China: The Great Middle Man Services Developer

The Belt And Road Initiative Moves From Infrastructure Build To Cash Flow Generator

Back in March 2013, I wrote an article ‘China: The Great Infrastructure Developer‘ which described what China was doing as concerns building road, rail, and ports across Asia. That article appeared before the ‘Belt And Road Initiative’ as a specific policy was introduced by Chinese President Xi Jinping – at a speech he made in Kazakstan in September later that year.

Being ahead of the curve when it comes to China is a useful trait. I have a vested interest in seeing our firm, Dezan Shira & Associates, develop across the Asian region, which it has done – mainly because of our ability to spot new trends and new trade and development opportunities. Our clients also have a corporate need to understand where these will be.

Our Asia Briefing series of regional business news also needs such intelligence – we’re building not just an Asian professional investment advisory practice but a daily business newspaper group at the same time – this year, our Asia Briefing subsidiary is on course to achieve ten million readers.

Today though, having observed, and written about the Belt and Road Initiative ever since that March 2013 date – now some seven and a half years ago – I can advise the new longer-term nature of the BRI. It is to insert Chinese businesses, on a global basis, into the middle-man category of service and supply chains. The BRI, while requiring a short-term capital expenditure (often, and incorrectly described as China exporting its excess production capacity) has a specific, strategic financial aim – generating sustainable cashflow.

What China’s Belt and Road Initiative effectively does – and will continue to do – is to insert Chinese businesses into the transportation and transaction costs of global supply chains. The EU for example imports an estimated US$200 billion worth of products every month. Part of the costs of purchasing these, born by the ultimate consumer, involve supply chain and related services expenses that are added to the final point of sale price.

Consider the services required to get those products to the consumer. According to Hellenic Shipping News, in February 2021, the cargo volume of China ports was 1003.5 million tons, a year-on-year increase of 24.4%; while the container throughput of China ports was 18.6million TEU, a year-on-year increase of 35.5%.

Elsewhere, both COSCO and China Merchants Group dominate Chinese overseas port acquisitions. In 2018, COSCO handled 118.8 million TEU at 36 ports worldwide, the equivalent of the combined contained throughput of Shanghai, Singapore, Shenzhen and Ningbo, the world’s four largest ports.

31.7% of this total was managed in overseas ports, the equivalent of Singapore’s annual container traffic. The same year, China Merchants Group handled 20.66 million TEU in its overseas terminals, 18.9% of its total capacity. Because the revenues of terminal business fluctuate less than shipping, COSCO and China Merchants Group should be expected to continue their rapid international expansion.

That’s just Chinese Ports. On a global basis, China has invested in, as part of the Belt and Road Initiative, an estimated 100 ports worldwide.

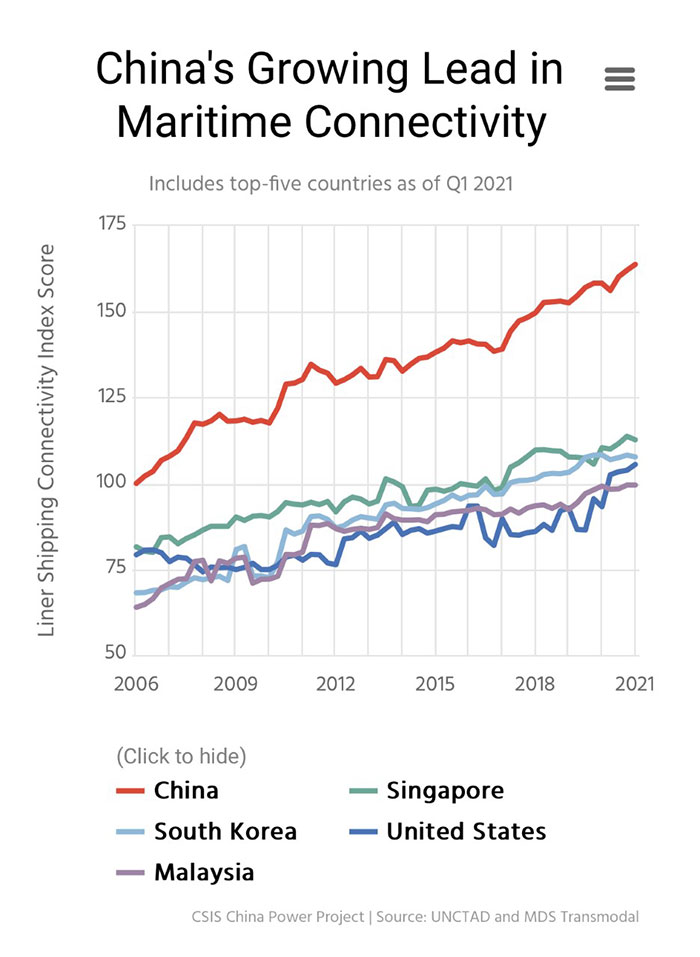

The impact of this is measured by the Liner Shipping Connectivity Index, (LSCI) which measures the effectiveness and global connectivity of Chinese Ports. China’s ranking has rocketed over the years and is now the highest in the world.

