The Belt & Road’s Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor

Connecting China With Nepal and India May Be A Step Too Far For Delhi Even As Land & Talent Go To Waste

Although India is not officially part of China’s Belt & Road Initiative, it is involved. The Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor is a Belt & Road project that connects China with Nepal and India, although somewhat reluctantly on India’s part. The Himalayan Economic Corridor was initially a bilateral proposal between Nepal and China, with Nepal signing off on a Belt & Road MoU with China in 2017, having held numerous bilateral discussions with China on creating a corridor across the Himalayan Mountains. All bilateral projects along the Himalayas today form a part of the Himalayan Economic Corridor and by implication, the Belt & Road Initiative.

Beijing meanwhile is well aware of the political sensitivities in Delhi in creating a corridor connecting Kathmandu and Beijing. Kathmandu has long been part of Delhi’s sphere of influence, while the Himalayan Mountains themselves have acted as a land barrier between democratic Delhi and communist China. Tibet has sat in the middle, answerable to Beijing, while the frictions between China and India as a result of this in the early 1950’s lead ultimately to a short border war, which China essentially won. Delhi’s response at the time, and to some extent now, has been to keep the Himalayan regions – even those parts of Indian territory – undeveloped, in a “keeping China at arms length” border strategy.

That is now starting to unravel. China has been very active in developing infrastructure through Tibet, right through to the border with India, where smart new multi-lane highways come up to an Indian border devoid of infrastructure. This is causing concern for Indians on their side of the border, watching Chinese funded infrastructure and wealth being generated on the Tibetan side. The same is partially true in Nepal, and creates both consternation and embarrassment in Delhi.

Aware of this, and not wanting to push Delhi too far, Beijing proposed a more inclusive Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor to Delhi in 2014, which would see it develop into a trilateral project involving both China, Nepal and India. This proposal was based on an idea presented by former Nepalese prime minister Pushpa Kamal Dahal in 2010 to foster “trilateral strategic relations” between the three countries across the Himalayas. Beijing perhaps assumed that it would be easier to engage with Delhi if they were to include India in initial discussions. As it stands, this trilateral arrangement remains at the proposal stage, as the Indian government has yet to issue any formal response.

Kathmandu meanwhile has been enthusiastic about receiving larger amounts of Chinese investment. Nepal is reliant on India for the movement of its goods, is keen to reduce that dependence and wishes to present itself instead as a transit hub for cross-Himalayan trade. That would link it with China’s Yunnan, Sichuan and Gansu Provinces as well as with Tibet and allow it to process trade between China and India.

Dahal encouraged such collaboration, stating that the “Himalayas can no more be considered as barriers and obstacles. Instead, they can serve as important bridges that connect the two emerging regions of the Asian continent. Most importantly, connectivity lies at the heart of trans-Himalayan cooperation.” In 2010, Kathmandu and Beijing began discussing an extension of the Chinese rail link to Lhasa in Tibet and on to Kathmandu in Nepal, a connectivity and trade issue that was also followed up with the agreement of a China-Nepal Double Tax Treaty designed to reduce dutiable tariffs on included products.

By seeking to establish the Trans-Himalayan Economic Corridor with Nepal together with the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, Beijing is aiming to create an alternative to Kathmandu’s traditional reliance on Indian ports for trade and the movement of goods.

Beijing quickly began to emerge as an alternative to India for land-locked Nepal. While China initially was sensitive to Indian concerns about strategic connectivity with Nepal, an ill-considered 2015 India-Nepal blockade organized with the support of Delhi backfired, creating a fuel crisis across Nepal that highlighted Kathmandu’s reliance on India to facilitate trade and shipping. Amid the resulting tensions between India and Nepal, China announced the start of a new China-Nepal rail-road trading route, with an freight train loaded with 86 cargo containers carrying goods and fuel supplies from China’s western Gansu province, bound for Kathmandu. That has resulted in nine trading posts being identified in the Trans-Himalayan Corridor between Nepal and Tibet on a route that goes onward to the rest of China, although it appears not all may be feasible.

