The Case for Leaving the EU and Joining the Eurasian Economic Union

With the Moscow supported Eurasian Economic Union is gaining increasing traction throughout Eurasia and beyond, it is only going to be a matter of time before countries who are currently part of the European Union begin to assess the benefits of changing alliances.

Although membership of the EU comes with membership of NATO – a decision made to “protect” EU nations from Russian military might over fears Moscow could attempt to grab back some of the ex-Soviet states it lost during the break up of the Soviet Union in 1992 – there has been disquiet about the arrangements. Donald Trump has repeatedly stated that EU nations must contribute 2 percent of their GDP to pay for American support through NATO in Europe. Very few nations currently do, a situation that when and if the US President decides needs to be addressed is likely to cause financial friction between the EU and NATO. The EU is supposed to be in compliance with this target by 2024. Trump will be doing his best to make sure that is on track – and especially if he obtains a second term.

This financial burden is additionally sensitive due to Brexit, as the UK is a major funding partner of the EU, representing about 14 percent of the EU’s fiscal revenues. Brussels has already stated that the financial gap is expected to be made up by additional contributions from other EU members. Not surprisingly, this has not gone down well, with five EU members – Austria, Denmark, Finland, Netherlands, and Sweden “refusing” to accept such an increase.

There are also concerns about the viability of the Euro. Several EU countries are not part of the Eurozone and have kept their own currencies. These include Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Denmark, Hungary, Poland, Romania, Sweden, and the UK. Of those, five are ex-Soviet states that joined the EU after 1992.

There are other regional EU issues coming from the bloc’s eastern members, whose make up and history are rather different from the majority of the Western Eurocrats who dominate Brussels. Both Poland and Hungary have current and serious disputes with Brussels over what Warsaw and Budapest see as EU infringement on their national sovereignty. Poland, an EU member, may soon face the unheard of possibility of having sanctions placed upon it by the EU if it does not repeal a recent law giving its government control of the judiciary, including the power to hire and fire judges. Brussels insists upon that right. Poland regards this as an invasion of its sovereignty.

Poland is not the only currently renegade eastern EU member. Hungary was stung by Brussels insistence that it alone monitored and audited bids for a rail link between Budapest and Belgrade, despite the fact that Serbia is not an EU member and EU funds were not being used. Hungary has also been upset by Brussels insisting Budapest follow its line on immigration. The government has submitted a bill making it a criminal offense to “provide assistance” to illegal immigrants. Brussels has again threatened sanctions, again against one of its own members. The Czech Republic has similar issues and is a third eastern EU member being threatened with sanctions. All three nations are being threatened with “Article 7”, which thus far has never been used, but permits sanctions to be imposed on members from advancing policies that threaten democratic institutions. An examination of the Article 7 process can be found here.

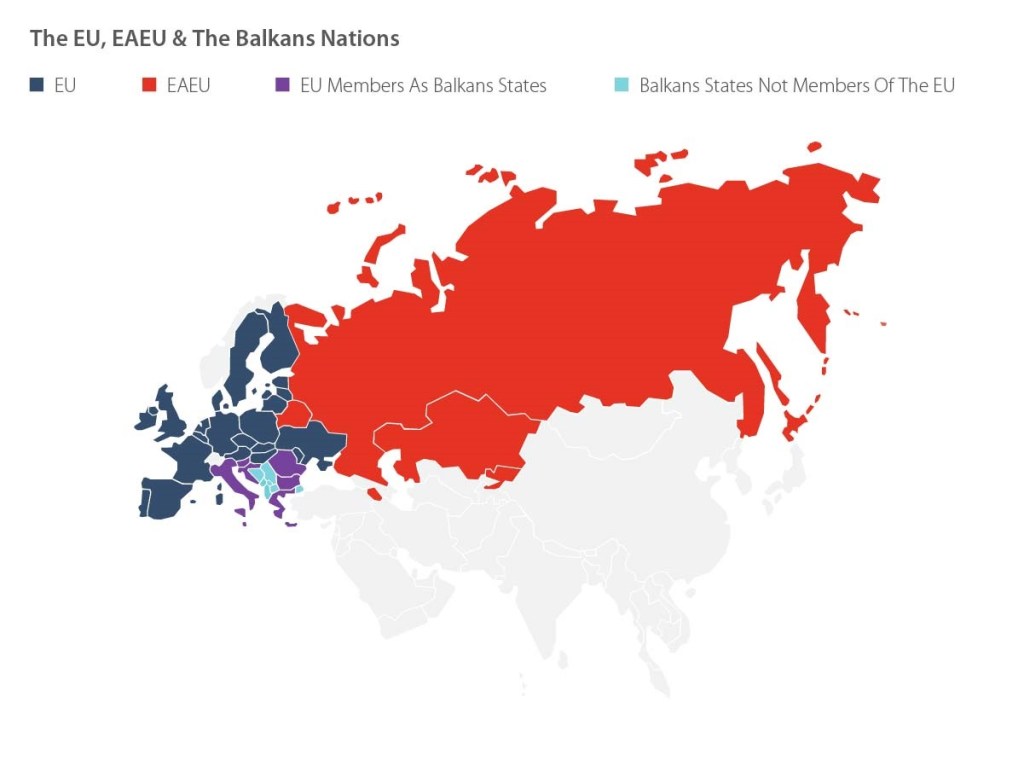

There are other, geographic issues. The Eastern members of the European Union have long borders, relations, and trade with Non-EU members, yet are finding that they are governed by solely EU directives in advancing these relationships, many of which have existed for centuries. This is especially true of the Balkans nations. EU members of the Balkans include Bulgaria, Croatia, Italy, and Greece while the region itself includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kosovo, Northern Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, Slovenia, and the European part of Turkey.

