Will The BRICS Confront The West At The G20?

Global trade structural changes appear likely at September’s G20 summit in New Delhi

The annual G20 summit is nearly upon us as New Delhi is poised to host the event from September 8th. Interestingly, the summit for the first time provides us with a glimpse of how the emerging BRICS bloc will – or will not – face off against the West.

The BRICS comprises Brazil, Russia, India, China, and South Africa, with upcoming members Argentina and Saudi Arabia also taking part in the G20. Added to this mix are Indonesia and Turkiye, both of whom have stated an intent to join.

They are poised to rub shoulders with the collective West – the United States, Canada, Australia, UK, European Union, Japan, and South Korea. Mexico has also appeared to throw its hat in the ring with this group, with the Mexican President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador stating last week that the country would not be seeking BRICS membership.

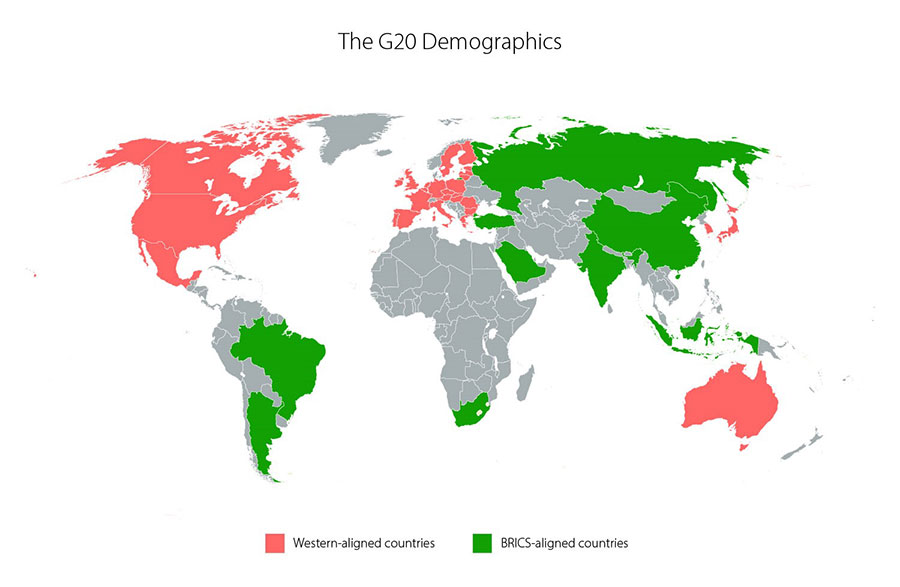

As our map shows, these two groups are somewhat disparate.

Hosts India are keen to play down any potential for competitiveness, both being pragmatic, and taking a strategic position that encompasses both camps. In trade, India views the BRICS as a emerging partner that can give it a globally visible and influential role, a position it is unlikely to be able to achieve within the remaining post-colonial and highly competitive G7. Yet on the other hand, India is a member of the Quad security alliance, in part to keep an eye on its strongest regional competitor and in some quarters, threat – China. New Delhi then will be looking for cooperation within the G20, and to present itself as a bridge between the Old World and the New World.

The BRICS themselves have also been reluctant to position themselves as taking sides, with several ministers present at their recent summit in South Africa denying that the BRICS was set up to compete with the West. Li Kexin, Director-General of Department of International Economic Affairs of the Foreign Ministry of China, stated quite categorically at the event that “The BRICS are not anti-West”.

However, that doesn’t necessarily mean that the West itself feels that way. The past week’s overly negative media coverage of the BRICS expansion (examples here, here and here among many others) appear to indicate that the West itself does feel pressurized by the emergence of the BRICS bloc.

An Immovable Object Meeting an Irresistible Force?

If so, we appear to have an intensely capitalist, highly organised structure, with a win-at-all costs mindset, meeting a more zen-like structure based upon a looser, more organic collective.

Clearly, the upcoming G20 summit will be somewhat different in that despite India’s rhetoric, a division between the West and BRICS has now emerged – the fundamental point about the BRICS enlargement last week. Does this matter?

