Iran’s Approach to the North and South Transport Corridors: Obstacles & Future Prospects

By Farzad Ramezani Bonesh

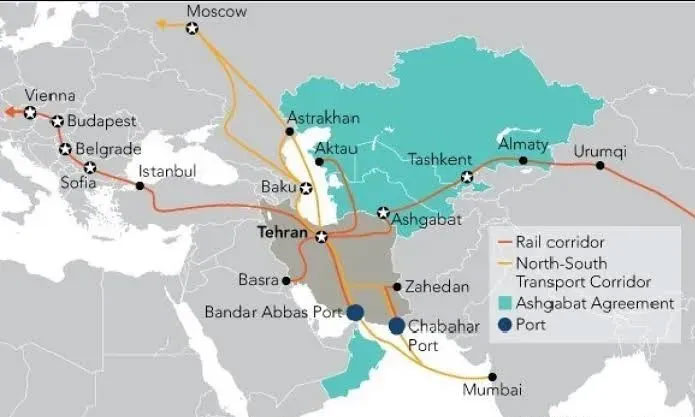

The International North–South Transport Corridor (INSTC) was established by Iran, Russia and India in September 2000, and subsequently expanded with the admission of 13 major corridor members such as Azerbaijan, Belarus, Armenia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Oman, Russia, Tajikistan, Turkey, Ukraine, and the observer membership of Bulgaria.

The INSTC connects India to the Caspian Sea, Russia, and Northern Europe through Iran. By bypassing the Suez Canal, the route is 40% shorter and 30% cheaper than traditional routes in terms of distance and time.

This corridor combines trade in three western, Eastern, and Central routes with road, rail, and sea routes. The INSTC’s western route passes through Russia, South Caucasus, and Iran. The middle axis reaches India through Saint Petersburg – Astrakhan – Caspian Sea – North and South ports of Iran (Amirabad, Anzali, Chabahar, and Astara ports).

The eastern axis passes through Russia-Kazakhstan-Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan-Iran. In the last two decades, the main partners of INSTC have tried to operate the corridor. But the events such as the Suez Canal incident in 2021 and the Ukraine crisis, lead to more emphasis on north-south axis. In June 2022, the trade on the INSTC route started with a shipment from Russia to India via Iran.

Iran’s approach and opportunities along the INSTC

Long beaches, special transit, and geographic location, and easy access to the sea and other countries are poised to make Iran one of the highways of trade, with several international corridors already passing through the country. With the INSTC, Tehran is attempting to be a connecting pole between ECO, ASEAN, EAEU, GCC, India, Central Asia, the Middle East, the subcontinent, and North and East Europe. All branches of INSTC pass through Iran and it is the key crossing of INSTC for Russia and India.

Pursuing the INSTC is of special importance for Tehran, and it has made efforts to rebuild its position to become one of the most economical transit routes. By the activation of all the links of the multi-modal network chain (7200 km), Iran can work with member countries in expanding the transport relations and increasing the access of the parties to the world markets.

From Tehran’s point of view, the INSTC, coupled with the Ashgabat Agreement of 2018 5(with the participation of India, Oman, Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan) can facilitate the transportation of goods between Central Asia and the Middle East.

In the “Look East” roadmap, Tehran is increasingly focused on strengthening relations with Russia and India. In the past year, the numerous meetings of the officials of Iran and India, the necessity of preparing a road map for advancing comprehensive and extensive strategic relations, examining important issues such as de-dollarization, the removal of sanctions, and increasing participation in trade and transportation, are all under consideration.

Since the beginning of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, the strategic importance of the INSTC has become especially important for Moscow and Tehran. Both are facing Western sanctions. Therefore, the better activity of INSTC is important to facilitate and accelerate the process of de-dollarization and neutralize Western sanctions.

Currently, cargo related to Russia is unloaded at the Sarakhs terminal in the northeast of Iran, and a large volume of trade between India and Russia is carried out through Iran.

From Tehran’s point of view, completing the corridor chain is one of the main priorities of the government, with the INSTC to be completed by the current government.

Iran’s President, Ebrahim Raisi, has also spoken about the serious pursuit of the government’s plans such as the Chabahar-Zahedan railway and the connection of the Oman Sea and the Persian Gulf to Europe in order to strengthen the transit position.

The development of Chabahar port, the formation of the Makran Coastal Development Organization, and the “Special Plan for the Development of Makran” are parts of Iran’s plan to become a regional transit hub.

From this perspective, Iran’s ports in the north and south have the capacity to move 270 million tons of goods annually, and by increasing the capacity of the country’s southern and northern ports, developing rail, sea, and road transportation lines, and INSTC, Iran’s economic diplomacy can be strengthened.

The signing of the Russia-Iran joint cooperation agreement for the construction of the Rasht-Astara railway with Tehran solves the missing link of the western route of the INSTC. When completed early in 2024, 10 million tons of cargo will be able to be moved, rising shortly to 15 million tons with goods moving equipment.

In addition, with the existence of more than 14,000 km of railways in Iran, the development of lines and the INSTC leap plan, and the approval of 6 measures and infrastructure projects by Tehran, Iran’s Transport Development Fund is also looking for the participation of the private and foreign sectors, especially India and Russia, to provide financial resources, and the implementation of many transportation projects, especially to the east of Iran. Russia’s INSTC freight growth alone is expected to double by 2025 and by 2030 triple the volume of Russian exports.