Of those, Albania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Serbia, and Turkey have all applied for membership. Turkey, though, has grown weary of dealing with the EU over this issue, and is instead considering membership of the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU).

The EU itself convened a meeting to discuss the Balkans at a meeting in Sofia last month, after which it promoted “EU connectivity” rather than membership. That meeting was followed by a meeting of the Cooperation Of China & Central European Countries (CEEC) to also discuss China providing finance and infrastructure development assistance in the same region. The CEEC includes Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Bulgaria, Croatia, the Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Montenegro, Poland, Romania, Serbia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. 11 of these are EU members.

It should be noted that with Northern Macedonia and Greece recently making diplomatic peace, there are considerable opportunities along the Belt and Road to reach the Balkans nations through Northern Macedonia. This is especially pertinent given that China owns the majority of the Greek Port of Piraeus, now one of the busiest in the EU.

Russia is also involved in this equation. It is the principal member of the Eurasian Economic Union and shares land borders with EU members Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Norway, and Poland. Belarus, which also borders Russia, is a long term Moscow ally and also borders the EU with Poland.

In terms of the EAEU, it has been extremely active in discussing including both other nations as members and it entering into free trade agreements (FTAs) with other countries. I discussed the Eurasian expansion of the EAEU here.

As can be seen in the map below, should the EAEU follow through with outstanding plans and on-going discussions over membership and FTA, the European Union will effectively find itself surrounded by a massive free trade area to the North, East, and South.

The EAEU has also been successful in areas where the EU has not. It has, for example, signed off an FTA with China. While that agreement is at present non-preferential, it does have the future potential should terms be agreed, to bring Chinese goods right to the borders of the EU. Crucially, other EAEU members would be able to sell, duty free to China. At present this remains a potential; however, with Turkey on board, the situation might become plausible sooner rather than later. Turkey is somewhat in the center of China’s Belt and Road, and is making considerable progress with it’s “Middle Corridor” that facilitates goods trains reaching the EU from China faster than they can by sea, an important issue for perishable consumer items. From Turkey, goods can fan out across Eastern and Southern Europe.

The question the Eastern European Union countries will now be starting to assess is the opportunity the Eurasian Economic Union, coupled with China’s Belt & Road connectivity is beginning to present. That is tied up with the following issues:

- Is membership of NATO good value? Is there an alternative?

- Is membership of the EU good value if financial contributions increase?

- Is the EU imposing unfairly on our sovereignty?

- Is EU trade more valuable than future EAEU and China trade?

- Where does our geophysical and cultural future lie?

There are deeper points to contemplate. One is the view that the current spat with Russia maintained by the EU is devised, in part, to enhance the view of a Russian military menace and to cow EU members into maintaining a strong NATO alliance against it. But is Moscow really such a threat? Spending more on NATO is to the advantage of the United States military and its supporting industries, there remains a vested financial interest by Washington to keep that flow of money coming into the US. But if EU members struggle to meet such demands, what then? Is Russia’s threat real?

Meanwhile, the EU is beating up on its own members and potentially about to impose sanctions upon some of them, while at the same time interfering with members trade and infrastructure development on borders with non EU members. At the same time, those potential EU members are currently being shown a closed door, yet offered “connectivity.” Is this treatment of fellow EU members, with a rather different historical and cultural history to that of Western Europe, entirely justified?

Finally, there is the issue of trade. Economists will have a field day working out the day when the population of the EAEU approaches, in GDP per capita terms, the same as that of the EU. But that’s not necessarily the point. GDP growth requires development and infrastructure opportunities being built. I already discussed how exploiting the infrastructure opportunity was a better strategy than asking for inclusion in development contracts. At the point in time where EU members feel they have better economic potential being part of the EAEU, or having an FTA with it to access China, then you’ll start to see more comparisons being made. At present, that is some time off. But the next decade is going to be very tough for Brussels to emerge from today’s European Union still intact. Meanwhile, Beijing and Moscow will be concentrating on the opportunity angle, rather than conflicts among members, as is the current situation within the EU. Brussels would be wise to think about what it is really wishing for. Does it want to be a free trade bloc or a federal state? Because it is becoming clear not all members wish to be part of a federation ruled from Brussels. The Eurasian Economic Union would then be the only viable regional free trade option.

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm provides risk assessment, business intelligence and professional services throughout Eurasia, and maintains a Belt & Road desk. Please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com

Related Reading:

Related Reading:

![]() New World Order Trade Implications As Putin & Trump To Meet In Helsinki

New World Order Trade Implications As Putin & Trump To Meet In Helsinki

![]() “Here There Be Dragons” How Brussels is Losing Influence in Central and Eastern Europe

“Here There Be Dragons” How Brussels is Losing Influence in Central and Eastern Europe

![]() Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Comes into Focus for EU as G7 Implodes

Shanghai Cooperation Organisation Comes into Focus for EU as G7 Implodes

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.