EDRB Says Significant Transport Infrastructure Investment Needed Across Central Asia & Middle Corridor

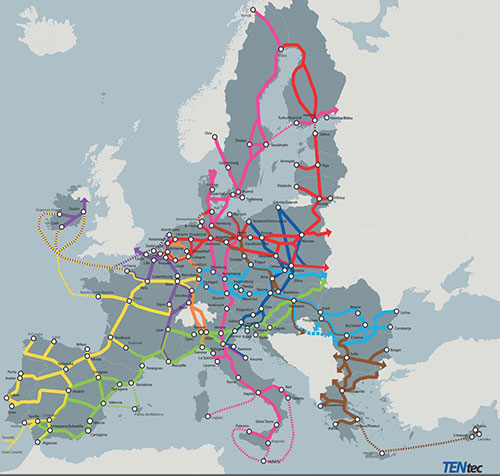

The European Bank for Reconstruction and Development (EBRD) is conducting a study on sustainable transport connections between Central Asia and Europe, funded by the European Commission. The study, which should be completed by summer 2023, aims to identify the most sustainable transport connections between Central Asian economies and the extended Trans-European Transport Network (TEN-T).

TEN-T is a huge transportation network that encompasses much of Europe to the Western borders of Russia and Turkiye. Connecting that further East across the Caucasus, and Central Asia is now a priority given the sanctions imposed upon Russia. This has resulted in trade volumes, particularly container traffic, between Asia and Europe continuing to grow as geopolitical events disrupt existing trade corridors, major trading and logistics companies are exploring ways to diversify and optimise transport routes and make them more sustainable.

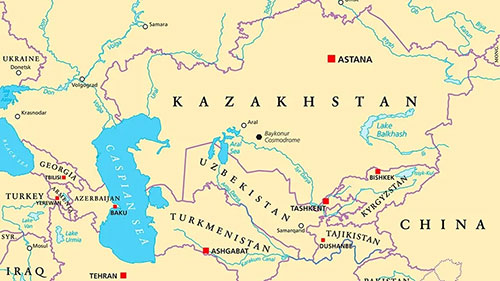

The EDRB study has two objectives: to identify the most sustainable transport corridors connecting the five Central Asian countries – Kazakhstan, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan with the European Union’s TEN-T, including the Caucasus – Georgia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan – and to propose actions for their development, including actual infrastructure investments and the necessary enabling environment. Should this investment be undertaken, it would link the EU to China, overland, without the need to transit Russia. It is the largest study yet undertaken on the scale of China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

The EBRD has presented interim findings of the study:

Northern Corridor

Until early 2022, the main route linking northeast Asia with Europe was the Eurasian Northern Corridor. It used the Trans-Siberian railway from Russia’s Far East, with branches through Kazakhstan and Mongolia. In 2021, it was responsible for transporting around 1.5 million 20-foot equivalent units (TEUs) of cargo or containers. The corridor is operated by the UTLC Eurasian Rail Alliance, owned by Russia, Belarus and Kazakhstan. Sanctions on Russia have diminished its use.

Middle Corridor

The Middle or Trans-Caspian Corridor through Kazakhstan is generally considered the second-best overland option. In Q1 2022, close to 20,000 TEUs travelled through Kazakhstan via its Caspian sea ports of Aqtau and Kuryk. Assuming that demand will continue to rise, the annual volume of freight cargo through the Middle Corridor in 2022 may reach 80,000 TEUs. This is not far from its maximum throughput capacity of 100,000-120,000 TEUs, constrained by a limited number of vessels in the Caspian Sea and non-regular shipment schedules.

Should this corridor become the preferred new route for freight companies, existing Caspian Sea infrastructure may become a real bottleneck. A diversion of transit cargo exceeding 10% of the Northern Corridor’s tonnage will require large investment across the entire corridor and its economic efficiency is yet to be assessed. The EBRD estimates immediate investment needs for Middle Corridor infrastructure upgrades to be in the region of €3.5 billion.

