What is India’s “IDEAS” Belt & Road Alternative Project?

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Bringing the proposed Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Corridor and the BIMSTEC Nations into Focus

India’s recently announced “IDEAS” plan to act as a counter to China’s Belt & Road Initiative has its roots in an announcement in March 2018 by the Indian Finance Minister, Nirmala Sitharamen that the Indian Government would provide more resources and attention to the Indian Development Assistance Scheme (IDEAS). In the original manifestation of the concept, dating back to 2015, the Government of India supported Lines of Credit (LOCs) to countries in Asia, Africa, the CIS region and Latin America. The IDEAS concept essentially made the Indian Export-Import Bank the focal point for extending Indian Government lines of credit to countries deemed suitable for assistance. These countries are:

Sitharamen said that, as the sixth largest economy in the world, the Indian Government would provide more resources and attention to the Indian Development Assistance Scheme to allow India to provide concessional financing for development projects in the immediate and nearby neighborhood. “Considering our position as the sixth largest economy, we will analyze alternative development models that include private sector capital, multilateral financing, contributions from companies, non-residents, etc. I propose to renew IDEAS during the current financial year.” Sitharaman stated as part of the new Indian fiscal budget just a couple of weeks ago.

China & India’s Belt & Road Rivalry in Africa

At stake are two main issues. One is the power-broking in Africa, which has long been divided upon managerial and investment lines of the Chinese diaspora dealing with trade, the Indian diaspora inserting themselves into the civil service, and the Europeans providing the finance. That balance is now changing as Beijing sees the Chinese diaspora in Africa as a useful tool and wants to increase its regional involvement and now lobbies African Governments directly in a manner that India has not. Beijing has been successful; India’s total trade with Africa during 2017-2018 was US$62.69 billion, while China’s African trade exceeded US$220 billion, a reversal of the norm in just one decade.

Caught napping on the job, the Indian Government now wish to provide more competition for China, and especially in the Africa. The revamps of IDEAS goes hand in hand with recent Indian Government initiatives to add a further 18 Indian diplomatic missions in Africa. That was announced in March 2018; since then Delhi has opened Embassies in Rwanda, Djibouti, Equatorial Guinea, the Republic of Guinea and Burkina Faso, with another four to follow before the year end.

India’s Exim Bank has also taken on a strong African flavor of late, concentrating several of its loan/aid programs in Africa. But India has a long way to go before it can be a counterattack to the overwhelming presence of China on that continent. Chinese President X Jinping recently announced more than US$60 billion in aid to Africa, and have stumped up US$1 billion for a new China-Africa Belt & Road Fund – these are tough numbers for Delhi to match.

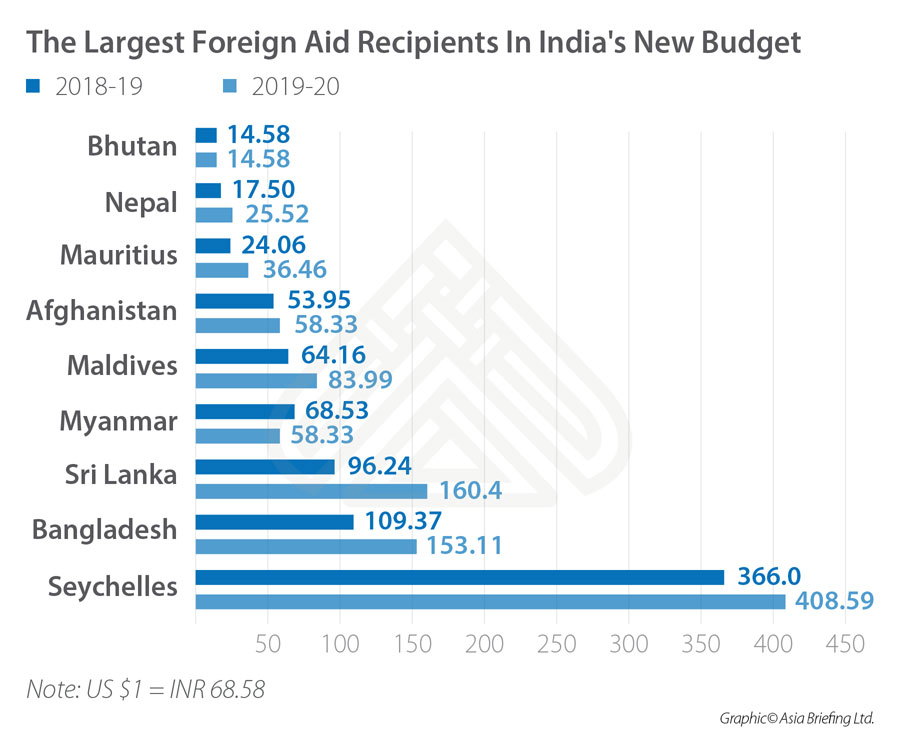

But India is also dipping into its own pocket, and has increased its foreign aid budget by some US$2.1 billion. While a large chunk of that goes to countries directly within India’s sphere, such as Bhutan, Nepal, Mauritius, Afghanistan, Myanmar, Sri Lanka and Bangladesh, African nations are also getting a significant increase in Indian aid.

