A Comparison Between Countries & Territories Not In China’s Belt And Road Initiative With Those Who Are

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

Overall Wealth Remains In The West But Future Manufacturing Competitiveness Is Along The Belt And Road

Much of the West’s media attention concerning China’s Belt & Road Initiative is either negative, or about yet another country joining the scheme. Little has been said about the countries and self-governing territories that have not joined up. Yet comparisons between the two are apt – China and Russia have jointly committed to the concept of a “Great Eurasian Partnership” and this has specific consequences for Europe and Asia especially.

The EU is particular is often seen as suspicious towards China’s intentions, hostile towards Russia, yet do not seem to have realized that they have joined forces and are coordinating in increasing terms as concerns the development of the Belt & Road and the Eurasian Economic Union. Brussels views one as Chinese, and the other as Russian and appear to be lost when confronted with joint initiatives that involve or are influenced by both.

An example of this is the recent decision by Serbia, a European country with aspirations to join the EU, changing tack and joining the Eurasian Economic Union instead. With both Albania and North Macedonia having been spurned by the EU last week as concerns previously agreed deadlines for EU membership negotiations, Brussels is playing a dangerous game when it comes to keeping and then breaking promises. The Balkans are very much in Russia’s sphere of influence and it will be interesting to see if these two countries also opt for the Eurasian Economic Union as a viable trade bloc alternative instead, just as nearby Serbia has done.

Brussels seems to view that as Moscow’s influence, but that is only part of the story. China is also poised to complete Free Trade negotiations with the Eurasian Economic Union. Belgrade therefore came to a conclusion that being aligned with China and Russia would provide better future trade opportunities than the EU. But are they right?

Of course the Belt & Road Initiative isn’t only limited to Eurasia. It has expanded into Africa, where both Chinese and Russian companies have been making significant collective inroads. Beijing was largely responsible for the conclusion of the pan-African Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA), which has abolished tariffs on 90% of all intra-African trade – good news if you are selling across multiple African nations or wish to combine African components from different countries into one product. Both China and Russia have been very much aware of this and have stepped up their investments into the region. Interestingly, both countries have invested in their own Free Trade Zones in Egypt – China with a FTZ in the Suez Canal Economic Zone, and Russia in nearby Port Said. These, along with other investments, are having an effect. China-Africa trade is up 3% in 2019, while Russia’s has grown 17%.

While China’s forays into South-East Asia are well known, less understood is the impact Russia is starting to make. Vietnam signed what has become a successful Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union a couple of years ago, and that has seen US$10 billion of Russian capital flow into the country, mainly in the manufacturing sector. Cambodia, Indonesia and Thailand are all discussing EAEU membership while Singapore signed off an FTA last month.

Russia is also following China’s lead in providing debt finance. Russia, in a joint bid with Hungary, has just won a US$1 billion tender to supply Rail Carriages to Egypt’s new high-speed lines, with Russia’s Eximbank loaning the money to Cairo. That is an exact copy of China’s Belt & Road financing.

Increasingly, it seems that what Presidents Putin and Xi said would happen – is. The concept of the Greater Eurasian Partnership is not just here – it is becoming increasingly active. The reasons to expand overseas are many and varied, but essentially run along the lines of wishing to have more control over their respective nations future and their supply chains. Both Beijing and Moscow view the United States as having accumulated too much power, and see an increasing trend of Washington using US trade might as a weapon. President Trump frequently resorts to threatening or using trade sanctions as a form of punishment against governments whose policies run contrary too or are not aligned with those of the US. Beijing and Moscow are seeking to re-establish a more balanced order. But what will a “more balanced order” look like?

