The Afghan Commodities The United States & EU Wanted, But China, India And Russia Now Intend To Develop

Afghanistan’s huge mineral wealth and development opportunities are heading East, not West

The underlying reasons for the US and NATO’s operations in Afghanistan, prompted by the faster than expected success of the Taliban taking control were strongly hinted at by the EU High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy Josep Borrell last week, at an unscheduled meeting of the European Parliament committees on foreign affairs. He called to prevent Russia and China “from taking control of the country and becoming “sponsors of Kabul.”

That concern is understandable, as Western entities had already conducted geological and feasibility reports for its companies to insert themselves into Afghanistan’s mineral fields and regional supply chains to extract value. A pro-Western Government in Afghanistan would go along with this. But that hasn’t happened. The question remains though – what specific commodities does Afghanistan have to justify a twenty-year war and billions of dollars in attempted acquisition costs, mainly by funding the military?

Afghanistan is extremely rich in minerals, with about 1,500 commercially viable deposits, including oil, gas, coal, copper, iron, precious and semi-precious stones.

This has long been recognized by respective British, Soviet and American geologists, who understand that if their respective powers could manage to organize some semblance of peace, security and stability, successful operations will simply swim in money. The US has in fact been interfering in Afghanistan for years before the USSR did – being instrumental in supporting the coup that deposed the last Afghan King in 1973 to usher in a more US compliant regime. That in fact destabilized the country and has led to the collapse of a peaceful, relatively modern society into the largely destroyed Afghanistan we see today.

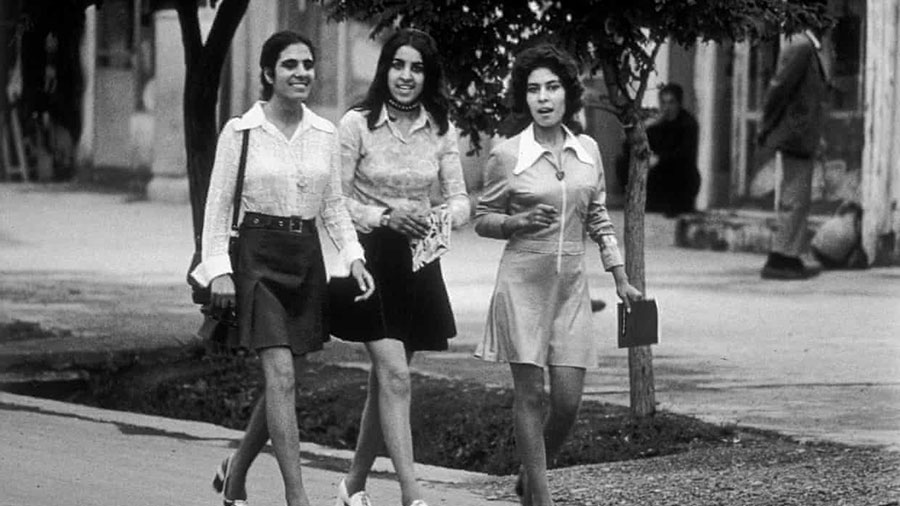

Afghan women in Kabul, 1972

Economic theory claims that energy is the basis of state development in the modern world, and this the key reason why Afghanistan has had to endure such suffering. The Taliban, if they show certain political wisdom, in fact have a chance to go down in history as reformers who pulled Afghanistan out of the Middle Ages. The differences are that while the US and the EU, under the banner of NATO tried to militarily occupy and impose control on Afghanistan, a now more contrite Russia, and Chinese pragmatism recognize that Afghanistan requires a subtler touch – and that much more needs to be left in the ground for Afghanis than the Western nations had considered or were even ever able to deliver. Mining and Energy Companies in the West are overly pressured to deliver ever-increasing profits – a capitalist cycle that spells disaster for the local communities (such as Afghanistan) upon whose land such commodities lie. The Taliban realize this, meaning they are not purely the ill-educated local Pashtun’s that Western media often portrays them to be. Taliban officials have been educated in the Middle East, they know full well the value of the Afghan deposits and understand that Western financial systems and rapacious demands will eventually hollow out Afghanistan and leave it hollowed out.

China, Russia and the rapidly expanding regional grouping of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation know this too. For the West, the game is up. Their Afghan failings can be laid squarely at their over-extended capitalist systems – food for thought for the West, moving ahead in a much changing world. Let us then consider what Afghanistan has in strategic reserves and whose national interests match these assets.

China – Oil, Gas & Lithium

In the northern Afghanistan province of Balkh, along the Oxus River and the border with Uzbekistan and Tajikistan, large reserves of hydrocarbons have been discovered. The US Geological Survey, which conducted field surveys under the protection of the US military, estimated the potential of the basin at 1.8 billion barrels of oil, 440 billion cubic meters of gas and more than 560 thousand barrels of gas condensate. For Afghanistan, which consumes a paltry five thousand barrels of oil per day, this represents extraordinary reserves that can solve the national energy needs for decades to come.

China has its eyes on this. In 2011, Kabul entered into an agreement with the state-owned China National Petroleum Corporation (CNPC). They received a concession for the development of three fields, and in return undertook to build three refineries, which were built within three years. It should be noted that Beijing offered Kabul extremely favorable terms: 70% of the profits from the production and sale of oil and gas were to be remitted to Afghanistan, way more preferable terms than any US or EU companies would be capable of offering for the reasons described earlier.

However, China’s main interest in Afghanistan is lithium. Ten years ago, the same US Geological Survey published data , from which it described that US$3 trillion worth of lithium reserves are available to be mined in the country.

