Turkmenbashi’s Caspian Window and the Turkmenistan Belt and Road

Turkmenbashi SeaPort

It remains unknown whether any Chinese official, upon hearing of the One Belt, One Road idea asked the Chinese President Xi Jinping what to call the Caspian Sea part. The Belt refers to the maritime section of the project, encompassing much of South-East Asia, then eventually washing up at Piraeus Port in Athens, while the Road follows the overland route. This means the Caspian section is to some extent an anomaly, in that it is part of the “road” yet needs to be navigated by ship. Which is a bit of an issue when you are a Chinese freight train.

Accordingly, just like the ancient Silk Road routes that had to tackle and avoid the Taklimakan Desert (the name means “Go in and you won’t come out” in Uyghur) the Belt and Road also tries to avoid the Caspian as one route passes to the north of the Caspian by heading from China and up into Russia, then heading west using the trans-Siberian rail route, or south by taking advantage either of rail links into South-East Asia (a route currently stymied by Malaysia, who do not want a high rail speed link with Singapore as it will compete with the lucrative Kuala Lumpur-Singapore flight schedule) or via ship from Hong Kong, Shenzhen, or other southern Chinese routes. Which would be fine, except that large parts of China’s massive interior provinces, such as Sichuan, Gansu, Ningxia, and Xinjiang would be cut off from direct connections heading west. Consequently, both Kazakhstan, and to a more recent extent, Turkmenistan and crossing the Caspian Sea have became strategically very important for China’s Belt and Road ambitions.

The Caspian Sea itself is a mighty body of water, and there are no passenger only cruise ships on these waters. It is the largest enclosed inland body of water on our planet by area, and borders Kazakhstan to the north-east, Russia to the north-west, Azerbaijan to the west, Iran to the south, and Turkmenistan to the south-east.

Geographically, it also has interesting characteristics – the sea bed in the southern part reaches 1,023 meters (3,356 feet) below sea level, and is the second lowest depression on earth after Lake Baikal, also on the Belt and Road in Siberian Russia. The Caspian is, therefore, classified as either the world’s largest lake – waters naturally flowing into it from its massive catchment area as no rivers feed the Caspian – or as a fully fledged sea, depending on whose definition one cares to use. It is technically known as an endorheic basin and is further distinguished by its waters – which have a salinity of about a third of most seawater. The surface area is 371,000 sq km (143,200 sq miles) – a bit larger than Germany or Japan, and about 1.5 times the size of the UK.

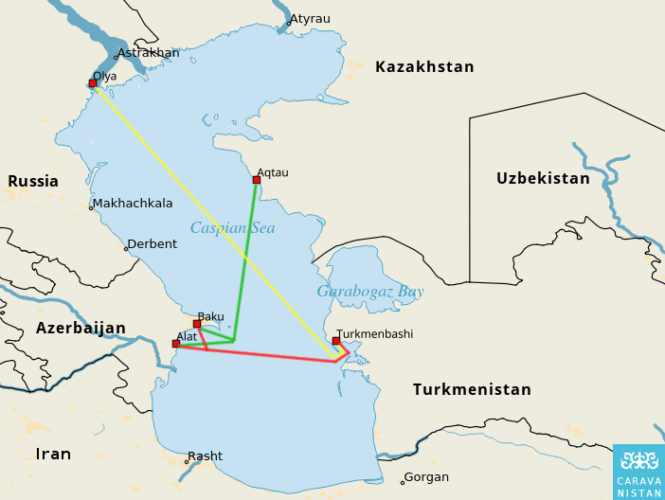

There are several routes across the Caspian, all operated by cargo ships, although these do take passengers. The main western port of exit is Baku, in Azerbaijan, then heading either north-east to the Kazak Port of Aqtau,or directly across to the new main Port of Turkmenbashi, in Turkmenistan. There is also a route from Olya in Russia heading to Turkmenbashi.

The Turkmenbashi Port opened for business just last month, at a cost of US$1.5 billion, with Turkmenistan looking to the facility to improve the country’s export prospects and establish it as a regional hub connecting Europe and Asia. Turkmenistan wants to diversify its economy, which largely depends on natural gas exports for revenues and is a main source of hard currency. That took a hit in 2016 when Russia, once its main customer, stopped all purchases following a pricing dispute.

While the country is reluctant to open up its borders, it is hoped that Turkmenbashi Port will triple Turkmenistan’s cargo handling capacity to 25-26 million tons a year. At the Port’s opening ceremony, Turkmen President Gurbanguly Berdymukhammedov said the new port will be an important link in a modern maritime transport system giving users favorable conditions for access to the Black Sea area, Europe, the Middle East, and Asia, and that Ashgabat is ready to discuss use of the seaport with its landlocked neighbors – a reference to Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. Of interest is that the Turkmenbashi Port and the Ferry to Baku can accommodate freight trains, which are loaded straight from the railway lines onto the ship, which has a special rail container section also containing rail tracks. These are then rolled off onto rail tracks in Baku.

Turkmenistan already has a railway link with China through neighboring Kazakhstan and the new port could help Ashgabat win some of the cargo flows moving between China, the Middle East, and Europe. That rail link is also likely to be accompanied by a new highway connecting Turkmenbashi via Garabogazthrough to Kazakhstan – a 242 km journey. At present, however, the road looks like the image below, which is indicative both of infrastructure that still needs to be built, but also the strides the nation made with developing the Turkmenbashi Port.

It remains to be seen how much impact the new port, rail, and road links will have on Turkmenistan. These are huge steps for it to be taking after years of an isolationist policy. Chinese influence, though, appears to be persuading Ashgabat to open up and become more connected, while Ashgabat traders are already familiar with Western China, often visiting markets in Urumqi to bring back cheap products for resale.

