Turkish Government Approves Canal Istanbul Project

- Would connect the Marmara & Black Seas

- Questions over US$9 billion financing and viability

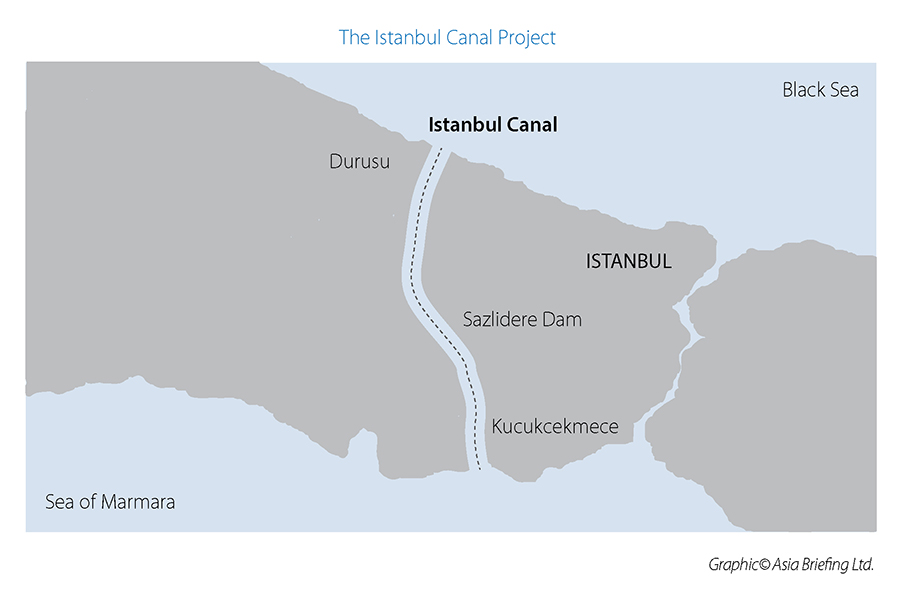

The Turkish government last month approved President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s plans to build a shipping canal in Istanbul similar to the Panama or Suez canals as an alternative to Turkey’s internationally used straits connecting Asia to Europe. The 45km (90-mile) Canal Istanbul is projected to cost US$9.2 billion and has been promoted as a smart investment that will pay returns in the form of shipping revenues and reduced traffic in the Bosphorus Strait.

It is not without its critics. Geopolitically, the project has cast concerns over Turkey’s commitment to the international treaty that governs shipping in the Bosphorus and Dardanelles straits.

It has also been labelled as another of Erdogan’s megaprojects that could endanger the environment, leave the state out of pocket, and leave the Turkish economy, which is heavily dependent on external financing, even more vulnerable to shifts in global investor sentiment

The Istanbul Canal is the latest in a string of infrastructure projects the government has embarked on since 2013, when Erdogan announced a US$200 billion, 10-year building spree.

The list of megaprojects completed so far includes one of the world’s largest airports, rail, and road tunnels under the Bosphorus and a suspension bridge linking Europe to Asia that ranks as one of the world’s biggest. A third pan-Bosphorus intercontinental bridge at the Dardanelles is due to be completed next year.

The government has promoted the canal for its potential to reduce the volume of ships using the Bosphorus – one of the world’s busiest and most difficult-to-navigate waterways. It is also highlighting the amount of money the canal could collect from ships passing through it.

However, critics note that Bosphorus traffic has fallen significantly in recent years, particularly as new pipelines make shipping oil and gas less efficient by comparison.

Between 2008 and 2018, the number of ships in the Bosphorus dropped from 54,400 to 41,100 a year, according to Turkey’s transport ministry. Shipping accidents in the strait have also fallen by a third since 2003, according to Turkey’s coastal safety agency.

Some are also questioning whether the canal will fill Turkey’s coffers to the extent anticipated by the government, noting that ships can currently pass through the Bosphorus for a nominal fee and there would be little incentive to pay to use the canal.

Moreover, previous megaprojects have left the public out of pocket when expected revenue failed to reach ambitious projections, leaving the state to fulfill guarantees for companies under build-operate-transfer contracts. The government reportedly paid more than US$515m in 2019 to the operator of the second Bosphorus bridge, opened five years ago, to cover a shortfall in anticipated toll revenues.

Critics have also said that the canal’s route would destroy lakes and rivers that supply Istanbul’s water and threaten marine and freshwater ecosystems. Gulcin Ozkan, professor of finance at King’s College London, said the cost-benefit analysis of such projects appeared “lopsided” from financial and environmental perspectives.

“Most megaprojects in Turkey entail significant environmental costs, as consistently put forward by experts, environmentalists and professional bodies such as the Union of Chambers of Turkish Engineers and Architects, and consistently disregarded by the government,”

Such counternarratives to the government’s canal pitch have fueled speculation that the greatest beneficiaries of the megaproject would be private contractors building a “new city” on 8,300 hectares (20,510 acres) surrounding the proposed canal.

Real estate companies’ shares rose as much as 8.65 percent on the Istanbul exchange after zoning plans for the canal were approved on March 27.

Istanbul Mayor Ekrem Imamoglu, who represents the main opposition party, has been a chief critic of the canal, describing it as “one of the biggest risks that this city had in its entire history”.

He has called for the money to be spent instead on public transport, water supply, social projects, education, and earthquake protection measures.

“The Canal Istanbul project is like major and risky surgery that no one would want to go through unless it’s totally necessary,” he told a meeting last year. “We’re talking about a surgery that will chop off the city and fundamentally damage its vital systems.”

The canal’s biggest foreign critic is Russia, which fears that Erdogan is building a new way for NATO warships to enter the Black Sea, where the Kremlin annexed Ukraine’s Crimea peninsula in 2014.

Approving the Canal Istanbul is only part of the battle to see the project through. Turkey is apparently willing to provide lease agreements to potential operators if they are prepared to help fund it – a direct appeal for Chinese BRI funding. With the potential benefits being in land acquisition and real estate development than the operations of the canal itself, China may decide it’s not prepared to invest in a Canal when profits will instead line the pockets of Turkish real estate investors.

Related Viewing

- Turkeys Pivotal Role in China’s Belt and Road Initiative with Europe, Central Asia, and the Middle East

- The Greater Eurasian Partnership: Connecting Central & South-East Asia

- The Suez Canal Alternative: The International North-South Transportation Corridor

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com