China is the world’s leading manufacturer of electric vehicles and battery technology for which lithium is a key component. It should be noted that just a couple of hours after the Taliban seized the capital, China’s deputy permanent representative to the UN announced that China is counting on “friendly cooperation with Afghanistan.” It is noteworthy that the Chinese Embassy in Kabul was not closed, remains undamaged and is now guarded by armed representatives of the Taliban.

Afghanistan also possesses large quantities of rare earths, and especially cerium, neodymium, lanthanum, zinc, and mercury. Whoever gains a foothold in Afghanistan holds an effective monopoly in the processing and use of rare earth metals.

India – Iron Ore

India has already declared interest in Afghanistan’s huge Hajgak iron ore deposits, whose primary commercial feature is that the ore lies very close to the surface. This allows it to be mined openly with simple excavators. Hajgak contains as estimated 32 kilometers of solid deposits and a gigantic two billion tons of very high-quality iron ore. Geologists have stated that the deposits could even be double the estimated size. Also, the neighboring areas of Shabashak and Dar-l-Suf have industrial sized deposits of coking coal – ideal conditions for metallurgy development.

That combination is perfectly aligned with India’s intentions, with New Delhi previously approving a state program to conquer the world steel market. In 2016, India, Iran, and Afghanistan concluded a trilateral agreement, according to which Delhi invested in the modernization of the Iranian port of Chabahar, while Tehran built a railway line spur from the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) that reached Herat in Afghanistan on its northwestern border.

India planned to invest US$10 billion in the construction of the Hajgak mine and a direct railway to Chabahar. The mining project was stopped due to Afghanistan’s instability, and is now on hold, while the Port is now operational. The mining opportunity remains with the assets still in the ground. India restarted discussions with the Taliban to discuss security and trade earlier this week.

Russia – Gas Infrastructure

Russia’s signature involvement that Moscow traditionally offers to everyone who wants to cooperate with it are the main gas pipelines. In 2010, a quadripartite agreement was signed on the construction of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline. This runs for 1,700 km and has a capacity of 33 billion cubic meters. The construction cost was estimated at US$10 billion, with Russia’s Chelyabinsk Pipe-Rolling Plant winning the tender for the supply of trunk pipes. Progress has been slow, due to the endless instability, fighting and power jostling that was a feature of the US involvement in Afghanistan. It should be noted that the United States also had designs on controlling the TAPI pipeline, build and supplies to be routed to proposed US terminals in Southern Pakistan, destined for US markets and export sales.

Today though, assuming the situation in Afghanistan stabilizes, Russia can be expected to become the main supplier of pipes, provide refining technologies and building local infrastructure to develop an Afghani national grid as well as for developing onward transit to Pakistan – for which Afghanistan receives transit fees.

Despite 20 years of a US and NATO presence in Afghanistan, the country has an enormous shortage of electricity. No supply infrastructure to support the Afghan economy and industrialization was ever put in place – again signaling that the ‘nation-building’ the US politicians stated was going on under their presence in Afghanistan was in fact false.

We can make comparisons. Afghanistan has a population of 38 million, and domestic supplies with a combined installed capacity of 3.1 gigawatts.

Ukraine, which has a population of 44 million, has domestic power generation capabilities of 55 gigawatts. So much for US investment in Afghanistan and nation building. The interest was purely for US interests alone without any thought to Afghanistan infrastructure development – a policy in direct contrast to China’s development of the Belt & Road Initiative.

Russia though has been waiting in the wings. For the past decade, Moscow has been developing an energy bridge between Azerbaijan and Iran, which borders Afghanistan to the West. We have already touched upon the development of the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) between India, Iran, and Russia in my comments above about Indian involvement in Afghanistan.

That means that an expected expansion of the Azerbaijan-Iran gas pipeline could also be expected to lead further east into Afghanistan, again providing much-needed energy and allowing Russian companies the prospect of building the supporting infrastructure.

Afghanistan also has two (outdated) hydroelectric power plants at Darunta and Pul-I-Khumri, while Russia in recent years has gained a wealth of experience both in modernizing its own hydroelectric power plants and building new ones, including small and medium-sized power plants built in difficult high-altitude conditions.

Impact

In these respects, we can learn several things: that in Afghanistan, it will be Russia that takes on the energy infrastructure build – it has more experience than this than China, better technologies, and existing friendly and long-standing relations with other regional key energy suppliers: Azerbaijan, Iran, and Turkmenistan. It will become the dominant energy player in Afghanistan and Central Asia.

China will continue its decoupling from US supplies in products such as semi-conductors as it is about to possess some of the world’s largest supplies of essential minerals. That will speed up the closing of the US-China digital technology gap and see Chinese IT and other new tech developments catch up with Western technologies at an increasingly rapid pace.

India meanwhile has bet on industrialization and a future Asian, if not global demand for steel. Together these three countries will contribute significantly to global supply chains, energy deployment and new tech.

The United States and to some extent the Western powers now face an existential problem. Their structural system of taking profits on an ever-increasing and rapid scale at the expense of all other considerations has been cracked. Had the United States and Europe been more sympathetic to Afghanistan (and other power plays) rather than sending in the military under stealth to secure global reserves, then the likes of the Taliban would not have been so vehement in confronting them. Ultimately, structural deficiencies within the West’s current version of capitalism saw the system beaten. An overhaul is required, although how that is to be accomplished is now tied up in climate change debates. The West must think long and hard about the lessons inflicted upon them in Afghanistan. A good place to start, while China, India and Russia pick up the pieces, is to acknowledge that it was never really a ‘War on Terror’ from the start.

This article contains parts originally written by Sergey Savchuk and previously published in “The Fronter Post”. That article can be viewed here

Related Reading

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com