Iran will be able to play a stronger role in the INSTC, and within the world’s transit industry, by completing the Chabahar-Sarakhs railway line. The Chabahar-Sarakhs railway is 1,350 km long and is being implemented in the form of two sections of the Chabahar-Zahedan and Zahedan-Sarakhs railway lines. The Chabahar-Zahedan railway is now over 50% complete, while the Zahedan-Sarakhs railway will be put into operation by the end of the current government’s tenure.

However, Iran is not satisfied with India’s commitment to the development of Chabahar port and is interested in the investment of Russian and Chinese companies in the development of ports in the Chabahar commercial-industrial free zone (CFZ) and the completion of the Chabahar-Zahedan-Sarakhs railway line.

Iran is also trying to accelerate the fulfilment of the obligations of the Indian side to set up equipment in Chabahar, increase the movement of cargo from the Chabahar route, and take steps towards the earlier completion of INSTC. Iran’s current annual income of US$2 billion from INSTC transit is now essentially secured, as the country benefits from the routes 2 million tons of transit capacity.

It is expected that by the full operationalization of the INSTC, Iran will be able to earn about US$20 billion annually from the route. This can partially reduce the country’s dependence on oil revenues.

Additionally, the INSTC means Iranian access to the Russian markets as well as to Central Asia and the Black Sea. It also has the capacity to become a complex and wider network along the Persian Gulf and Africa.

In addition, opportunities for multilateral economic cooperation such as the formation of a tripartite group of India, Iran, and Armenia, the possibility of transporting goods from Russia and Pakistan from Iran, cooperation on the Persian Gulf-Black Sea route, as well as plans for the formation of a member organization, the INSTC will be increasingly beneficial to Tehran.

A decision by Russia, Kazakhstan, Iran, and Turkmenistan to apply a 20% discount in 2023, for using INSTC’s eastern rail routes, the passage of 10 million tons of Russian export cargo through INSTC and reducing transit time during INSTC to about ten days is an additional bonus for Iran. Meanwhile, the opening of the offices of the National Iranian Shipping Company in India, the efforts of Tehran and Moscow to buy and build a ship to carry goods on the middle route of INSTC or Caspian, and better navigation in the Volga-Caspian basin can speed up the completion of three different routes of the INSTC.

Challenges facing Iran in INSTC

The INSTC is a multimodal network of shipping, rail, and road routes. However, thus far, not many goods have been attracted to INSTC and there are some infrastructural problems.

Sanctions against Iran and Russia have created obstacles. Due to the economic restrictions of the West, it is not possible to continue the INSTC route to Helsinki. Iran’s competitors are making heavy investments to activate other corridors. Apart from Turkey’s plans to become a transit hub, some countries are bypassing Iran.

Iraq, with its US$17 billion transit project – the Iraq Development Road (development of railway lines and transit roads from Iraq’s Faw port to Turkey’s Mersin port), is also a competitor to the INSTC.

The increase in tensions between Tehran and Baku, the cooling of Azerbaijan’s relations with India, and the Armenian-Azeri challenges are also obstacles to the western branch of the INSTC. The continuation of technical and infrastructural challenges of the route are also attracting the attention of actors such as India to transit via the Russia Far East, the route to Turkiye, or the East-West Central Corridor.

Technical issues related to railways, facilitation and acceleration of customs procedures, tariffs, digitization, border control procedures, harmonization of customs procedures, and tariff policies of countries also need to be resolved.

Roads are developed in Iran, but most of Iran’s railway lines need to be developed. For growth from 20 to 60 million tons, Iran’s ports have extensive needs for logistics infrastructure and equipment, reconstruction, and expansion of warehouses. Lack of transit wagons and lack of investment, delays in completing projects, and non-completion of railways in some strategic routes are problems for the wider efficiency of INSTC.

Despite significant investments in Iranian ports, the lack of proper and wide connection of rail and road lines to an effective network has kept the capacity low. The small size of the Iranian fleet and the lower speed of cargo ships in the Caspian Sea, the slow speed of cargo unloading and loading operations, the freezing of the Astrakhan port in southern Russia in winter, and so on are obstacles along the middle corridor of the INSTC.

Therefore, establishing the Roro shipping lines in the Caspian Sea (between Iran and Russia), and improving the loading capacity of ships along the Volga River route have become urgent needs. In the eastern route of INSTC, the main problem of the Chabahar-Zahedan-Mashhad-Sarakhs railway axis (capacity of 8.5 million tons per year) is the lack of completion.

The INSTC Vision

All this said, rail transportation along the INSTC increased by more than 40% in the first five months of 2023. Although most of the volume passed through the western route, the growth of exchanges from the middle and eastern routes of INSTC is also promising. Meanwhile, the middle, Caspian corridor is likely to be the center of attention for the main actors.

However, in order to achieve its goals along the INSTC, Tehran has to overcome many obstacles. The future of the North-South International Corridor largely depends on the India-Iran-Russia approach. Strengthening the dimensions of trilateral geo-economic cooperation will make the INSTC more prominent.

The INSTC is still in its early stages and cannot yet compete with the Suez Canal. But it can reach a high percentage of its total traffic by 2030. In the meantime, the development of Iran’s corridor network in the short and medium term and the annual passage of 20-30 million tons of cargo will over time, make Iran a powerful player and a role player in the global economy and transit.

Related Reading