China Targets, Funds, and Incentivizes Eastern Europe as Bilateral Trade Potential Intensifies

China has begun offering incentives to members of the “16+1” Eastern European trade group, which was formed in 2012. It is launching a new investment fund and looking at bilateral trade agreements tailored specifically to each countries’ demographics, with wide reaching implications for China-EU trade.

China has begun offering incentives to members of the “16+1” Eastern European trade group, which was formed in 2012. It is launching a new investment fund and looking at bilateral trade agreements tailored specifically to each countries’ demographics, with wide reaching implications for China-EU trade.

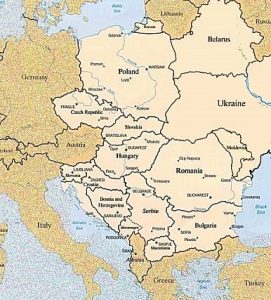

The grouping, officially known as the Cooperation between China and Central and Eastern Europe (CEEC), includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia as the 16 Eastern European nations, plus China.

CEEC European Nations by GDP and Population

| Country | Population (millions) | Annual GDP (US$, Billions) |

|---|---|---|

| Albania | 3 | 11.5 |

| Bosnia & Herzegovenia | 4 | 17 |

| Bulgaria | 7 | 51 |

| Croatia | 4 | 56 |

| Czech Republic | 10.5 | 190 |

| Estonia | 1.5 | 23 |

| Hungary | 10 | 125 |

| Latvia | 2 | 48 |

| Lithuania | 3 | 41 |

| Macedonia | 2 | 11 |

| Montenegro | 0.6 | 4 |

| Poland | 38 | 489 |

| Romania | 20 | 170 |

| Serbia | 7 | 37 |

| Slovakia | 5.5 | 86 |

| Slovenia | 2 | 43 |

| Total (rounded up): | 140 | 1.4 trillion |

If the European CEEC countries collective GDP were compared to other nations, it would be the eleventh largest global economy.

The CEEC nations are important to China as a Gateway to Europe, as they possess both the ability to access the European Union as well as provide sought-after logistical support in dealing from cross border standards engaged in Russia and elsewhere, such as railway gauges. It is not a tariff or trade based union, as 11 of the 16 nations are members of the European Union and trade protocols need to be directed via Brussels. However, what it does do is unite the 16 nations and China into a forum for discussing issues such as logistics and services.

This is key to both China and the EU, and Russia in a future post sanctions world as rail connections to the EU almost all pass through Russian built and standardized rail links through Russia itself, Belarus, and the Ukraine. While difficulties in the latter prevent it being currently utilized as a bridge, border nations such as Estonia, Lithuania, Latvia, and especially Poland (the largest member of the grouping) can provide this, although in all cases investment is required to upgrade and improve services. Other countries such as Bulgaria and Romania still possess a certain nostalgia and infrastructure based upon their Soviet years, although their own internal leaders of the time remain largely despised, meaning that these nations are pragmatic when it comes to Moscow and open enough to consider ideas that encompass a more pro-active border trade. Many of these nations still enjoy a large and valuable amount of tourism trade with Russia, a fact not lost on the current need to upgrade cross-border services.

China’s role has been to allow the 16 platform to discuss upgrading infrastructure from the Soviet period and to discuss redevelopment of border controls, routes, and the initiatives required to upgrade these countries, not just with developing their ties to Western Europe but also making sure these developments are China-friendly and fit in with China’s own development and trade plans.

To this end, China and the CEEC nations quietly launched a €50 Billion development fund last year. The China-Central Eastern Europe Fund is run by Sino-CEE Financial Holdings Ltd, a company established by the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC). The fund is projected to raise 50 billion euros in project finance for sectors such as infrastructure, high-tech manufacturing and consumer goods, in accordance with market demands, according to the ICBC. To date it has raised money and invested in fairly weighty projects in Poland, Bulgaria, Hungary and the Czech Republic. Curiously the investments have not been specifically infrastructure related, and have been directed at solar energy and even business investments to date, suggesting that the onus thus far is on political sweeteners rather than infrastructure development. The EU, an observer to these discussions, is also somewhat nervous about the situation as it does not allow it a direct voice in how China is encouraging developments on the eastern edges of its own borders.

The difficultly that China has in dealing with such countries is that while collectively they may be an impressive grouping, individually some of these nations have populations and GDP far lower than many average Chinese cities. Yet political protocol demands sovereign respect; an expensive exercise in China and the smaller Eastern European nations. Many of the latter simply do not have the resources to properly examine China potential. Accordingly, China has progressively been utilizing the auspices of the National Reform & Development Commission. (NDRC) to examine bilateral ways forward instead of putting more strain on the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Ministry of Commerce, thus negotiating around its own political structure, those of 16, and allowing Ministers on both sides to effectively delegate research work elsewhere within Government without having to further strain primary diplomatic resources in the respective foreign and commercial Ministeries.

The NDRC is a research institute, with vast resources and direct ties to China’s leadership, headed up by the Chinese President. Yet free of Ministerial protocols it is better placed to deal with smaller nations, and has been actively involved in making suggestions, including the drafting of bilateral agreements for negotiation with smaller countries, including some of the Eastern European 16, a new political move by China.

This is a shrewd gambit, freeing up time and energy, and diplomatic protocols while permitting either party to get on with business as usual. The NDRC, fed by local market intelligence provided by each respective Chinese Embassy, is then able to pinpoint areas of interest for China to invest in or support. When restricted to trade and commerce, this is benign, and can create opportunities for the smaller and border Eastern European countries who may be aware of the issues they face but may not have the resources to develop them. In this case, China is essentially acting as a distant Uncle, encouraging smaller relatives how to develop.

