Intra-BRICS 2022 trade

By Contantin Duhamel

With the BRICS nations in the news due to a considerable planned expansion of the bloc by another 13 nations, we look at the current intra-BRICS trade.

What are the BRICS?

The BRICS are an informal grouping of states initially encompassing just Brazil, Russia, India and China (referred to as BRIC) and adding South Africa in 2010. They are not a trade block, nor a geographical or geopolitical entity. Instead, this informal group was originally referred to as countries capable of acting as a counterweight to the global North by developing common positions on global affairs.

An increasingly formal organisation.

Just as other informal groupings like the G7, the BRICS has been taking on an increasingly institutional role. Most notably, the IMF and World Bank are all considered US-centric institutions and the BRICS have tried to propose its own version of a “lender of last resort” for states. Emblematic of the BRICS’ cooperation is the New Development Bank (NDB), whose share capital is equally distributed between BRICS member states.

The desire for a more multipolar world.

Beyond just trade, the BRICS are rooted in the steadfast political belief that a multipolar world is a better guarantee of their interests than one where unipolar (US) interests dominate. In 2021, the countries adopted the BRICS Joint Statement on Strengthening and Reforming the Multilateral System, that inter alia called on reform of the current UN Security Council system. All BRICS countries seek a more balanced and nuanced picture of our world order, though the countries’ interests are far from concurring on every aspect.

Fig. 1 BRICS member countries (highlighted in blue).

Strategic partnership with different priorities.

The BRICS are a very diverse group geographically, geopolitically (see Fig. 1) and from the point of view of political economy. To start with, China is a socialist economy that has generated spectacular growth as it has adopted market mechanisms – while India is a democratic country with a market economy, albeit with certain peculiarities. Crucially, they share a disputed border. Russia and Brazil are decried as stagnant economies, while South Africa is not considered especially dynamic: the BRICS yearn for new life to be breathed into them less be referred to as a front for China’s ambitions.

A “New Era for Global Development”?

To that end, BRICS countries’ delegations met at the 2022 Beijing BRICS Summit. The main point of focus was affirming “support for broadening and strengthening the participation of emerging markets and developing countries (EMDCs) in …international economic decision-making” as well as the G20 as the preferred forum for politics and trade.

BRICS Outreach / BRICS Plus cooperation.

The 2022 meeting confirmed that the BRICS Outreach would now feed into BRICS Plus to push BRICS and EMDCs to closer cooperation and transform the organisation into an “international platform dedicated to improve global economic standards for trade, investment and government through technology and innovations”. In parallel, the NDB is developing with the addition of several new member states.

Fig. 2 New member countries of the NDB, as of 2021e

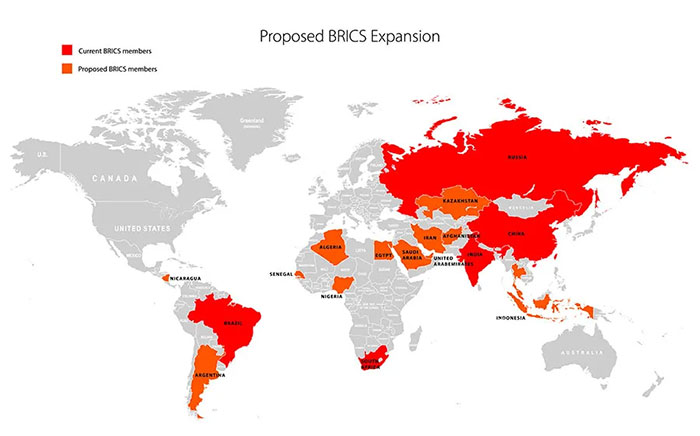

Thirteen other countries have also asked to officially join the BRICS, such as recent G20 host Indonesia– something already covered by Dezan Shira & Associates in their Silk Road Briefing publication here.