Turkmenistan, however, courtesy of its ex-Soviet past, does possess a reasonable, if old rail network. With the hard work of getting the track built through difficult terrain long completed, upgrading it is an issue the Chinese are very much interested in – yet Ashgabat will need careful wooing to allow it to get beyond the thinking that train tracks can be used as precursors to invasion – a somewhat irrational fear but one shared by the Mongolians – and being subservient to Beijing in terms of development loans. This status of remaining “on the fence” is mirrored by Turkmenistan’s role within the Shanghai Co-Operation Organisation – it is an Observer nation only, and does not engage.

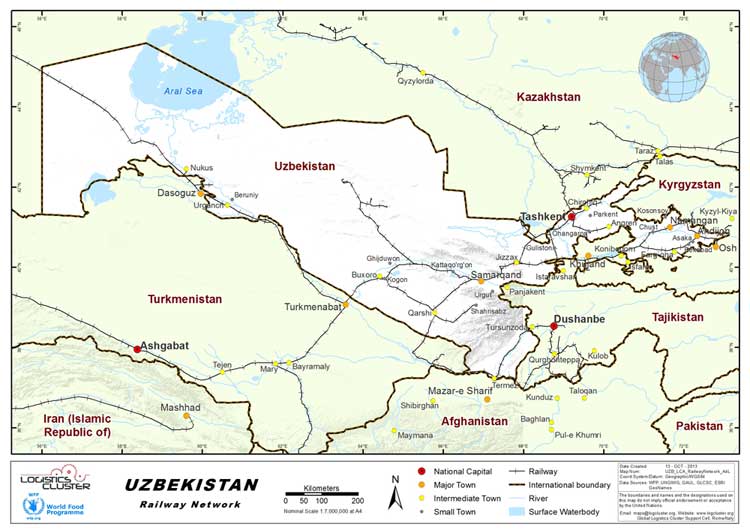

Nevertheless, it possesses useful rail links with Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and Afghanistan, and with its new port is in a position to wield some influence over its landlocked neighbors. Afghanistan, long mired in conflict, is a concern to Beijing as it does not want militant Islam impacting on Xinjiang Province. Reluctant to get involved in military operations, the Chinese instead have been patiently building up relationships and regional stability via trade. The general viewpoint being that if people are becoming wealthy, they are more likely to put aside local grievances and lay down their weapons. It is a strategy that appears to be working. Turkmenistan’s archaic rail link to Afghanistan is currently being upgraded, with longer terms plans to extend that through to another landlocked nation – Tajikistan.

Turkmenistan is also looking to upgrade its rail connectivity through to Uzbekistan, with the existing line heading north from Ashgabat, up through Turkmenbat and onto Bukhara, itself an ancient Silk Road City. As Uzbekistan has recently normalized relations with Tajikistan, inter-regional rail connectivity as well as through to China’s Xinjiang Province is also likely to be improved.

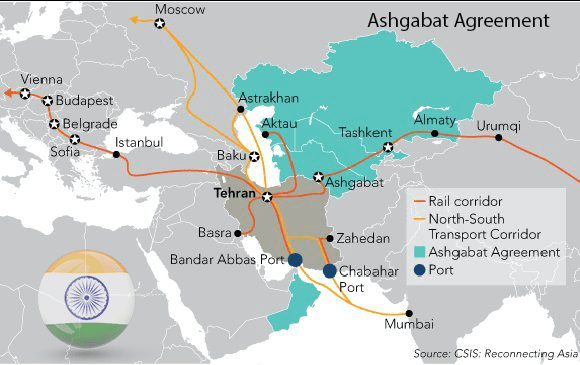

These routes, along with the Lapis Lazuli Corridor, are part of the Ashgabat agreement, which is is a highly ambitious, multi-modal transport agreement between Turkmenistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, Oman, and Pakistan for creating an international transport and trade corridor facilitating transportation of goods between Central Asia and the Persian Gulf. In October 2016, Pakistan had formally joined the Ashgabat Agreement in addition to the Lapis Lazuli corridor. Interestingly, the Indian government has also requested approval for acceding to the agreement. India’s intention to accede to the Ashgabat Agreement, which was made in 2016, is now being conveyed to the Depository State – Turkmenistan. India would then become a party to the Agreement upon consent of the founding members, opening up the Ashgabat Agreement to India’s own massive rail network connectivity. When completed, the entire network will look like this.

At present though the key lies in the success of the Turkmenbashi Port, as this provides, for Turkmenistan at least, a window onto the Caspian. It faces competition from Kazkahstan’s Aqtau Port further to the north, however, when one considers the immense Central Asian connectivity these ports will ultimately be delivering, the potential is huge. Consequently, Turkmenistan’s position as a Belt and Road corridor and access to Baku and onto Europe, has, with the development of the port, the potential to radically change the face and destiny of the entire country.

Turkmenistan Fast Facts

Turkmenistan Fast Facts

Size: 491,210 sqkm (roughly the size of Spain)

Population: 5.6 million

National GDP (PPP): US$103 billion (2017)

GDP per capita (PPP): US$18,771

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm provides risk assessment, business intelligence and professional services throughout Eurasia, and maintains a Belt & Road desk. Please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

Related Reading:

Related Reading:

![]() Central Asian States Create New C5+1 Consulting Group

Central Asian States Create New C5+1 Consulting Group

![]() Turkmenistan’s OBOR Contributions – Gas, Tourism & Light Trade Potential

Turkmenistan’s OBOR Contributions – Gas, Tourism & Light Trade Potential

![]() China’s Silk Road Gold Fund – The Central Asian Gold Deposits (Part 1 of a 5 part series)

China’s Silk Road Gold Fund – The Central Asian Gold Deposits (Part 1 of a 5 part series)

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.