Five 19th Century Infrastructure, Investment & Trade Projects That Belt And Road Initiative Critics Should Be Aware Of

- Think that empire building, militarization, debt burdens, forced labor, bribery, corruption, biased judiciary, unfair land use rights, and basic denial of human rights are new phenomena ? Think again…

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China’s Belt and Road Initiative has come in for huge criticism in the West, with accusations of dubious motives and behavior ranging from Empire building, militarization, debt burdens, forced labor, bribery, corruption, biased judiciary, unfair land use rights, denial of human rights and a whole array of other criticisms. The European Union regards it as ‘splittist’ in terms of its projects on the EU’s own borders. The list of perceived problems with the Belt & Road Initiative can keep a committed critic engaged for hours and probably several weeks. I previously wrote about the onslaught of anti-BRI rhetoric in the article: The Belt And Road. China’s Most Internationally Divisive Campaign Of The Past 25 Years.

Yet these problems – and when real are extremely serious concerns – are nothing new. In this article I describe five major infrastructure and investment projects carried out in the 19th century when the Great Powers were Empire building themselves. Government and civil corruption, bribery, slavery, disregard of basic human rights, theft, excessive forcing of unfair trade terms, military threats and even war were carried out on other nations sovereign territories.

Today, while China does make mistakes, and corruption seeps into deals just as it always has, there are more checks and balances and limits on what activities a foreign country can engage in before being called to explain their actions. Bodies such as the United Nations and WTO can discourage mercenary behavior, prosecute, mete out justice, and provide punishment. Sanctions, although often now tainted by vested interests, can be inflicted, and it is far harder today than it was back in the 19th century to get away with nefarious behavior. But perhaps before criticizing China’s Belt & Road Initiative, it may be useful to look back at recent history and contemplate how then and now are actually rather different periods. China’s Belt And Road Initiative, for all its faults, is being run on rather fairer conditions than these following infrastructure and investment projects ever were.

Sugar Plantations, Caribbean

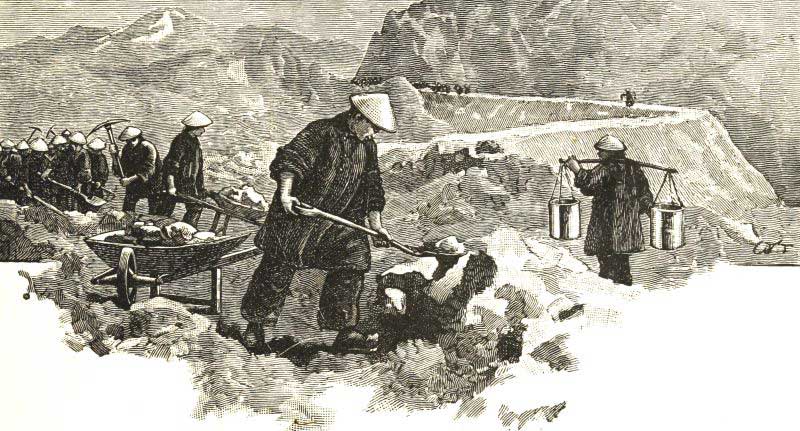

In 1842, the British negotiated the Treaty of Nanking with the Chinese Government, which opened up five ‘Treaty Ports’, permitting the British to trade in what is now Guangzhou, Xiamen, Fuzhou, Ningbo and Shanghai. This treaty was signed off after Britain and China had gone to war over the British opium trade in China, an unwanted commodity forced upon the Chinese by British warships and cannon fire. However, although the Treaty was used to enhance trade and open up China, it was also used in these specific ports to recruit Chinese labor, sometimes under duress (hence the term “shanghai’d”). This labor was then shipped to the Caribbean and South America to work on sugar and other plantations. Foreign merchants took advantage of the British terms imposed on China after the Treaty was signed, to broker deals for “contracted” workers. In 1847, two ships from Cuba transported workers to Havana to work in the sugar cane fields from the port of Xiamen. The trade soon spread to other ports in the Treaty, and demand became particularly strong in Peru for workers in the silver mines and the guano collecting industry.

