Renegotiating China Belt And Road Debt

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

- US$28 billion BRI debt currently being negotiated

- Strong possibility of more debt restructuring needed in 2021

- A pragmatic rescheduling policy is apparent

- China Debt Risk is US$1billion for every US$142 billion in BRI assets

As I mentioned in the article China Belt & Road Projects Value Now Exceeds US$4 Trillion the global pandemic coupled with other financial stresses have resulted in about US$94 billion of Belt and Road loans having to be re-negotiated. To put that amount of money into context, this is roughly equivalent to the annual GDP output of countries such as Kenya and Sri Lanka, and rather more than the GDP output of Bulgaria, Myanmar or Uzbekistan.

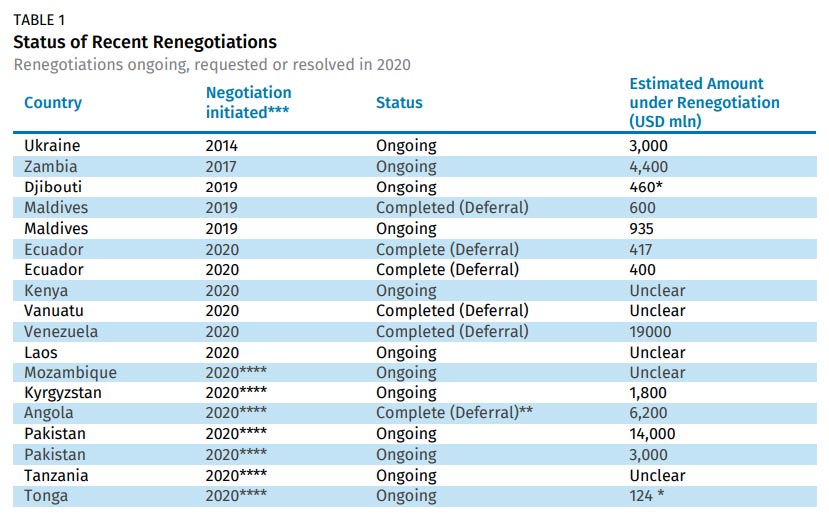

Research from the Rhodium Group suggests that some 15 countries are now trying to renegotiate Belt and Road related project debt with Beijing, with an estimated US$28 billion of the US$94 billion still to be dealt with. As Rhodium suggest, it is hard to be precise about figures and is possibly a lower estimate as debt negotiations are generally handled in strict confidence and it is difficult to obtain full transparency of figures.

These countries are as follows:

How Belt & Road Debt Is Accrued

Corruption

The Maldives Finance Minister Ibrahim Ameer, speaking to the Financial Times at the end of last year shed some light on corruption at Government level from the previous Maldives administration: “The former Government knew what they were doing, getting kick backs from contractors. That’s why the contract prices were too high.”

I have heard similar stories in other Southeast Asian countries, with loan rates being charged by China, typically at a 2% interest rate being renegotiated to 6% interest repayments to be due. That 4% balance is then funneled into secret offshore bank accounts.

China has some culpability here, although not directly introducing corruption does seem privy to permitting it. Beijing notes that BRI loans and terms are provided ‘in accordance with the wishes and needs of the sovereign Government” which is all well and good except when officials within that – often democratically elected Government – are corrupt. One of the drawbacks of democracy is that 4 years terms are often seen as potentially a once in a lifetime opportunity to have access to, and control, huge sums of money. That China has been known to shift financing it must know has corrupt intent from its major banks to smaller regional banks to accommodate and cover up suggests it is aware of the issue and the need to protect its larger institutions from any wrong doing. Yet the result is the same: local economies get ripped off.

Economic Deterioration

The Covid-19 pandemic has had a huge impact on the global and regional economies, just at a time when the Belt and Road Initiative has been providing finance to higher risk, emerging economies. No-one could realistically have predicted Covid-19, although as a prudent businessman myself I would argue that it is always best to maintain reserves, and especially in emerging markets, as one needs to be prepared for the unexpected. Unfortunately, I run a business and not anyone’s country. An interesting sub note as concerns China’s BRI lending is that nearly half of cross-border flows related to China’s Belt and Road Initiative have been directed to regions that are exposed to a significant level of climate change risk. That can be seen in context of China’s recent commitment to reduce net carbon emissions to zero by 2060.

Regardless of competence and ‘bad luck’, the economic deterioration of circumstances impacts on certain Belt and Road loans, and China as banker is called to the table to assist.

Restructuring Belt and Road loans

There are many ways of handling this, but restructuring essentially boils down to three main issues: renegotiating the debt repayment timeframe, renegotiating the interest rates, or swapping debt for equity. It is the latter issue that often proves the most contentious in China’s BRI deals as this can include the provisions of longer land lease terms, or the opening up of national assets such as fisheries, mines and other commodities to Chinese businesses. This is, in its own way indicative of exactly how much Chinese companies are intertwined with the State; they are tools that can and are used to assist with national policies.

A Pragmatic China

Rhodium’s report however does note a pragmatic approach to debt problems by China, in contrast to the often shrill Western media criticisms. Rhodium find that:

- On no occasions has China attempted to seize assets due to default;

- There have been just two instances when Chinese SOEs have purchased equity in troubled investments financed by Chinese loans, Sri Lanka’s Hambantota Port project, and the Electric Grid assets of Laos. This is from a total of an estimated 1,590 BRI projects.

This suggests that while China is amenable to restructuring the repayment terms of problematic loans, this is carried out to ‘tide clients over’ rather than to forgive debt or even to refinance except on very rare occasions.

Corrupt Payments Overseas

As I mentioned above, there does appear to have the facilitation of payments made overseas as part of certain deals. Whether these are made in lump sums upfront, which any corrupt official would presumably prefer, or are staged payments is an interesting point. If payments are to be made over a period of time, what happens when an official loses office and influence, or if the overall project debt needs to be renegotiated? Cutting officials loose after they lose an election may not always be the obvious choice – officials may be re-elected later and that influence required again. All Governments have their ‘fixers’ and China will be no exception in weighing up how to deal with politicians from overseas.

2021 Debt Restructuring To Rise

However, there are still a number of chickens that have to come home to roost. The impact of the pandemic and stresses it has inflicted on numerous emerging, smaller nations with BRI projects may not become fully apparent until the early part of 2021, suggesting that the doors to China’s banking and diplomatic institutions will be rather busy next year. That is also China’s risk in having lent to emerging nations, but it does appear to have in place contingency plans to deal with these issues and a specific debt restructuring policy.

This is good news, as it indicates that China has been prepared for the eventuality. It is also a good sign that China has been able to reschedule US$66 billion of the estimated US$94 billion it has thus far been asked to renegotiate. It is also interesting to note that it rarely seeks to acquire equity in projects in return for debt relief – twice from over 1,500 projects is a very low ratio.

Then there is the percentage of current debt under renegotiation against the value of the Belt & Road projects China has invested in – US$28billion versus US$4 trillion. That means that China’s effective Belt & Road Initiative risk per US$1 billion is hedged against US$142 billion in BRI project assets, and those are pretty healthy risk ratios. Even if the debt renegotiation amount rises during 2021, it seems that China’s ability to finance Belt and Road lending and any restructuring problems it and other nations experience are well under control.

Related Reading

- Belt And Road Initiative Negativity Now In The Past As Debt Trap Burdens Are Debunked And Global Investors Can Look To Opportunity Returns

- How Does China Know Its Belt And Road Initiative Will Work? Because It Tried It Out On Itself First.

- Five 19th Century Infrastructure, Investment & Trade Projects That Belt And Road Initiative Critics Should Be Aware Of

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com