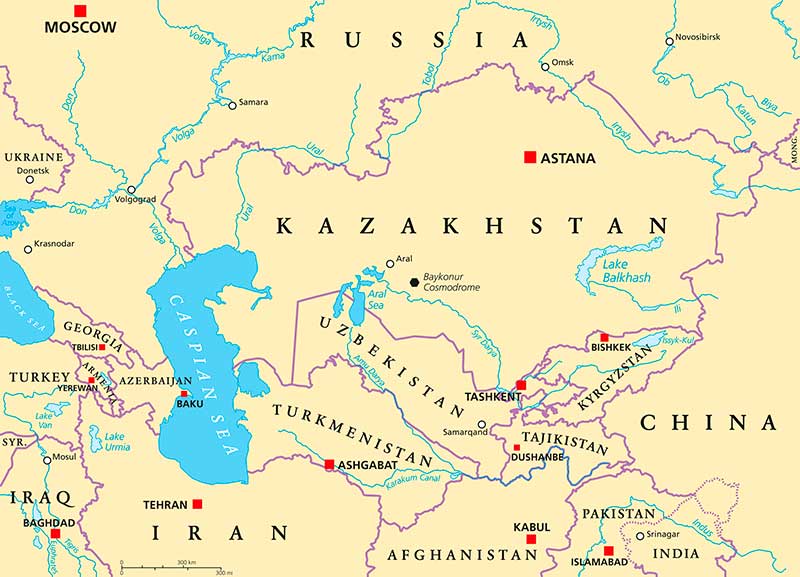

European-Asian Geopolitics – The Implications Of Shifting Supply Chains In Wake Of The Russia-Ukraine Conflict. Part Three: Kazakhstan To China

Aqtau Port City, Kazakhstan

Examining European Union-Central Asian market potential and new supply chain routes through to China via Kazakhstan as new EU-Central Asian trade agreements take effect

The Russia-Ukraine conflict is imposing significant changes on global geopolitics and is re-arranging the Eurasian political and supply chain map with considerable impact. In this article I examine the key areas that will be subject to significant alterations that EU trade with China.

As I explained in Part One, the prospects of any re-emergence of EU-Russia trade in any format looks extremely dim. The conflict has also shuttered Asian access to European markets via Russia, meaning that supply chains are moving south. Although there is an existing route between Asia and Europe via the Suez Canal, the shipping costs and delivery times are greater than an alternative routes via the Caspian Sea. This however requires multi-modal solutions and far greater regional cooperation between participating countries. In Part Two I discussed the INSTC route from Azerbaijan’s Baku Port south via Iran, and in this article, I discuss routes to China via Kazakhstan and related spin off import-export trade opportunities.

Azerbaijan to Kazakhstan

As I discussed in the previous article in this series, the routes from Europe to Azerbaijan’s Baku port are relatively clear cut, although there are rail freight bottleneck issues to be resolved in both Georgia and Turkey. Global shipping and port services businesses are also spending billions on upgrading port facilities and capacity in both. While still not perfect, within the next couple of years the majority of transit logistics problems will be solved.

Baku is emerging as a key Port long the EU-Asia supply chain routes, and with the demise of the EU-Russia rail freight supply chains, is a vital cog in the trade arsenal. However, potential political difficulties remain. Azerbaijan is Muslim and has close relations with Turkey as its larger and more powerful neighbor, yet EU-Turkish ambitions do not always match, in scenarios likely to influence Azeri thinking. A poor corruption index ranking (128 out of 178) a lack of democracy – Azerbaijan was categorized as a Consolidated Authoritarian regime, Azerbaijan receives a Democracy Percentage of 1 out of 100 by Freedom House in 2022, and a dearth of Human Rights standards mean Azerbaijan is not totally suited to be an EU partner. Given that Muslim sensitivities in the EU itself are starting to rise, handling Azerbaijan from the European perspective will be tough. There is plenty of potential for EU-Azeri trade conflict and especially if the EU starts to impose Western style conditions on trade. Frankly speaking, it is an issue that Brussels cannot really afford.

That said, the EU as a collective is Azerbaijan’s largest trade partner, with about 36.7% of all Azeri trade. Azerbaijanian exports to the EU reached about US$12.3 billion in 2021, with imports of about US$1.6 billion. However, it is the EU transit trade with China that is of the greater interest and volume.

Kazakhstan to China

The Caspian Sea route from Azerbaijan’s Baku Port to Kazakhstan’s’ Aqtau Port is some 296 nautical miles and takes a little over 24 hours to accomplish. However, the Caspian is a temperamental sea and storms can arise causing delays. Furthermore, the vessels used are relatively old in terms of design and in need of upgrades and potentially re-engineering – the Caspian Sea is shallow – it is the second lowest place on earth at 27 metres below normal sea level, rendering deep water vessels impractical. Shipbuilding techniques need to be modified while the existing and available Caspian Sea fleet also needs improving and enlarging. But herein lies a problem – the largest available shipyards able to repair and build Caspian Sea vessels are at the Lotos Shipbuilding Plant in Russia. In their infinitive wisdom in assisting EU trade and supply chain developments, the United States Treasury has placed the Lotos shipyard under sanctions. That means that either certain sanctions need to be re-evaluated, or Caspian shipyards need to be developed elsewhere. Baku has just the other facility, however it appears that developing a Caspian Sea shipbuilding industry may well be on the agenda for Kazakhstan.

The Caspian Sea routes are collectively known as the Trans-Caspian International Transport Route, or TTITR, and came into existence in 2017, mainly by means of an agreement among Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Kazakhstan, in coordination with China, Turkey, and Ukraine. The route notably circumvents Russia. Considered an afterthought at the time, its significance has grown immensely since the outbreak of Russian-Ukrainian hostilities and the imposition of sanctions on Russia.