Trade in goods

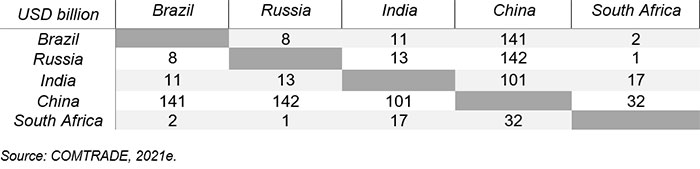

Fig.3 Most recent BRICS trade turnover statistics

China uncontestably leads trade amongst the group.

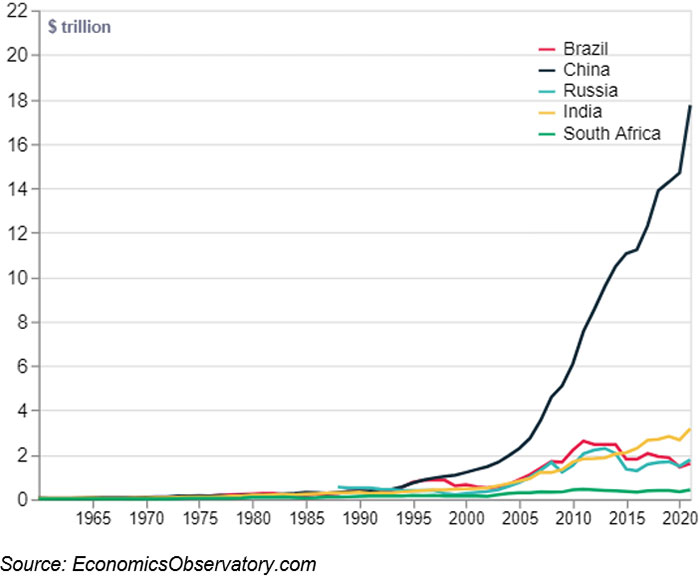

With over USD100 billion in trade with 3 of 4 possible countries in the BRICS and a turnover of USD416 billion, China’s primacy in terms of trade is undisputable. All other BRICS countries’ trade combined represents only just over 10% of China’s trade – at least in dollar terms. This is the result of China’s own economic preponderance and staggering growth rate (see Fig. 4).

China-BRICS trade continues to rise.

According to the Chinese government, “China’s foreign trade with other BRICS countries soared by 12.1 percent year-on-year [USD 195.71 billion] in the first five months of this year, about 3.8 percentage points higher than the overall growth rate of China’s foreign trade during the same period.”

Fig. 4 GDP by BRICS country (2000-21), current USD

Russia’s influence remains evident.

Interestingly, the most active trade player within the BRICS and outside China is Russia, raking a turnover of USD164 billion. This is likely explained by the fact the BRICS are largely an energy-hungry group – with over 40% of the world’s population – and net energy exporters are therefore well positioned. Russia derives its leverage precisely as an energy producer for the BRICS.

India strikes a balance.

India recorded a solid USD142 billion in intra-BRICS trade, though its trade results are far more balanced than Russia’s – trading almost equally with all members bar China and South Africa in particular, where there is an important Indian diaspora.

Has Brazil turned eastwards?

Defying perhaps a more geographical point of view, Brazil’s intra-BRICS trade is firmly oriented towards Asia (China and India) rather than with Africa (in relatively close proximity) or Russia (a similarly-sized economy). This is a testament to Asia’s importance in South America and, without surprise, China’s in particular.

South Africa trade is worth noting.

Albeit the lightest economy in the BRICS, India-South Africa trade and China-South Africa trade is higher than trade between traditional partners India and Russia or Russia and Brazil – showing that is presence with the BRICS is more than just show.

Joint Investment Projects

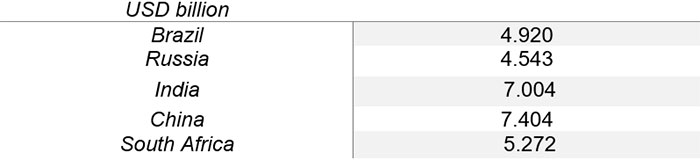

Fig. 5 Size of NDB Investment Portfolio, by country

NDB is Bullish on South Africa.

Rather evenly spread and in lock-step with the respective GDPs of BRICS member countries, the NDB investment portfolio nonetheless privileges South Africa, likely on account of its more numerous market failures – but that the NDB seems confident in turning into opportunity.