In this regard, Eastern Europe has much to offer China, and especially in services provision. While the intellectual fear among many in Europe would be local markets flooded with cheap Chinese goods and pressure being placed on ineffective domestic manufacturers, China has quickly grown wise to the fact that not all its exports are especially beneficial when larger prizes are at hand. China wants market access, but not at the price of destroying local economies. The benefit that Eastern Europe has is it acts as a border to be crossed by China to access the wealthier markets of the Western EU. China is also experiencing middle class growth. Increasing numbers of Chinese nationals have increasing amounts of disposable income, as any European will appreciate when just walking the streets of their home cities – those same Chinese tourists visiting sights, staying in hotels and making en mass restaurant reservations are the same people back in China who will be demanding imported European goods. By 2022, five years from now, McKinsey estimate 550 million Chinese nationals will be middle class citizens.

This is a huge opportunity for Europe, and Eastern Europe in particular when it comes to services provision. Smaller countries such as Estonia have already made huge strides in the development of e-commerce and the nation is already one of the best connected in Europe. That initiative extends to Tallinn’s regional airport now handling 5% of all China Post packages via Estonia’s e-commerce platform. It is able to process, track and synchronize the logistics necessary to get European sourced parcels through to China. Alibaba are a huge player in the Estonian business community and using the digital resources Estonia has is capable of transforming the Estonian economy. It is already investing and has specific plans to extend its Estonian base as a logistics hub for servicing the rest of the EU. To this end, China and several CEEC countries are currently re-negotiating their outdated bilateral investment treaties. Their replacements can be expected to be heavily influenced by contemporary business trends and regional initiatives such as e-trade, block chain and Fintech, especially if the NDRC are involved in structuring them. Contents are yet to be disclosed but it can be expected to be an interesting pointer as to how China views and can provide solutions to smaller national interests and developments among European nations. I suspect that the documents, when available, will usher in a new platform of regionally planned out, yet bilaterally independent trade facilitation and investment that will enable Eastern Europe to develop and to allow the Chinese access but in a manner both able to benefit China’s own industries, yet sympathetic to and advantageous to local European national concerns and existing infrastructure, especially if hi-tech. The evidence for this more magnanimous Chinese investment approach is in fact already there.

Estonia is just one example but a harbringer of how China’s development is impacting upon Eastern Europe, and how the region can position itself as a service centre for Chinese commerce, both in digital technological platforms such as those already provided by Estonia, or hardcore services such as freight forwarding, warehousing, re-packaging, consolidation and transportation logistics in a bilateral, two way trade avenue from .East to West. Bulgaria is another example of Chinese infrastructure investment, with a €20 million investment being made in Bulgaria’s Burgas Port on the Black Sea. and an additional agreement to finance a Free Trade Zone development in Trakia. There are many other examples; Bosnia & Herzegovnia’s Power Plant at Stanari, investments in Croatian electric automotive company Rimac and similar auto investments in Romania. Those fit in exactly with Chinese owned Volvo’s plans – they have just announced the brand will only produce electric vehicles from 2019. The European production facilities and technologies are already in place.

China is also investing in solar energy and real estate in Romania, provided a €1.5 billion loan to Hungary to allow regional budget airline Wizz Air to purchase eleven Airbus, and has invested in the Huawei Academy, which aims to promote education involving communications technology in Hungary.

There are many other examples. It is a useful pointer however to note that these are not problematic investments designed to flood Europe with cheap goods. Instead, they are well thought out, locally sympathetic and regionally enhancing. Eastern Europe is at the forefront of this Chinese wave of OBOR investment into the EU. If the members of the CEEC 16 can get their individual strategic development plans on the right footing, the future for each of their specific economies could be very bright indeed.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner and Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates, with over 25 years of assisting European companies in the Chinese markets. The firm are members of the European Chamber of Commerce in China and have facilitated several billion euros worth of EU-China investments over the years. For further assistance with strategic assistance in engaging with China, please contact the firm at china@dezshira.com or visit the firms website at www.dezshira.com

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is published by Asia Briefing, a subsidiary of Dezan Shira & Associates. We produce material for foreign investors throughout Eurasia, including ASEAN, China, India, Indonesia, Russia & Vietnam. For editorial matters please contact us here and for a complimentary subscription to our products, please click here.

Dezan Shira & Associates provide business intelligence, due diligence, legal, tax and advisory services throughout the Asian and Eurasian region. We maintain offices throughout China, South-East Asia, India and Russia. For assistance with OBOR issues or investments into any of the featured countries, please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

Related Reading:

Related Reading:

An Introduction to Doing Business in China 2017

Doing Business in China 2017 is designed to introduce the fundamentals of investing in China. Compiled by the professionals at Dezan Shira & Associates in January 2017, this comprehensive guide is ideal not only for businesses looking to enter the Chinese market, but also for companies who already have a presence here and want to keep up-to-date with the most recent and relevant policy changes.

China Investment Roadmap: the e-Commerce Industry

In this edition of China Briefing magazine, we present a roadmap for investing in China’s e-commerce industry. We provide a consumer analysis of the Chinese market, take a look at the main industry players, and examine the various investment models that are available to foreign companies. Finally, we discuss one of the most crucial due diligence issues that underpins e-commerce in China: ensuring brand protection.

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.