The route, also known as the Middle Corridor, has never previously fulfilled its potential, as the direct rail service from China, Kazakhstan onto Russia, Belarus, and Europe was considered faster and less expensive. Kazakh Industry and Infrastructure Development Minister Kairbek Uskenbayev said in 2020 that the workload at Aqtau and Kazakhstan’s nearby Kuryk Port were only at 23% of capacity.

That is now changing. Traffic along the TTITR has grown steadily since 2017, when around 300 containers were sent along the corridor. In the first half of 2021 alone, that had increased to more than 7,000. Chinese exporters see the TTITR as a more profitable and faster transportation option than going across oceans and envisaged it as an alternative route to the rail freight. Now it has become a primary source of China-EU access.

There have been immediate spin-off benefits for Kazakhstan. It is a major grain producer and since the Ukraine conflict in March has been the transportation of goods across the Caspian from sales of grain to Turkey. A sharp surge in global grain prices since the Ukraine war began – prices have hit record highs of US$430 per ton – means those exports have grown only more valuable.

While capacity building at Kazakhstan’s Aqtau and Kuryk Ports is on-going, and the future of the Caspian maritime services industry still to be settled, the basic infrastructure from Kazakhstan to China already exists as part of the Kazakh rail route that serviced the original China-Kazakhstan-Russia rail freight routes. These were fully digitized, meaning that Blockchain cargo is already operational and there is not a great deal of infrastructure work required – the routes already exist. That is good news for both Kazakhstan’s inland Khorgos Port, the busiest dry port in the world, and China’s similarly named Horgos Port in its Western Xinjiang Province, handling import and export functions either side of the Kazakh-China border.

However, Kazakhstan also has potential for EU sourcing and bilateral trade. The two signed an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement in 2020, which has resulted in significant elimination of tariffs and duties. In 2021, Kazakhstan exported US$18.5 billion of goods to the EU, mainly in the energy and mining sectors. EU exports amounted to US$5.8 billion, mainly machinery and other manufactured goods. A small but growing services industry between the two is also gaining traction and is worth about US$2.5 billion. It should be noted that Almaty remains the commercial capital and is responsible for over 30% of Kazakhstan’s entire retail trade.

Additional EU-Central Asian Access

EU trade spin offs from the TTITR across Kazakhstan heading East include rail connectivity to markets in Turkmenistan, Kyrgyzstan, and Uzbekistan. A future possibility may be Afghanistan. We can examine each of these as follows

Turkmenistan

Turkmenistan has its own Caspian Sea Port at Turkmenbashi, meaning that EU access will usually be via Turkmenbashi direct rather than via Kazakhstan. However there is Kazakh-Turkmen rail connectivity which could be used to service the Turkmen city of Garabogaz, an important source of urea and salt. Turkmenistan is also building road, rail and manufacturing infrastructure leading to Herat, Afghanistan’s largest commercial city. It is likely to be an important route in the future reconstruction of Afghanistan. I will cover the EU-Turkmenistan access and trade developments in the next article in this series. (Free subscription here)

Kyrgyzstan

The European Union and Kyrgyzstan have an Enhanced Trade & Cooperation Agreement that was signed off in 2019, as well as Kyrgyzstan being able to access the EU’s GSP+ trade scheme. This allows Kyrgyzstan to export a range of 6,200 products to the European Union without any tariffs or duties. Current bilateral trade volumes are running at about US$600 million. Kyrgyzstan is connected to Kazakhstan by road and rail, with rail freight connections running through to the capital city and main commercial centre of Bishkek.

Uzbekistan

Landlocked Uzbekistan is a major attraction for the EU as its progressive policies and liberalization are making it attractive for regional investors. Uzbekistan signed off an Enhanced Partnership and Cooperation Agreement with both the EU and UK in 2021, removing tariffs and duty barriers on over 6,200 products. That is expected to significantly boost trade, with bilateral volumes reaching slightly under US$3 billion in 2021. 2022 volumes should be higher as markets react. Uzbekistan shares a 2,300km border with Kazakhstan and has significant road, rail, and air freight connectivity with its neighbor. Tashkent, the Uzbeki capital, is just 13km from the Kazakh border.

CIS / Eurasian Economic Union Influences

EU exporters to the region should consider the benefits of adopting a manufacturing strategy to service the wider Central Asian markets and mix EU and regionally sourced components into finished products. The Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) is a Free Trade Bloc that includes Kazakhstan in addition to Armenia, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Russia. It also has free trade agreements with Serbia, Iran, and Vietnam, and is negotiating others with Bosnia, Egypt, India, and several other ASEAN nations. These are likely to have significant regional trade impacts when agreed.

The Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS) comprises, in addition to the EAEU nations, Azerbaijan, Moldova, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. This is not a Free Trade bloc but individual members do have Free Trade Agreements with one another. Establishing a manufacturing / processing presence in the Kazakhstan-Central Asian region would allow access to these additional markets.

Summary

Although infrastructure development work and capacity building needs to be undertaken between the EU, Caucasus and to some extent Caspian Sea services and Kazakhstan’s Aqtau and Kuryk Ports, the rest of the route through to markets in China is already well prepared and highly capable of mass rail freight transit, having been put in place to accommodate the original overland routes via Russia.

Meanwhile, with recent EU trade agreements with numerous Central Asian nations being agreed in the past two years, trade potential has been incentivized. Traditionally unusual, but now verifiable trade and investment opportunities exist for EU traders, exporters, and manufacturers along these routes.

Related Reading

About Us

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists British and Foreign Investment into Asia and has 28 offices throughout China, India, the ASEAN nations and Russia. For strategic and business intelligence concerning China’s Belt & Road Initiative please email silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com