Australia began importing Chinese workers in 1848, and the United States began using them in 1865 on the First Transcontinental Railroad, of which more later. These workers were deceived about their terms of employment and consequently, there was a high level of Chinese emigration during this period. People thought they were going to get rich, families left behind hopeful and excited about a successful eventual return of their prodigal sons and daughters.

However, mortality rates alone during these journeys were very high; it is estimated that from 1847 to 1859, the average mortality rate for Chinese workers aboard ships to Cuba was 15.2 percent, and losses among those aboard ships to Peru were as high as 40 percent in the 1850s, and 30.44 percent from 1860 to 1863. Some of these were Chinese women kidnapped to be sex slaves under the demand of American and Caribbean plantation owners. The recruited laborers were required to pay for their ship fares from earnings which were frequently below living expenses, forcing them into virtual slavery. They were also branded on their backs like livestock to identify ownership and prevent escape.

These workers were actually part of the slave trade, they were sold and were taken to work in plantations or mines with very poor living and working conditions. The duration of a contract was typically five to eight years, but many did not live out their term of service due to hard labor and mistreatment. Survivors were often forced to remain in servitude beyond the contracted period. Those who worked on the sugar plantations in Cuba and in the guano beds of Peru were treated brutally. Seventy-five percent of the Chinese workers in Cuba died before fulfilling their contracts. More than two-thirds of the Chinese who arrived in Peru between 1849 and 1874 died within the contract period. In 1860 it was calculated that of the 4,000 coolies brought to Peru since the trade began, not one had survived.

In the meantime, Cuba’s sugar production increased from 55,000 tons in 1820 to almost one million tons in 1895 to become the world’s largest exporter. The world’s largest sugar traders between 1820 and 1890 were Britain and the United States. Cuban-US trade alone was worth about US$2 billion per annum. The Chinese workers sent there on a promise of wealth meanwhile and largely responsible for the actual work were often paid less than a dollar a week. Today, British-owned Tate & Lyle sugar merchants reports an expected 2020 annual turnover of US$3.72 billion.