Central Asia

Kazakhstan’s Caspian Sea ports at Aqtau give direct overland access to China and have a developed network with the two Caspian seaports and two railway border crossing points with China. Even so, several large-scale projects are in the pipeline to facilitate east-west trade and transport links, including the rehabilitation and electrification of railway segments, the construction of new railway lines and the expansion of port infrastructure.

The route through Kazakhstan to its ports on the Caspian Sea seems to be most stable option for cargo travelling through Uzbekistan, but there are multiple inefficiencies at border crossing points between the two countries and bottlenecks in the ports at Aqtau and Kuryk. Additionally, the Caspian Sea is not always navigable, so the Uzbek authorities are keen to explore alternatives. Alternative transport connections may incentivize Kazakhstan to improve the quality of commercial services and border management. That implies the EDRB may not be so willing to stump up all the capital requirements.

Uzbekistan is currently pursuing multimodal transportation (road and rail) from China, through Kyrgyzstan then onwards through the Trans-Afghan route or through Turkmenistan and Iran (see also INSTC below).

Uzbekistan is actively developing transport links with all of its neighbours, but as a landlocked country, it will have to rely on transit routes through other countries to present itself as viable transit option. Uzbekistan railways, the country’s main freight carrier, needs to be reformed to improve efficiency. Significant investment will be required to electrify sections of railway in the Fergana Valley, between the key cities of Bukhara and Khiva and elsewhere. The same goes for the rehabilitation of roads across the country. In parallel, Uzbekistan should modernise its rolling stock and improve its customs services to ensure smooth transit and transport. Uzbekistan has a significant trade agreement with the European Union.

Other options include the use of Kazakhstan’s Middle Corridor and the Turkmenistan port of Turkmenbashi. The route through Turkmenbashi, via the Caspian Sea to the port of Poti in Georgia has the highest transit tariff and is barely economically viable. The port is highly inefficient and operates a very limited number of feeder vessels, thus presenting even a bigger bottleneck than the Kazakh ports. Moreover, Turkmenistan is not party to international agreements, and this will require additional bilateral arrangements.

INSTC

The route through Turkmenistan and Iran (INSTC) may eventually become an interesting transportation solution, but there are currently a number of serious limitations. Turkmenistan has complicated sanitary and logistical requirements, on which the country is not willing to negotiate. Neither country is party to international agreements, so arrangements have to be made through bilateral agreements, a lengthy process. Iran is also heavily sanctioned, and it is difficult for European operators to work there unless they have regional subsidiaries that can overcome bottlenecks.

Eventually, the success of the Middle Corridor will depend on the ability of all countries along the route, including Kazakhstan, to work seamlessly, eliminate trade barriers and set up regular and reliable freight schedules. If the Middle Corridor is to become a viable transportation alternative, it must offer a predictable and reliable environment for all parties involved.

Summary

The report raises a number of important questions, not least the European Union’s attitude towards China and Russia. Improved trade and cooperation contacts will be required as both countries maintain significant economic and political influence over Central Asia. That will be difficult to navigate as the EU has heavily sanctioned Russia, while the China CEEC dialogue platform with Eastern Europe has run into regional political difficulties and criticism from Brussels, while the EU suspended up the proposed EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment in 2021.

Nevertheless, dialogue must be held with both China and Russia for the EU’s plans to make any headway, not least because the EU rail network runs on a different gauge to Central Asia, which operates Russian gauge standards. Then there are issues with TIR regulations concerning haulage across the region, which will again attract Russian political and trade interest.

Given that Russian railways are significant investors in Central Asia’s rail network in their own right, and that Armenia, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan are all members of the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union, the EU will have no choice but to involve Moscow in these plans.

China, further away, is also investing significantly in BRI projects across Central Asia and will, over time, wish to see a return on these investments. The EDRB’s plans, while exciting on paper, will still have to include significant engagement with two somewhat trade-ostracised partners to have any hope of future success.

Related Reading