Taking the EU as an example, the Chinese owned Ports at Piraeus and Valencia contribute about 10% of shipping volumes into the EU, while Chinese SOE’s own another ten European ports. Others, such as Tallinn, are not Chinese owned but are effectively Chinese influenced by the sheer trade volume they handle. Tallinn is a central European consolidation centre for shipping online purchased products to and from China. Some Estonian workers have no idea their wages are indirectly paid by Beijing.

Interestingly, many of these Port acquisitions are through minority stakes – equity investments. This signals that China is prepared to financially assist with upgrades – but apart from a handful of majority investments – notably Piraeus, Valencia, Zeebrugge and Abu Dhabi, doesn’t specifically wish to be involved with the management. That is a classic business strategy of investing in cash-flow operations.

There are other, non-EU, strategically placed Mediterranean Ports that China also controls, either wholly or in part. These developments include the Suez Canal International Logistics Zone, currently under construction and set to be the world’s largest, and the El Hamdania deep-water Port in Algeria, Africa’s second largest seaport.

These North African developments reveal another strategic, longer-term vision – that under the now-completed African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), China acknowledges that a significantly increasing amount of Eurasian and global productivity will come from Africa. China – and several other Asian countries – have been moving rapidly up the added value chain and are becoming more expensive. That shift is just starting to happen; twenty years from now that migration will be more apparent. China, and to some extent Russia, is reacting to this; both are developing free trade zones and adjacent port facilities to both protect and take advantage of this new trend.

While goods will in future come from a wider variety of sources than China – such as Vietnam, Indonesia, Pakistan, or Egypt – the infrastructure middleman providing the services will be Chinese. It is a great business model – pretty much sustainable cash-flow revenues all the way – and ultimately paid for by European and other global consumers.

That model is being expanded elsewhere – with Port and logistics investments made in the United States (Houston and Miami), the Panama Canal under management by Hong Kong’s Hutchison Whampoa, yet with special attention to the Indian Ocean – trade between Asia, the Middle East, Africa, and Europe. The Northern Sea Passage across the Arctic provides an alternative route to Northern Europe and onto North America, while infrastructure developments elsewhere – and the International North-South Transportation Corridor in particular, only strengthen China’s ambitions in the consumer service sector. The longer-term goal of the BRI therefore becomes apparent – China quietly raking in income via cashflow investments, paid for by the overseas consumer.

Global GDP in 2020 reached USS$85 trillion, of which China’s GDP was about 15 trillion and the United States at about 21 trillion. If China can gain traction of 10% of the total GDP via the provision of services to the global economy, its GDP will rise accordingly. Part of that will be hidden as China’s future business activities will be overseas, not directly appearing on Chinese balance sheets. The implications of this are that China’s share of global GDP is already larger than currently understood, and that its emergence as the world’s largest economy perhaps nearer than previously appreciated – a position achieved solely by China developing its Belt and Road Initiative – with all those cashflow generating businesses hidden within the West’s end user retail pricing.

In this way, China has protected itself from the ultimate fate of increasingly expensive production-based economies and is moving rapidly into services. Sustainable cashflow generation from Belt & Road supply chains, ports and the new digital generation of logistics centres are the way ahead for China to morph into a services driven, global economy, while other emerging economies develop their manufacturing capabilities. It won’t matter in terms of GDP productivity where products are made – Chinese manufacturers are already moving out across the world. There, they will be supported by Chinese supply chains getting product to market. In this way, Beijing will be entirely satisfied with the United States new US$550 billion domestic infrastructure plan because some of that capital will go to imported products – including from US allies – yet brought in by Chinese service lines. China Merchants and so on will take a cut, as they will continue to do – indefinitely.

Until either the United States or EU start to develop a truly global infrastructure strategy that involves investing in and redeveloping a network of Ports, Logistics centres and shipping lines, it is China who will provide the global transportation and logistics services, and the inherent percentage of global cashflow income that will provide.

Related Reading

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com