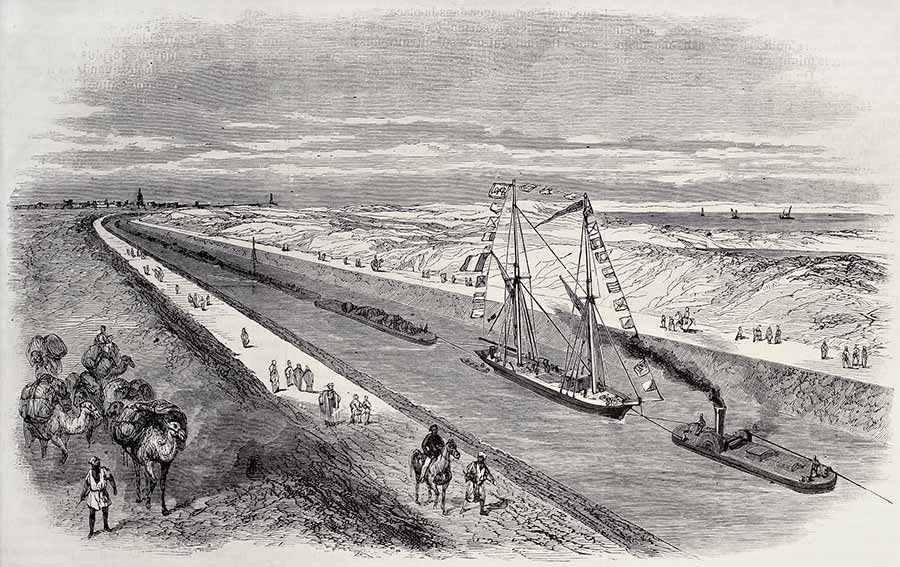

The Suez Canal, Egypt

Work on the Suez canal began in 1859 and took ten years to complete. French nationals were the majority shareholders, with the Egyptian monarchy and wealthy businessmen holding a 44% balance. Local Egyptian forced labor was used to build the canal. Arguments over development costs between the two parties in 1863 lead to French Government arbitration, and promptly issuing the equivalent of what would today be a US$462 million penalty upon the Egyptian shareholders. In 1875, the financial strains this imposed upon the Egyptians resulted in them selling their shares to the British for the equivalent of US$505 million. This business, the Suez Canal Company, then operated the canal as a concession without Egyptian interest for 87 years, when it was nationalized by Egyptian Prime Minister Nassar in 1956, leading to the Suez crisis and a short war between Egypt, France and Britain over the canal. The British and French Governments sent in troops as violence escalated, and Israel also became involved, hoping to gain land from Egyptian territory. British and French foreign nationals, regardless of their situation, were expelled from the country and given seven days to leave. During the Suez crisis about 3,000 British, French, Israeli and Egyptian soldiers died along with about 1,000 Egyptian civilians. About 4,000 civilians were wounded. Egypt with the assistance of Russian support eventually prevailed in the struggle over what was, after all a canal on Egyptian sovereign territory, operating as a commercial venture, following intervention by the United Nations. Loss of compensation to British and French shareholders over operating rights was still sought, and eventually agreed, finally being settled in 1962. Egypt has operated the Suez canal ever since.

The First Trans-Continental Railway, United States

The Trans-Continental Railway began construction in 1863 and was completed six years later in 1869, connecting Iowa on the Pacific Coast with San Francisco. The rail line was built by three private companies, including Union Pacific, over public lands provided by extensive US land grants, while construction was financed by both state and US government subsidy bonds as well as by company issued mortgage bonds. However, vested interests reared their heads and Union Pacific investors manipulated the financing and government subsidies. A fraudulent company, with a specifically non-American name “Crédit Mobilier”, was created by Union Pacific executives to greatly inflate construction costs. Though the railroad cost only US$50 million to build, Crédit Mobilier billed the US Government US$94 million and Union Pacific executives pocketed the excess US$44 million. Then, part of the excess cash and US$9 million in discounted stock was used to bribe several Washington politicians for laws, funding, and regulatory rulings favorable to the Union Pacific directors and shareholders.

The Central Pacific Railway, part of the three private companies contracted to build the route, imported Chinese labor, mainly from Guangdong Province. Many had been impacted by the Chinese Taiping Rebellion and were promised lucrative wages and jobs. These were joined by existing Chinese who had been working in the Californian gold mines. However, once on site they were corralled in little more than tents and controlled by de facto ‘Snakeheads’ or Chinese triads who acted as middlemen between the US employers and the Chinese laborers and reported (in English language) to American supervisors. Money allocated by Central Pacific for wages was siphoned off by both. An estimated 15-20,000 Chinese were employed, accounting for 90% of the entire workforce, while hundreds died from explosions, landslides, accidents and disease.

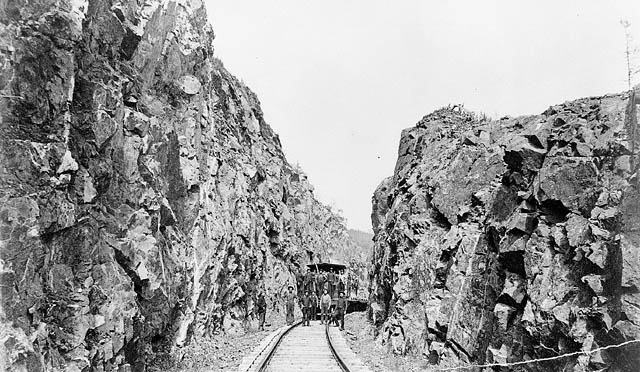

The Canadian Pacific Railway, Canada

The Canadian Pacific Railway began construction in 1881 and was intended to link Eastern Canada with British Colombia, as well as to interconnect with existing track. Funding was raised in Canada, the United States and the United Kingdom. Political differences emerged over routing and collusion with preferred rail connections to the US, with an independent enquiry into financing revealing that 150 members of the Canadian Government had accepted American bribes to vote for particular routes involving vested interests. The ensuing scandal toppled the Government and lead to the resignation of the Canadian Prime Minister.