In fact, the Indian-Africa corridor is one of the routes China had identified as part of the Belt & Road Initiative. One can imagine the consternation in Delhi when news appeared in Chinese newspapers that Kolkata would be part of China’s Maritime Silk Road. Although the Chinese might have been a bit cheeky in announcing that, India has played ball to some extent – it wants Kolkata to develop as a Port serving North India, as does Bangladesh as a compliment to Dhaka. China wants Kolkata to help provide trade access to Tibet. That all makes sense, however India is wary of having the Chinese so close, and the main Port at Dhaka is primarily Chinese funded, as is the main Port at Sri Lanka’s Colombo, currently under construction.

That said, both China and India are looking to take advantage of Africa’s new African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AFCFTA) which came into effect a month ago and reduces cross-border taxes om much of pan-African trade. This has a significant impact on Chinese and Indian businesses already invested there – as many have been for generations. I discussed the impact of AfCFTA and China in the article China’s African Moves Through The Belt & Road, Double Tax Treaties And AfCFTA. It is an existing Indian diaspora that Delhi also wants to assist to further promote and develop India-African trade. That was noted by Sitharaman in her budget and the increased funding for the IDEAS programme when she stated “It will also allow us to provide better and more accessible public services, especially for the local Indian community in these countries.”

China’s Increasing Presence in India’s South-East Asian Backyard

Although a triumvirate of Dhaka, Kolkata and Colombo Ports would be a boost to Asian-African trade, there are other potential geopolitical considerations too. One of the most explosive is the proposed Kra Canal project, which would cut a huge amount of shipping time between India and China – goods currently have to pass through the Malacca Straits. The issue for India is who would operate it, as it effectively also acts as a conduit between the South China Sea and the Indian Ocean. It would also signal the demise of Singapore as a vital Asian Port, and consequently is a highly contentious ambition. Not surprisingly, the Governments of China and Thailand are for the project – provided it would be financed by China. The cost? An estimated US$30 billion, meaning it is unlikely to be on the operational agenda anytime soon. Nonetheless, India has concerns about the extent of China’s Belt & Road – although it has nothing against the development of Kolkata as a hub.

In fact, India’s position as a Belt & Road Initiative player is somewhat ambiguous, as I pointed out in the article China’s Belt & Road Initiative: India. India’s concerns are essentially of a geo-political and territorial nature, however that doesn’t stop Delhi getting involved when it suits. India is a major investor in the Asian Infrastructure Development Bank and a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation, while much of the recent reboot of the IDEAS aid programme went to countries that are also heavily invested in China’s Belt & Road Initiative. We can examine the top most funded countries under that, as according to the recent Indian budget as follows:

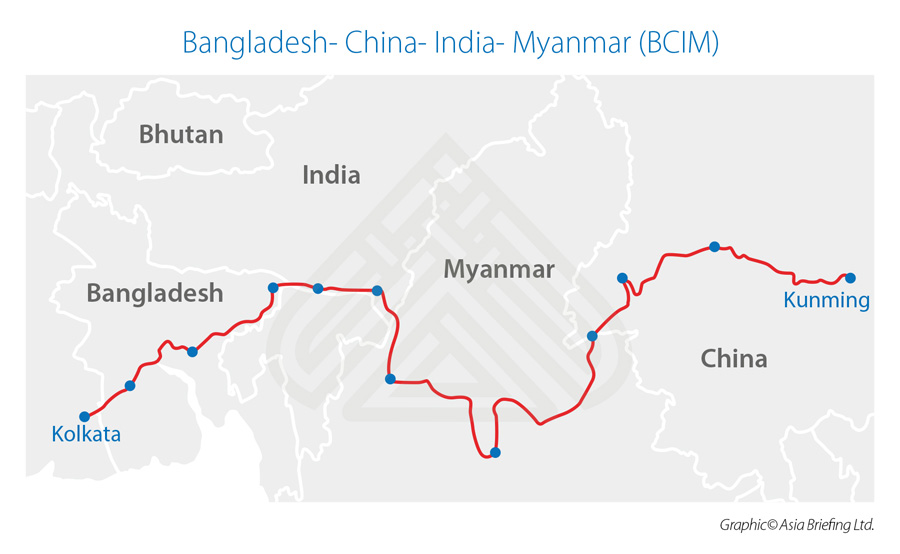

India also participates in what are essentially regional Belt & Road projects, on the flimsy basis that the groundwork for these had been implemented before China announced the initiative, and therefore they are not really BRI deals. An example is the proposed Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIM).

