative connecting Asia and Europe, China can be seen as a revisionist power that is stiving for regional hegemony in the Eurasian trading zone. As such, this has transformed the debate from regional outcomes to a concern for a new global economic order. Issues are translating from regional specific issues to global impacts. It explains why issues such as Huawei’s 5G starting as USA based cyberspace concern now occupy much of Europe. The map below helps visualize the transformation.

An interesting narrative has emerged from the current USA-China geopolitical tensions and a greater understanding of how the BRI has changed the trade debate. Western aligned economies are more inclined now to refer to the Indo-Pacific as a descriptor as opposed to APAC. It is seen as a more accurate description, as illustrated above.

The map also highlights a key vulnerability for China, namely the maritime choke point in the region of overlap between the Indo–Pacific strategy and the BRI. One of the main drivers for the BRI was to enable China to keep its maritime routes secure and find a means by which it could bypass the likes of the Malacca Straits. Whilst the BRI opened trade to its east, it explains China’s South China Sea engagement in creating an outer island protection zone from potential disruption of their regional maritime trade ambitions. This outer island protection zone extends from Taiwan, Philippines, and western Malaysia /Brunei, highlighting why the likes of the emerging conflict over China’s claims to Taiwan is becoming problematic.

With the unravelling of trade dependence brought on by COVID-19 and the disruption of BRI supply chains, the EU now sees China not as a strategic partner, but as a competitor. This has been exacerbated by the South China Sea activity and the softening of acceptance of Taiwan as an independent state.

The net result is a movement within the major economies of Europe to build an EU wide strategy and approach to the Indo-pacific. France recently created the new position of ambassador to Indo-pacific to counteract CCP growing influence in the region. Based in Paris, the ambassador’s role is to co-ordinate diplomatic activity in the region. With France having placed US$176 billion of FDI in the region, they now define the new trade area of the Indo-Pacific as being the coast of Africa to West Australia’s Coral sea, driven by an economic gravity shift from the Atlantic to the Pacific.

Germany has also moved from shaping its Asian strategy around China and announced it will now focus on building stronger relationships with the likes of Japan, Korea, India, and Vietnam. It hopes to have a comprehensive Indo-Pacific strategy in place by 2022. The aims of this strategy is to diversify their trade by increasing FDI and trade outside of China and to other countries more aligned to their philosophy on democratic institutions based on rules and cooperation and not the law of the strong and powerful. They set their first Indo-Pacific guidelines in September this year with a focus on inclusivity, wanting to carve out a more active role for the EU in the East, including the East Asia Summit. They call the approach diversifying as opposed to decoupling from China, particularly as they address cybersecurity concerns

What is also clear is that the evolving Indo–Pacific analyses have turned attention to preserving economic relations with China through a range of targeted mitigation measures and realigning the relationship. Just as China has a “White List” that determines what industries are open to FDI, the EU is developing its own “Green List”. This will identify what industries are “safe” and those that would require mitigation measures. Essentially, industries that pose security risks are not on the “green list” of safe investments. This analysis reveals that 46% of current Chinese FDI into Europe do not make it onto the green list as these have a deemed risk around sensitive individual data, strategic infrastructure, and digital intellectual property. Interestingly, just over 80% of EU investment into China is regarded as benign, highlighting an imbalance in trade profile.

So, what’s in a name?

Whilst China would like to retain focus on the APAC, the Belt and Road Initiative has reshaped the conversation by others to look through the lens of the Indo-Pacific. It has manipulated the conversation from being one of a regional discussion to one that has a global reach. Perhaps we are witnessing an unintended geo-political consequence of the Belt and Road Initiative, with the Indo-Pacific label showcasing the real intent of China.

We are grateful to Andre Wheeler of Wheeler Management Consulting for contributing this commentary. Please contact him via linkedin.com/in/andre-wheeler-7a9a1a23 or via email at andre@wheelermanagement.com.au

Related Reading

- After The Coronavirus: The Asian Belt & Road Initiative Economic Recovery 2020-2021

- Political & Trade Uncertainty Looms In The EU & USA – But Asia And The Belt & Road Initiative Are Looking Good

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com