Meanwhile, 15,000 Chinese laborers were shipped in from China to build the route from the Canadian West coast. Chinese workers were paid CA$1.00 a day, and from this CA$1.00, they had to pay for their food and gear. White workers were paid CA$1.50 to CA$2.50 per day and did not have to pay for provisions. As well as being paid less, Chinese workers were given the most dangerous tasks, such as handling the explosives used to break up solid rock. Due to the conditions they faced, an estimated 600 Chinese workers died from accidents, winter cold, illness and malnutrition. The route is now part of the Canadian National Rail Network.

The Panama Canal, Panama

Work began on the Panama Canal in 1881, with France leading the way, however the project went bankrupt in 1889 after reportedly spending US$287 million; an estimated 22,000 men died from disease and accidents, and the savings of 800,000 investors were lost.

In 1894, a second French company, the Compagnie Nouvelle du Canal de Panama, was created to take over the project. A minimal workforce of a few thousand people was employed primarily to comply with the terms of the Colombian Panama Canal concession, and to maintain the existing excavation and equipment in salable condition. The company sought a buyer for these assets, with an asking price of US$109 million. In the meantime, they continued with enough activity to maintain their franchise. In 1903 during the Panama-Colombia war, which resulted in Panama becoming an independent nation, the United States Navy sent in warships to block the Canal, and subsequently took over the project in 1904 paying US$40 million for the rights. It was completed ten years later and was solely operated by the US on a lease that was agreed ‘in perpetuity’. Almost immediately, the treaty was condemned by many Panamanians as an infringement on their country’s new national sovereignty. The United States imported 75,000 workers, mainly from the Afro-Caribbean, to work on the project, of which an estimated 28,000 died. The United States subsequently ran the Panama Canal concession for 85 years, with operating terms fixed at US$250,000 per annum paid to Panama for the rights. Control of the canal and revenues were eventually passed to Panama as the sovereign nation in 1999 after 22 years of negotiations. The Panama canal is now operated by Hutchison Whampoa from Hong Kong.

Then & Now

Another point to be aware of is that when these huge projects involve a great deal of money, this always leads to temptation and corruption. This exists in both basic and complex forms. A point to remember is that later, when these projects have been completed or otherwise, the opportunity for this type of behavior decreases. What is then left as opportunities are either unfairly long periods of contractual commitment: such as the United States inflicted upon Panama, the British and French upon the Egyptians, or what Belt and Road critics call unfair terms on Ports ceded to Chinese management in Sri Lanka. In truth, moral guidance from any nation over the past 200 years has been perfunctory at best. It smacks of the old adage “Don’t do what I do, do what I say” and it is hardly an attitude of any maturity that China is going to pay any attention to.

There is one final issue. Despite the obvious and highly dubious issues surrounding the 5 projects described above, and no doubt some of the BRI projects too, does anyone really care about these issues once they are built or who built them?

They don’t.

Which is why the greatest way to understand, and perhaps even appreciate and certainly make money from China’s Belt and Road Initiative is to exploit the infrastructure – and use it.

Related Reading

- China’s Belt and Road Initiative – It’s about the Trade Opportunity, Stupid

- Belt And Road Initiative Negativity Now In The Past As Debt Trap Burdens Are Debunked And Global Investors Can Look To Opportunity Returns

- How Does China Know Its Belt And Road Initiative Will Work? Because It Tried It Out On Itself First.

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com