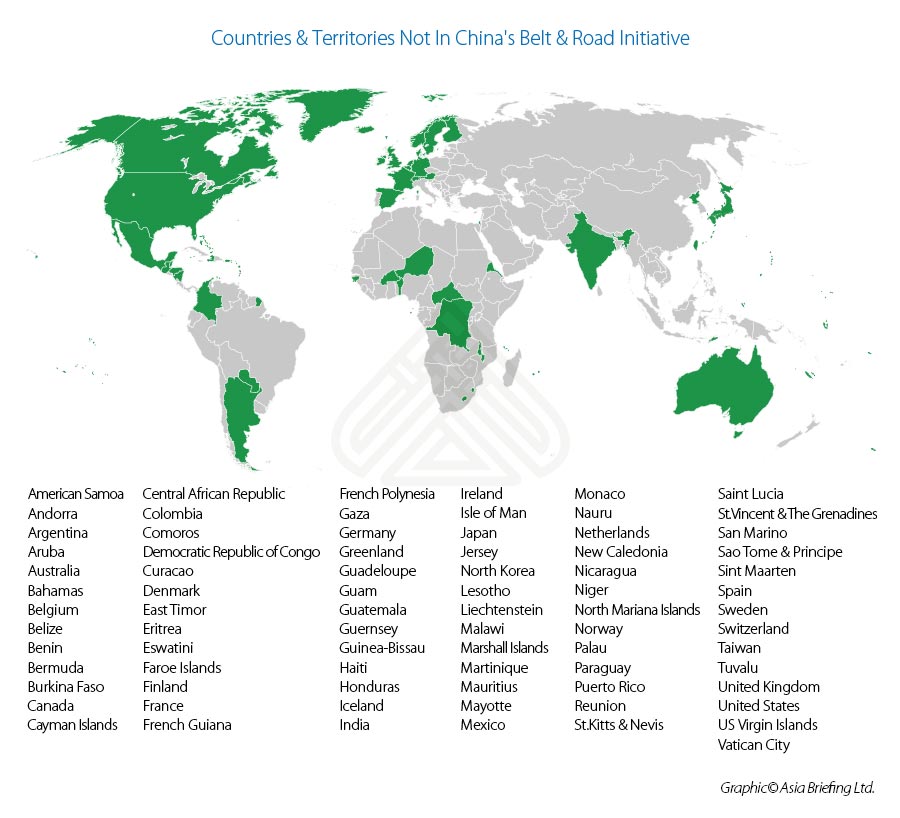

In the map below I provide details of which countries and territories have thus far not signed up to China’s Belt & Road Initiative.

As can be seen, the areas in green remain outside Beijing’s, and to some extent Moscow’s influence. Although there is a lot of green spread around the map however, much of this can be tied to specific countries colonial hangovers as well as existing trade blocs. One could call these, non-BRI members as representing what is commonly referred to as “The Western Powers”. In essence, they include all of North America – Canada, the United States and Mexico, whose binding together under the new USMCA (signed but not yet ratified) free trade agreement limits the ability of Canada and Mexico to enter into certain trade deals elsewhere and specifically with China and Russia. They are aligned almost exclusively with the United States.

The European Union is largely present, although several EU nations such as Estonia, Italy and Malta have signed off on China’s Belt & Road. The UK is there, and also holds sway over certain territories in Africa, South America and to some extent, Australia. France is another colonial power with some territorial influence. In Asia, Japan and India remain aloof from China’s initiatives, Japan as it tends to be somewhat protectionist and India likewise, yet has the additional spanner in the works of on-going border disputes with China. Bar a few Western colonial outposts in Africa and South America, coupled with a handful of tiny island nations, that is the extent of the non Belt & Road boundaries.

