The Future of the Belt and Road Initiative in Afghanistan: Obstacles, Opportunities, and The Taliban’s Perspective

By Farzad Ramezani Bonesh with additional commentary by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China’s goals and opportunities in the Belt and Road in Afghanistan

The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), launched by Beijing in 2013, seeks to connect Asia to Africa and Europe, with the aim of improving regional integration, increasing trade and stimulating economic growth. It also connects China to Southeast Asia, South Asia, Central Asia, Russia, and Europe.

China has also considered Afghanistan’s membership and participation in the BRI with a delegation from Afghanistan participating in its forum in 2017. Afghan delegations have also been participating in Russian economic and trade development forums.

However, despite some agreements in including Afghanistan as part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC), no progress has currently been made regarding China’s economic presence through the BRI in the country.

After the withdrawal of the US and the presence of the Taliban in Afghanistan in August 2021, Beijing has pursued greater economic interaction with the Taliban by expanding economic consultations with its authorities (despite the lack of recognition), strengthening the embassy in Kabul, and accepting the Taliban in Beijing. In fact, China, along with its global thoughts and ideas, its nationalistic, historical, and China’s authoritarian nostalgia, by encouraging the interaction of the international community with the Taliban and canceling economic sanctions, has seen the efficient government in Afghanistan as an essential need to solve the country’s economic challenges.

Most of the Taliban are ethnic Pashtuns, the majority of whom subscribe to the Taliban philosophy and who make up 55% of Afghanistan’s tribal makeup. As Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister pointed out, ‘There is no Government in Afghanistan without the Taliban’. It should be stressed that the current administration is regarded as ‘temporary’ while tribal negotiations can be concluded to assist develop a more unified, rather than an exclusively Taliban administration. However Western sanctions, the freezing of Afghani foreign reserves and a lack of official recognition have not helped in the creation of a unified Afghanistan parliament.

In its foreign policy, Beijing gives priority to economic interests, and although it does not want to undertake unilateral and extensive economic costs in Afghanistan, by taking into account the economic opportunities and threats, it has begun supporting the construction of the Uzbekistan-Pakistan cross-border railway through Afghanistan, and the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan-Afghanistan Corridor Agreement.

Over the past 18 months, China has practically supported the expansion of CPEC to Afghanistan (as part of the BRI). This has become more obvious in the form of China’s positions, including bilateral agreements and declarations with the Taliban, the China-Pakistan agreement, and trilateral agreements between China, Afghanistan, and Pakistan.

In cooperation with Pakistan, China is trying to strengthen its economic position in Afghanistan and expand common interests in the country based on win-win principles.

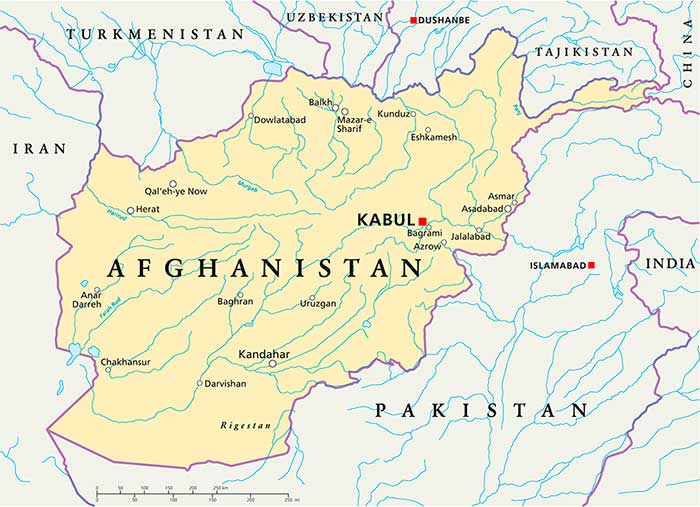

Afghanistan’s joining the BRI means strengthening Pakistan’s transit routes, especially Gwadar Port and the Trans-Afghan ‘Mazar Sharif – Kabul – Peshawar’ corridor. However, this has been hampered by disagreements concerning the Afghanistan-Pakistan Transit Trade Agreement. Trade and transit potential has consequently been reduced as a result.

Under the deal, cargo was sent to Afghanistan through Pakistan’s Gwadar port on the Persian Gulf. However, if the Karachi-Peshawar route can be built near the Afghanistan border and connects Afghanistan to Peshawar, it will benefit the three actors.

In fact, by supporting and guiding Afghanistan to the path of independent development, or showing economic carrots, China seeks to protect its multi-billion-dollar investments and infrastructure projects of the CPEC project in Pakistan.

In other words, Beijing needs Afghanistan’s active support for BRI. On the other hand, according to the long-term memorandum of understanding of the 25-year contract between Iran and China, China considers Afghanistan to be a puzzle connecting the Middle East, Central Asia, and South Asia. Afghanistan’s inclusion in the BRI promises China better access to Central Asia.

China is planning to gradually begin practical work on some lower-cost projects. The first train from the destination of China and from the route of Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan to the inland Hairatan Port across the important Amu Darya River was a step in the implementation of the agreement between Afghanistan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China.

