Uzbekistan Re-Energizing as Central Asia’s Traditional Hub for the Silk Belt and Road

Tashkent, Uzbekistan’s Capital City

Back in 2013, while based in the Dezan Shira & Associates Singapore office, I applied for a visa to visit Uzbekistan. The country had an Embassy in the city and I was intrigued to find out what was going on in the country, prompted in part, by Chinese President Xi Jinping’s state visit there in September that year. At the time, Uzbekistan was ruled by President Islam Karimov, who by then had ruled the country for 24 years. It had been a fractious rule, Uzbekistan constantly quarreled with its neighbors, with Karimov essentially ruling with an iron fist. Although he retained warm relations with Beijing, he was a throwback to the old Soviet era – trust no-one, and while you’re doing that, mess them about as much as you can for good measure.

I applied for a single entry visa, and was told to purchase, in advance, a return flight ticket to Tashkent, which I did, routing from Singapore via Delhi. It was on Uzbek Airlines and as they were the only carrier, the flight was expensive. Then my visa application – for which I had also paid a significant amount of money for in advance, began to run into problems. The hotel I had booked “had verification problems”, they asked me for a complete breakdown of my travel plans, including bus timetables for a planned trip to Samarkand, then questioned both the validity of my Singapore residency and finally wanted a new photograph. I was finally told to pick up my passport, with the issued visa, at 16:00 on the Thursday. Yet they knew full well the flight to Delhi and onto Tashkent departed Singapore at 16:30.

That was not my first experience of Soviet style buggeration – China had had its moments too – but it stymied my planned trip to Uzbekistan. I never got refunds for the flights either – officially I was a “no show” and that meant missing the plane was my responsibility.

I tell this story as it highlights the changes that have come over the country since then. No one knew at the time, but Xi’s visit back in 2013 was part of his research into sounding out the Central Asian nations as to the viability of what would just two years later become his Belt and Road scheme. Karimov, whose policy towards foreigners was never warm, died in 2016. Since then, much to considerable relief, his eventual successor – Karimov had not expected to die, ever – was Shavkat Mirziyoyev. Little known at the time, he has overturned a lot of Karimov’s previous policies and has begun to embrace both his neighbors and foreign investment.

Mirziyoyev has, over the past three years, initiated a series of important reforms, and made unprecedented overtures to each of Uzbekistan’s previously estranged neighboring states. His initiatives have included currency reform, trade liberalization, improvement of the business climate, reform of the cotton industry, simplified entry for foreign nationals, and welcoming investment and development banks and financial institutions back into Uzbekistan. Along with North Korea, Uzbekistan has been one of the few countries in the world to maintain an exit visa regime for its own citizens, but next year this too will be scrapped.

Mirziyoyev’s recognition for state change and reform in Uzbekistan hit the ground running. In the first twelve months of office, he visited Kazakhstan four times, Turkmenistan three times, and Russia twice, in addition to China, Kyrgyzstan, Saudi Arabia, Turkey, and the United States. He also brokered a peace deal with neighboring Tajikistan, which despite being an important next door neighbor with a border to China had been cut off by Karimov’s policy of laying minefields between the two countries and sealing the border. Today, Uzbeks and Tajiks share a 30 day visa-free arrangement, direct passenger flights between the two countries have recommenced after 25 years, and freight trains cross over the borders. Ten of the 16 border checkpoints with Tajikistan that were previously closed have been reopened, with the remainder under discussion pending ordinance clearing and related security matters.

If one country can be shown to have been re-energized due to China’s Belt and Road Initiative, then it is Uzbekistan. China is heavily involved in rail construction in the country, and has assisted with electrifying the Bukhara-Misken rail line.

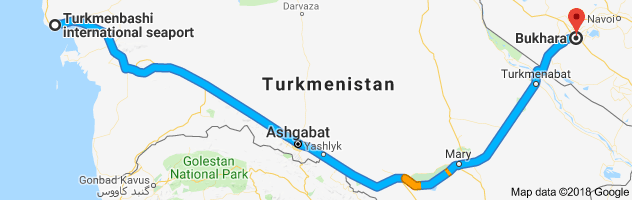

That has considerable trade significance for Uzbekistan as the Bukhara link also connects south to Turkmenbat in Turkmenistan, which then runs west to Turkmenbashi Port on the Caspian Sea. Uzbekistan is landlocked; the Bukhara rail line – which also runs north to Tashkent, the capital city, provides the country with new export potential for its products.