Economic Performance Of Non Belt & Road Countries

But how are these nations faring against nations that have signed up to the Belt & Road Initiative? We can broadly categorize them into the United States, Canada, Mexico, Australia, the European Union, Japan and India. These are the economic statistics (courtesy of Country Economics, Trading Economics and the World Bank). All figures are in US dollars and based upon 2019 predictions.

| Country | GDP | GDP Per Capita | GDP Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| United States | 21.4 trillion | 65,112 | 3% |

| Canada | 1.34 trillion | 52,200 | 1.6% |

| Mexico | 1 trillion | 10,400 | 1.2% |

| Australia | 1.1 trillion | 56,748 | 0.5% |

| EU | 18.7 trillion | 36,428 | 0.3% |

| Japan | 4 trillion | 40,487 | 0.7% |

| India | 3 trillion | 2,041 | 6.9% |

As we can see, these economies collectively account for US$50.54 trillion of the estimated US$80.7 trillion global GDP total, with the bulk of that taken up by the United States and the European Union. However, with the exception of the United States and India, GDP growth remains sluggish in these economies. All countries with the exception of India and Mexico, which are emerging economies, have high GDP per capita rates averaging US$39,474 against the global average of US$11,672.

Economic Performance Of Belt & Road Countries

In terms of Belt & Road Countries, we can also break these down into blocs, although given the size and breadth of the BRI this is harder to quantify. However, we can assume that China and ASEAN, together with the Eurasian Economic Union, the Central & Eastern European countries that are members of the BRI, the Gulf Cooperation Council, and much of Africa can be included as representing the bulk of the economies. These figures are as follows, and again measured against 2019 projections and are in US dollars.

| Country/Region | GDP | GDP Per Capita | GDP Growth |

|---|---|---|---|

| China (inc Hong Kong) | 15 trillion | 9,771 | 6.1% |

| ASEAN | 3 trillion | 4,537 | 4.8% |

| GCC | 3.5 trillion | 69,200 | 2.1% |

| EAEU | 1.9 trillion | 10,389 | 4.1% |

| Central & Eastern Europe | 4.5 trillion | 32,395 | 4% |

| Africa | 2.2 trillion | 6,122 | 4% |

Interestingly, of the sample main BRI blocs we have identified, all of them are comparable in size or larger economies than those of the Western bloc with the exception of the US and EU. If the European Union was taken out of the equation, the Belt & Road economies would now be roughly the equivalent of those in the “Rest of the West”. What is noticeable is the disparity in income; with BRI nations with the exception of the petrodollar economies of the GCC and the more advanced economies of Eastern Europe, the bulk have a far lower GDP per capita than the Western economies. But that is also stimulating growth, as manufacturing and cheaper labour supply are seeing BRI economies with significantly higher GDP growth rates than the Western, non-BRI economies. Growth in Central and Eastern European countries is far higher than the current European Union average. However the telling figures are those in ASEAN and Africa, where per capita GDP remains low. These areas also have huge, young and growing populations, and are developing as the future workshops of the world.

What this means is that China, and to a lesser extent Russia, have secured, in diplomatic and to some extent financial terms, the greater influence over much of the global emerging economies – and crucially, those who will be the global manufacturing and production labor force for the next 20-30 years. In this position, it means that China and Russia can grow their own economies by relying on less expensive labor in Asia and Africa. That requires investment and planning – something that both countries have been doing in terms of agreeing with third party countries the development of Free Trade Zones in these same economies and across the Belt & Road in addition to providing finance.

China has taken the lead in this, and established over 80 FTZ in other countries over the past five years. They extend all the way from China’s border right up to the borders with the European Union as well as across South-East Asia and into Africa. Russia is also now starting to follow suit. What this does is give China and Russia access to cheaper labor than is available back home, with the additional benefit for Russian companies being that they can now escape the lower winter productivity downtime the country has traditionally suffered from as temperatures drop below -20 between December – March – a loss of 35% of total annual output. Russian FTZ in places such as Egypt’s Port Said offer year round production capabilities at competitive labor rates. India has also expressed interest in hosting Russian FTZ and this model can be expected to develop further across Africa and Asia.

In previous articles, I have highlighted the emergence of strategically placed Free Trade Zones across the Eurasian land routes of the Belt & Road Initiative, the Free Trade Zones Linking China, Russia And The Eurasian Economic Union as well as Free Trade Zones across Russia itself. However, the fact that both China and Russia are developing FTZ overseas in addition to their internal zones is a relatively new phenomena and one that will develop further still.