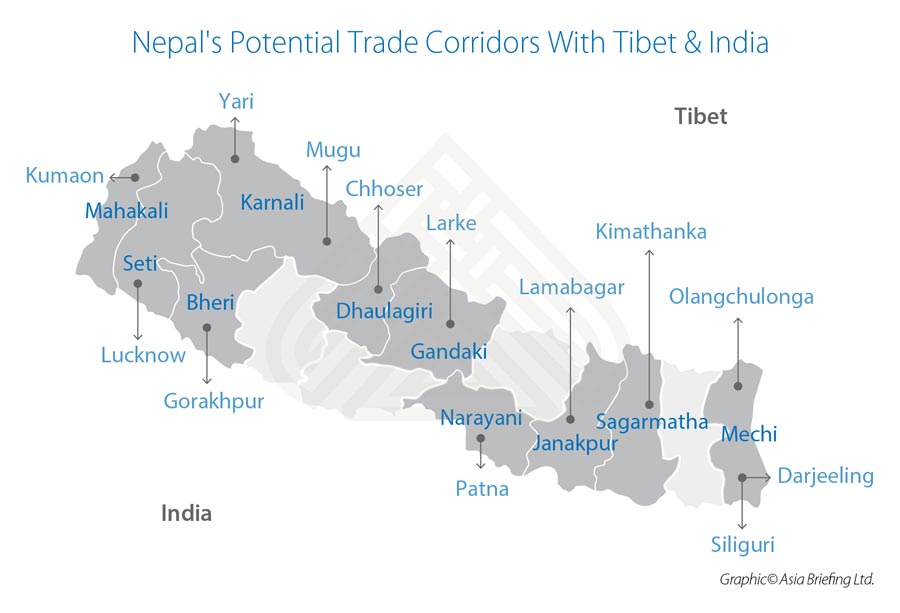

China has been keen to develop outlying towns of the Tibet Autonomous Region (TAR), and has done so with the Beijing-Lhasa railway being extended to Shigatse in 2014, Tibet’s second largest city. The Nepali government has also asked China to expand the Arniko Highway as a four lane highway connecting Tatopani, near Shitagse to Kathmandu. Along that route are seven proposed trading points – Yari, Mugu, Choser; Larke, Lamabagar, Kimathanka and Olangchula.

Another four possible economic corridors are possible in Nepal which link to both Tibet and to India. They are:

- Karnali Economic Corridor: Connects the Far West Region of Nepal with Tibet as well as Kumaon, in Uttarakhand as well as Lucknow.

- Gandhak Economic Corridor: Connects the West Region of Nepal with Tibet, and Gorakhpur in Uttar Pradesh.

- Bagmati Economic Corridor: Connects the Central Region of Nepal with Tibet and Patna in Bihar.

- Kosi Economic Corridor: Connects the Eastern Region of Nepal with Tibet, Sikkim, and Darjeeling.

India has watched these developments in its neighborhood closely. Since its independence, India has chosen to keep its Himalayan borders inaccessible and poorly connected, while China has aggressively sought to connect its borders, India neglected its own, creating massive disconnects between its borders and hinterlands, especially on its Himalayan front. By helping create multiple access points via roads and ports, China is able to present an alternative to South Asian nations and cultivate the means to challenge India’s role as a South Asian power.

Indian Rail From Leh To Arunachal Pradesh?

In response to China’s increasing presence along its borders, India began to formulate its own plans for regional connectivity in the Himalayas in 2013. The Indian Government proposed several “strategic rail projects,” including fourteen railway lines connecting its borders to foster growth in outlying regions. However, a lack of a strategic vision on India’s part led to slow implementation and delays. The current Modi government announced its intention in 2017 to fast-track railway projects on its Himalayan frontiers. The Himalayan Rail Express aims to connect India’s northern territory of Leh in Jammu and Kashmir to the eastern territory of Hawai in Arunachal Pradesh.

Seeking to cut across some of the world’s most difficult terrain and enhance connectivity with Bhutan and Nepal, this India-led rail link is as much strategic as commercial. Building up its border regions as opposed to keeping them disconnected will help India facilitate the movement of goods and troops from other parts of the country to this region. These initiatives constitute India’s response to past neglect of its border regions and China’s increasing commercial and military presence in contested areas. However, implementation challenges remain primarily due to the tough Himalayan terrain on the Indian side compared to better conditions on the Tibetan Plateau.

India Deliberately Keeps 1.41 Million Sq Km Fallow & 35 Million Citizens Underused Due To China Invasion Concerns

Delhi will have to continue to act and think rapidly when it comes to presenting alternatives to its landlocked neighbors, especially as China continues to woo them with alternative supply chains, infrastructure development suggestions and significant commercial benefits. Sino-Indian competition in the Himalayas is likely to intensify. Although India would benefit from tapping into Chinese investments to advance India’s own connectivity projects, a great deal needs to be done on the diplomatic front to allow any of these strategic connectivity plans to reach as far south as Uttarakhand, Uttar Pradesh, Sikkim and Darjeeling. The Indian military, and Army in particular meanwhile, needs to get over its fear that “China could just walk in if we build roads”. Troop warfare over the Himalayas is outdated. Conflict would be much more likely to be IT and energy driven, and in any case, roads and rail can be blown up. The Indian residents of the Provinces bordering Tibet and Nepal would also likely be rather more grateful for the increased trade opportunity, and the Indian Ministry of Finance grateful for taxable revenue increases through trade instead of keeping what amounts to about 1.41 million square km of land, and some 35 million citizens under-deployed for another few decades to “Keep China at arms length.” A rethink concerning the actual cost of maintaining the status quo, against the likelihood of security issues with China needs to take place.

As for Beijing, if it wishes to see the project come to fruition, it also needs to be prepared to settle with India and Pakistan issues concerning border disputes. Diplomacy and trade need to rather more than balance out the distrust.

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm provides business intelligence, legal advisory, tax advisory and on-going legal, financial and business operational support to investors throughout China, India, ASEAN and Russia, and has 28 offices throughout the region. We also provide advice for Belt & Road project facilitation. To contact us please email silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com