The January 2023 signing of a contract for the extraction of oil from the Amu Darya oil field with China’s regional Xinjiang Central Asia Petroleum and Gas Co (CAPEIC) in an investment worth US$540 million, coupled with a further 200 companies and a wave of Chinese businessmen to Afghanistan are other steps in line with the increasing presence of BRI in Afghanistan. In fact, in the short term, China sees Afghanistan as a potential destination for future long-term investment through its aid to Afghanistan, the opening of a Chinese air corridor, and the exemption of more Afghan products from customs duties.

China is aware of the risks of investing in Afghanistan and sometimes even considers it an economic operational loss; but considers Afghanistan’s natural resources to be a great economic opportunity in the future. Therefore, the extraction of the important Mes Aynak copper mine (the second largest copper mine in the world, 25 km south of Kabul), Afghanistan’s lithium mines and coal reserves are all under commercial and extraction investigation. The lithium found in Afghanistan is a crucial component of large-capacity batteries for electric vehicles and clean-energy storage systems.

It is possible the operations in the Mes Aynak project, itself worth several billion dollars, could start in the late spring of 2023.

The Taliban’s approach to the Belt & Road Initiative in Afghanistan

The Taliban leaders have been trying to get China’s consent for Afghanistan’s inclusion into Beijing’s BRI plans since 2021 and the US and NATO withdrawal from the country. From the Taliban’s point of view, China’s aid is the basis of Afghanistan’s development, while BRI projects can be the gateway to Afghanistan’s redevelopment and re-integration with Central Asia.

Meanwhile, in a 180-degree turn from the 1990s, the Taliban have heavily relied on the economic power of China and the BRI to meet the need for strong and independent financial bases. By expanding the meetings and consultations, the Taliban have proposed many economic opportunities to Beijing in the direction of getting rid of economic challenges, financial stabilization and cutting off foreign aid, reducing the effects of drought, and increasing food insecurity.

There appears to be unity among the Taliban leaders regarding China, they consider China to be the main partner of Afghanistan. In fact, it seems that the Taliban, understanding China’s conditions and power in BRI, Beijing’s strategic relationship with Islamabad, and also the type of its relations with Pakistan, wants to build projects such as the construction of a railway from Torkham to Hairatan; the production of thermal electricity with a capacity of 400 megawatts, and other projects to be implemented.

Obstacles to, and prospects of the BRI in Afghanistan

China knows that sizable project investments need security and stability. The Taliban is still not a legitimate government, has no legal competence as a party to an economic contract and a reliable partner, and does not have a complete monopoly of power.

China’s fears about committing significant resources to Afghanistan, coupled with a lack of water and electricity, and high operational costs are numerous. Apart from the lack of basic infrastructure, friction between Beijing and New Delhi, coupled with weak Taliban governance, means that investing in Afghanistan’s alleged US$1.3 trillion mineral reserves is also risky. (It should be noted not all analysts agree with the potential volumes of these reserves). China knows that establishing security in Afghanistan requires huge costs and major extremist groups such as ISIS can be a significant threat to the Belt and Road in Afghanistan.

In addition, the Taliban’s political opposition does not consider the Taliban government to have any legal capacity due to the lack of national legitimacy and international recognition; and are afraid of negative consequences such as debt for Chinese investments. All these political factors have a negative impact on BRI projects and new infrastructure commitments in Afghanistan.

Afghanistan is also in danger of economic and human collapse. China’s view of Afghanistan is still security-oriented rather than economy-oriented. Although China’s two major mining and energy projects in Afghanistan (the development of Mes Aynak copper mine and oil fields in Amu Darya) have not yet been implemented, the recent contract for oil from the Amu Darya field is the first major investment return to Afghanistan since 2021. China is looking for safer bets in the BRI countries, so Afghanistan does not come to mind as an attractive risk-free destination.

This is especially true in the immediate post-Covid era as numerous capital investments made by China in BRI projects worldwide failed to reach their cashflow generation targets, meaning Beijing is currently focused on debt restructuring and refinancing before embarking on new projects. Getting existing BRI project debt off its books and into a healthier cashflow generating cycle is likely to take until 2026.

This suggests that Beijing is pursuing its Belt and Road Initiative in Afghanistan as a medium-term play. China’s annual commercial and investment engagement in Afghanistan is not yet significant, and until it can be ensured that no damage is done to China, it remains unlikely that further declarations and approaches of the BRI in the country will be implemented – until at least 2026. Then financial risk attitudes may relax somewhat in Beijing and permit a refocusing towards Afghanistan redevelopment and integration. However, China’s approach of testing conditions and increasing its BRI presence in Afghanistan will explore and implement low-risk economic opportunities in the country in the short term.

This article was kindly provided by Farzad Ramezani Bonesh, a Senior Researcher and Analyst about Eurasian regional issues. He may be contacted at frbonesh@gmail.com. Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner of Dezan Shira & Associates

Related Reading