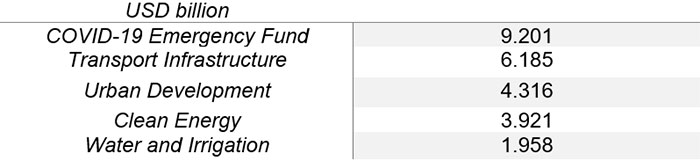

Fig. 6 Size of NDB Investment Portfolio, by type of project

USD9 billion invested to counter COVID-19.

The NDB also provided a facility of USD9.2 billion to finance BRICS government response to COVID which proved key to India and Russia. As the size of this portfolio far outweighs others’ – even on infrastructure – is it possible to say that like with the EU, COVID has pushed BRICS cooperation to a new level.

Development and Growth a clear priority.

Infrastructure and development projects rather than green ones appear to be the priority for BRICS countries – which is logical considering (i) their low carbon footprint from the historical perspective when compared with the West, and (ii) the fact there is still an economic gap they are trying to close with Developed Countries, the abandonment of which cannot be part of any political mandate of BRICS governments.

Investment in water will be a mainstay.

The equivalent to 50% of the funds spent on Clean Energy will be spent on water-related projects, demonstrating it is here to stay as an investment direction. Lack of water is already and issue in Central Asia (Aral Sea, Tajikistan-Kyrgyzstan conflict) and Africa (Ethiopia Nile Dam) and BRICS countries appear very much aware of this.

Joint investment to come for Russia and China.

As of September 2022, Russia and China discussed joint projects and agreed to finance them to the tune of USD1.3 billion. According to the BRICS TV channel, the sectors in question include the infrastructure, pharmaceutical, computer and office equipment sectors.

Future Growth & Development.

The potential admission of the 13 countries that according to Sergey Lavrov, the Russian Foreign Minister that have officially applied to join the BRICS will undoubtedly be a significant, and global trade game-changer. These countries include Afghanistan, crucial as a Central Asian trade hub and vital for maintaining regional security, Algeria, a significant gas resource, Argentina, the second largest economy in Latin America and a major food producer, Egypt, also a significant food and energy producer and a major MENA and Islamic influencer, Indonesia, a key member of ASEAN and a trillion-dollar economy in its own right, Iran, in possession of the world’s largest energy reserves, Kazakhstan, another significant energy play and a vital overland connection between East & West, Nicaragua, in possession of some of the world’s largest gold and mineral reserves, Nigeria, the largest energy producer in Africa, Saudi Arabia, in possession of significant volumes of oil and gas, Senegal, where as yet largely up-tapped, but important gas reserves have recently been discovered, Thailand, another major ASEAN economy, and the UAE, among the world’s largest oil and gas producers. If accepted, the new proposed BRICS members would create an entity with a GDP 30% larger than the United States, over 50% of the global population and in control of 60% of global gas reserves.

Trade vs Security.

There has been speculation that the BRICS could become a threat to the United States and NATO, with NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept viewing 75% of current BRICS members as security concerns. Key here is that this is a reference to specific BRICS members rather than the bloc as a whole, although the nature of the analysis is designed to provoke. However, given that the BRICS has always been a lose trade bloc, we view this position as being unlikely, although this position could change if future intra-BRICS trade imposed upon US energy and agricultural needs.

More likely a concern to the United States and NATO is the development of Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) which is also a regional trade bloc but also maintains a significant security component. The SCO came into being to originally provide military and security contingency plans concerning unrest in Afghanistan, since the withdrawal of the US military from the country it has become more prominent in providing security and, in line with China’s BRI plans, infrastructure development. With the expansion of the SCO also including the Middle East and many potential BRICS members, some alliance between the two is inevitable, however it remains the SCO that has a security mandate and not the BRICS grouping per se.

Constantin Duhamel is an analyst covering Eurasia. He may be contacted at 3cduhamel@gmail.com Additional commentary by Chris Devonshire-Ellis.

Related Reading