Elsewhere, Uzbekistan has also been modernizing. It possesses a high-speed rail service running between Tashkent and Samarkand, with a recent extension to Bukhara. This reduces the length of the Tashkent-Samarkand trip to just two hours, and the full journey to Bukhara 3.5. This indicates the potential for trade traffic between Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan is set to grow significantly now the latter’s Caspian Sea Port at Turkmenbashi has opened. Driving that is a 16.5 hour stretch along the M37 Highway. When the train route is fully operational, transshipment will be far easier and faster.

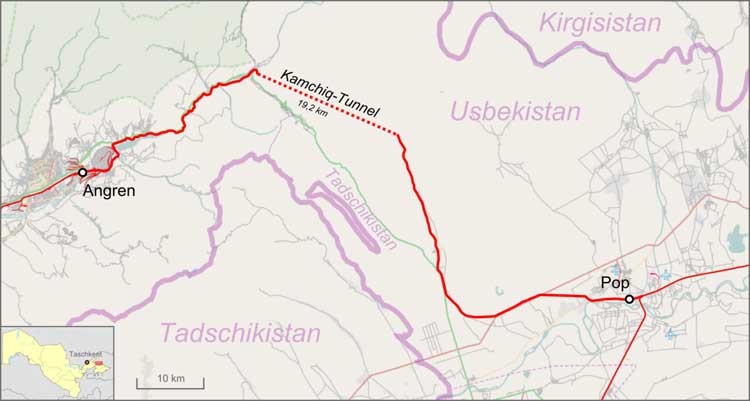

China has also been busy in assisting Uzbekistan to improve its connectivity with Tajikistan. It has a vested interest in this for a number of reasons; the policy of peace via trade, keeping Islamic militancy at bay and less able to give momentum to troubles in Xinjiang Province, and better linking the Central Asian states for market access. That gains Beijing both imports and exports, but more of an economic lever over the region. To that end, Chinese engineers constructed – in just 900 days – the 9.2 km Kamchiq tunnel, a key and difficult section of the 169 km Angren-Pap railway, which passes through the Qurama Mountains, Central Asia’s longest mountain range. The railway is now fully operational.

China, meanwhile, shares a 414 km border with Tajikistan in Xinjiang province, and eventually hopes to connect the main border crossing there at the Kulma Pass with its own rail network. The Kulma Pass, however, is in high Pamir Mountain territory, and although now boasts a paved vehicular highway, is only usable between May and November. China, along with Afghanistan, Iran, Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan are also discussing a planned rail network to link all these nations, although engineering solutions and the cost factor still represent significant challenges. At present, the usable viability extends from Iran, up through Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan and halts in Tajikistan.

To the north, and the long, 2,330 km border with Kazakhstan, relations and connectivity are also starting to improve. Kazakhstan has a direct overland route from China to the Caspian, and has been making full use of its Belt and Road geographical advantage. Under Karimov, however, bilateral relations between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan were fractious and little legitimate bilateral trade occurred, although smuggling, including a vibrant drugs industry was rife. Under Mirziyoyev, however, there has been a complete reversal of that policy.