It is a quid pro-pro. With interest rates having been historically low for the past few years, China and Russia have been and will loan the money for the infrastructure, take advantage of the lower labor costs, and employ the millions of workers coming of age in Africa and Asia. The Belt & Road nations, via their involvement in already existing or upcoming Free Trade Agreements, will be coming along for the ride.

This is one reason China has established the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank and the BRICS nations the BRICS New Development Bank and Russia the Eurasian Development Bank as it allows these countries to access funding at more favorable rates, when interest rates are already low. Passing that lower cost funding capability onto nations that can only borrow at higher rates is one of the component parts of what China especially and now Russia are doing – despite the howls of protest concerning debt-traps and chequebook diplomacy. The options for BRI countries such as Sri Lanka and Egypt is either to borrow from other institutions at higher rates of interest or not develop their infrastructure needs at all.

It is simple economics. Sri Lanka’s Central Bank has a rating of B. Egypt’s, the same. Yet the AIIB has a credit rating of AAA, the New Development Bank at AA+ and the Eurasian Development Bank at Baa1. These are all higher scores than many of the BRI countries are able to obtain. Borrowing costs less for these institutions than many of the national governments can access, and China and Russia are happy to pass that capability on – for a small mark up, or sometimes none if contracts can be arranged for their domestic companies to participate in the infrastructure build.

The real issue about Chinese and Russian funding is that if there were viable alternatives proposed by the West, the likes of Sri Lanka and Egypt wouldn’t need to borrow from China or Russia. But there aren’t, and both Moscow and Beijing have instead been making sure infrastructure investment capital does get spread around and is more accessible to poorer nations. This is precisely why many of them have signed up to the BRI – they can borrow at lower rates than Western controlled financial institutions are offering.

These are benefits that the European Union and North America are unable to match. Although the American manufacturing industry servicing the United States domestic market is being encouraged, somewhat bluntly, via the US-China Trade War to invest in Mexico – closer to home and more amenable and malleable to Washington than Beijing is, Beijing and Moscow are now taking the future global manufacturing economic bases in rather greater strength and numbers than the US has. The United States, EU, Canada and Australia have also wasted the opportunity of investing their somewhat creaking infrastructure right at the same time that interest rates are low. Instead all of them have been wasting that opportunity to create real longer term wealth by encouraging housing booms for short term political gains.

And that, essentially is the significance of the Belt & Road Initiative – securing not just new supply chains for products China and Russia needs, but also a global network of low cost production facilities from which they can start to develop to appropriate production standards through low-cost financing and improving infrastructure, exert influence – and sell to much of the global supply chain. They will collectively, over time, be more competitive than either the United States or European Union, who will ultimately develop to be customers.

A bell-weather to watch, interestingly enough will be to see how the U.K. behaves Post Brexit. Will it become tied directly to the United States as an economy or will it resist that temptation and seek to get involved in trade deals with the emerging economies that China and Russia have already identified?

In short, what is occurring is a global supply chain dance that appears to be dividing up between the West on one side, and the China-Russia alliance on the other. At this juncture, the latter appear to have sewn up the competitive manufacturing options for the next three decades. Where that will leave the United States, seemingly reliant on Mexico, and the EU, reliant later perhaps upon India for cheap labor resources is something of a question that has not as yet been adequately understood, or answered.

Related Reading

- Free Trade Zones on China’s Belt & Road Initiative: The Eurasian Land Bridge

- Russia’s Eurasian Economic Union Free Trade Area Gets Its First Foothold In Europe

- China’s Maritime Belt Road Free Trade Agreements In South Asia

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written and produced by Dezan Shira & Associates. Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Practice Chairman. The firm advises businesses and governments on Belt & Road Initiative strategies in addition to handling foreign investment throughout Asia. Please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com