The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor

The BCIM Economic Corridor is a Chinese proposal that predates Xi’s BRI, and seeks to build on the historic links between the eastern Indian subcontinent and southwestern China through Bangladesh and Myanmar along what was known as the Southern Silk Road, and during World War II the Stilwell Road. It aims to connect the Chinese city of Kunming with the Indian city of Kolkata through Dhaka in Bangladesh and Mandalay in Myanmar, seeking to boost trade, build infrastructure, and connectivity between these countries. Originally called the Kunming Initiative, it has been under discussion since the 1990s and looks to develop tourism, transportation, and trade routes. The BCIM Corridor has encouraged positive engagement between Delhi and Beijing, as one of the few bright spots in an otherwise rocky Sino-Indian relationship. In 2015, Indian Prime Minister Modi and Chinese President Xi “Welcomed the progress made in promoting cooperation under the framework of the BCIM, and agree to continue respective efforts to implement understandings.” India and China have consistently expressed diplomatic support for the BCIM Corridor, keeping in mind the need for dialogue in the Sino-Indian relationship. However, despite this positive rhetoric, much of this enthusiasm is largely symbolic; effective cooperation through the BCIM Corridor has been seriously limited and little concrete work has been carried out. There is a widespread sense that India is playing for time as it debates the costs and benefits of working with China in the region.

However, like China in other regions, India has also been busy institutionalizing parts of Asia, and especially those within its immediate orbit. This includes the BIMSTEC grouping.

The Bay of Bengal Initiative for Multi-Sectoral Technical and Economic Cooperation (BIMSTEC)

BIMSTEC is not a Belt & Road Initiative project as it does not include China, but it is integral to the BRI as it includes India and its neighbors Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, Nepal, Sri Lanka, and Thailand. Connectivity cooperation is one of the core pillars of cooperation among the BIMSTEC members, both with each other and among individual members with neighboring BRI infrastructure. BIMSTEC is a formal body, headquartered in Dhaka, with 1.5 billion people and a combined GDP of US$3.5 trillion (2018). The BIMSTEC member states are the countries dependent on the Bay of Bengal. Fourteen priority sectors of cooperation have been identified and several BIMSTEC centres have been established to focus on those sectors. A BIMSTEC free trade agreement is under negotiation, while the Asian Development Bank is a Partner organization. The BIMSTEC Free Trade Area Framework Agreement (BFTAFA) has been signed by all member nations to stimulate trade and investment in the parties, and attract outsiders to trade with and invest in BIMSTEC at a higher level. Subsequently, the “Trade Negotiating Committee” (TNC) was set up, with Thailand as the permanent chair, to negotiate in areas of trade in goods and services, investment, economic co-operation, trade facilitations and technical assistance for LDCs. Once negotiation on trade in goods is completed, the TNC would then proceed with negotiation on trade in services and investment. A proposed BIMSTEC Coastal Shipping Agreement was discussed in December 2017 in Delhi, to facilitate coastal shipping within 20 nautical miles of the coastline in the region to boost trade between the member countries. Compared to the deep sea shipping, coastal ship require smaller vessels with lesser draft and involve lower costs. Once the agreement becomes operational, cargo movement between the member countries can be processed through more cost effective, environmentally friendly and faster coastal shipping routes.

India’s IDEAS Initiative – Complimentary To China’s Belt & Road Initiative.

India’s IDEAS programme therefore is not anything especially new, but it is an Indian concept of providing funding and development, mainly related to trade, across South-East Asia and Africa. In fact it predates the Chinese Belt & Road Initiative. What has happened is that the BRI has developed so quickly, and so widely, that India has had to take greater notice and start to refinance and reorganize its own initiatives in order to maintain their relevance. The regeneration and refinancing of the IDEAS programme is just that.

On the downside, the heart of the matter however remains the traditional China-India distrust, which effectively stems back to the early 1950’s and the absorption of Tibet into China. That led to border disputes, and a collision between a newly democratic India and a newly communist China. Understandably, that rubbed everyone up the wrong way and has resulted in long-standing border disputes and a brief war. China’s support for Pakistan, partially designed to keep India occupied on its Western front, has also had the desired effect. Some of India’s response has also been self-damaging in the longer term – a policy of keeping the Himalayan regions under developed has now seen China move into areas of Tibet and Nepal that possess far more advanced infrastructure than exists on the Indian side. Dealing with that is an Indian conundrum for it to solve. The positive aspect of India’s IDEAS initiative is that now Delhi is starting to take that challenge seriously and do something about it. The intriguing aspect of India and the Belt & Road Initiative is that while in public, India remains aloof, over future years the IDEAS initiative and the BIMSTEC grouping are going to be anything but.

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm advises Governments and MNC’s on matters of Belt & Road Initiative intelligence as well as foreign investment matters throughout the Asian region. We have offices in India, in addition to China and the ASEAN nations. For assistance with Belt & Road Initiative matters with India please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com