That depends upon one’s perspective. On one hand, the West’s public opinion appears to have stated that the BRICS are a diverse grouping with limited or no compatibility and is therefore not much of an issue. Many have suggested it will probably fail due to internal divisions such as China v. India, Saudi Arabia v Iran, and Russia v the entire West. A future BRICS collapse into irrelevance is predicted by many who view the bloc as unsustainable.

Yet there is a glue that binds the BRICS together. The individual members are all part of their respective Free Trade Areas, and in most cases the dominant trade partner. Taken from that position, the BRICS has influence over 84 countries and a collective GDP (PPP) double that of the West.

Here, the current, highly aggressive Western approach to trade – where sanctions, and tariff barriers, not bilateral agreements currently dictate what gets sold where, meets a bloc apparently committed to free trade. These are Polar opposites.

The Winds of Change

This in turn calls into question the viability of the G20 as a collective bloc. In fact, the BRICS have already recognised this. China, India, and Russia, individually and within the BRICS have expressly stated in their respective foreign policy development statements that Africa be given a voice on the G20. This is an opinion that will be expressly put forward in the G20 New Delhi, where no African nation currently has a voice in these multilateral discussions.

There is precedence – the European Union is part of the ‘G20’ – meaning that the African Union – the collective voice of all 55 African countries – could also be invited as a permanent guest or even full member. Collectively, the African Union has a GDP (PPP) of US$1.515 trillion, making it the eleventh largest economy in the world. Yet no-one from Africa has any input in the G20.

The same is also true of Central Asia. The Central Asian nations of Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Mongolia, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan possess a combined GDP (PPP) of US$525 billion. These are small numbers by the standards of the G20, but the point is made – this vast region has no representation.

These points – and especially Africa’s case for inclusion – can be expected to be put forward in New Delhi. The interesting issue is how the West will respond. Will it view the inclusion of Africa as diminishing its influence? Or be accepting that collectively, the continent should have a voice in the global community?

Sanctions and Tariffs vs. Free Trade and the WTO

In terms of trade, the G20 – and especially the United States and European Union – will also come up against Russia, whose Foreign Minister Sergey Lavrov will be attending in person. On the sidelines, but as sanctions impacted third party countries, will be China, India, Saudi Arabia and Turkiye, all of whose trade and supply chains have been obstructed by Western sanctions. With the West in full-on sanctions and tariffs mode as a way to impose will, the BRICS bloc may provide some push-back. This is because again, China, Russia, and the BRICS themselves have made it very clear that they view the WTO as having been sidelined by the West in terms of rules of engagement and wish to see its reinstatement as an arbitrary body as opposed to singular action.

The 2023 BRICS Declaration, released just last week, called for an “open, transparent, fair, predictable, inclusive, equitable, non-discriminatory and rules-based multilateral trading system with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) at its core.”

What happens in New Delhi depends partially on how far the BRICS members are prepared to push the United States and European Union into recognising their WTO commitments and to cease the mindset of the arbitrary imposition of tariffs and sanctions while bypassing any WTO consultations.

This is quite apart from fireworks that may be expected between the United States, and European Union, and especially when it comes to Russia. The US President Joe Biden has stated that “Russia should be expelled from the G20” while at other recent G20 meetings, US, Canadian and British officials walked out as Russian delegates prepared to speak.

Such behaviour would embarrass India, as gracious hosts. It would also tend to highlight that the West feels insecure not only in its relations with Russia, but also on the larger basis in terms of criticism of their bypassing the WTO and rebuffing any expansion to include Africa in G20 participation.

Development vs. Retrenchment

Here, the G20 allows us an examination, in terms of progress or otherwise of the G20 as part of the global trade and development mechanism. India and the BRICS appear to want to keep it on track. How the West reacts to these proposals will determine whether the G20 format continues to have any real development value, or descends into an argy-bargy of bickering trade disputes dressed up in diplomatic suits.

The BRICS already has an alternative – the expanded BRICS and its further continuation. The West though may become trapped in the G7. What happens at the G20 in New Delhi seems certain, one way or another, to usher in a new era of global trade participation.

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. He may be reached at asia@dezshira.com or connected with via Linked In.

Related Reading