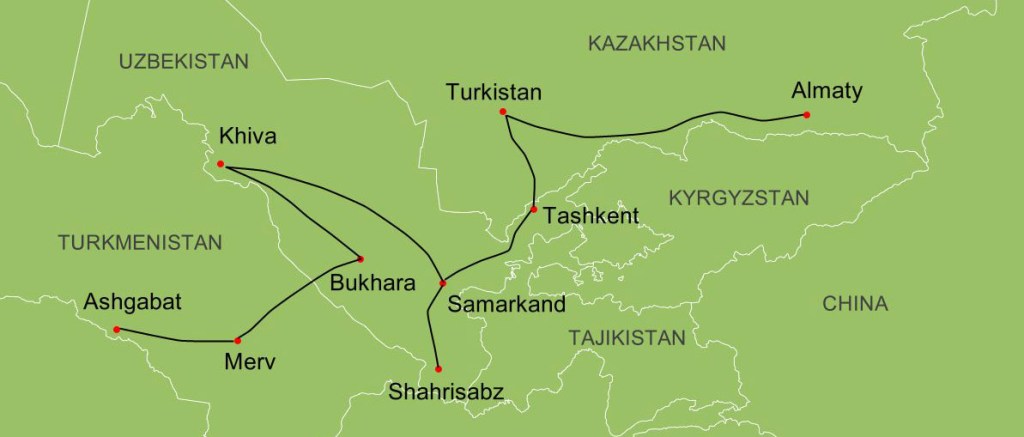

In March last year, meetings between the two Presidents realized an announcement that the two countries had reached an agreement to create a high-speed passenger train link between Almaty and Tashkent. Kazak President Nazarbayev noted that trade and connectivity interaction between the two nations had intensified, stating that “In the first quarter of this year (2017), there has been an increase in business relations in a variety of economic sectors. It is worth highlighting the transportation-logistics sphere and auto-manufacturing, and also to mention regional cooperation in a broad spectrum of issues. Trade turnover in the first three months of 2017 increased by 37 percent.”

The high-speed train, known as the “Tulpar-Talgo” was quickly put into operation. B. Egamberdiev, Uzbekistan’s head of Department of the Uzjeldorpass (train service) said, “The Tulpar-Talgo train on this route has more than 400 seats. It will link the major tourist centers of Almaty and Tashkent. Our citizens are interested in visiting the Alpine resorts of the large local metropolis. From Kazakhstan to us, tourists traveling to see our historic town of Samarkand, Bukhara, and Khiva.”

Currently, the train operates twice a week, departing from Almaty on Mondays and Saturdays, and from Tashkent on Tuesdays and Sundays. The travel time about 16 hours and 30 minutes. In the future, the frequency is expected to increase.

I already discussed how Turkmenistan was using its new Caspian Sea Port at Turkmenbashi to connect via rail to its capital Ashgabat and then head north to the Uzbekistan border at Bukhara. With high-speed rail now connecting Bukhara with Tashkent, and Tashkent now employing a twice weekly high speed service to Almaty, Central Asia is starting to resemble the old children’s song “The knee bone is connected to the thigh bone”, and so on.

The implications for Uzbekistan are huge. Regional connectivity is breaking out all over. For what for much of the last 25 years had been an isolated, fearful, and closed nation, a blossoming is beginning to appear, with Uzbekistan reclaiming its position as a major Silk Road Hub.

As for my travelling to Uzbekistan? I eventually made it, two years later. I don’t write about countries I don’t know and haven’t been. And as both Moscow and Beijing appreciate very well when it comes to Central Asia, if at first you don’t succeed, try, try and try again. And read Silk Road Briefing to appreciate how both Uzbekistan’s northern and southern regions are the most viable for investing in Uzbekistan’s position on the Belt and Road routes.

Uzbekistan Fast Facts

Uzbekistan Fast Facts

Size: 448,978 sq km (slightly larger than Sweden)

Population: 33 million

GDP (PPP) US$242 billion (2017)

GDP Per Capita (PPP) US$7,524

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm provides risk assessment, business intelligence and professional services throughout Eurasia, and maintains a Belt & Road desk. Please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

Related Reading:

Related Reading:

![]() Aqtau Port, Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea Belt & Road Window To Europe

Aqtau Port, Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea Belt & Road Window To Europe

![]() Uzbekistan Completes High Speed Bukhara-Misken Rail Link

Uzbekistan Completes High Speed Bukhara-Misken Rail Link

![]() Uzbekistan, Tajikistan Set to Restore Normal Relations, Offering China Easier Access to Central Asia via Xinjiang

Uzbekistan, Tajikistan Set to Restore Normal Relations, Offering China Easier Access to Central Asia via Xinjiang

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.