Azerbaijani Geopolitics Sees The INSTC Reconnect With Armenia

Azerbaijan being sidelined as regional over-confidence and ill-thought out partnerships see Baku overplay its hand

Azerbaijan, fresh from defeating Armenia in last year’s Nagorno-Karabakh War is now losing the territorial impetus it had hoped would open new trade and transportation corridors.

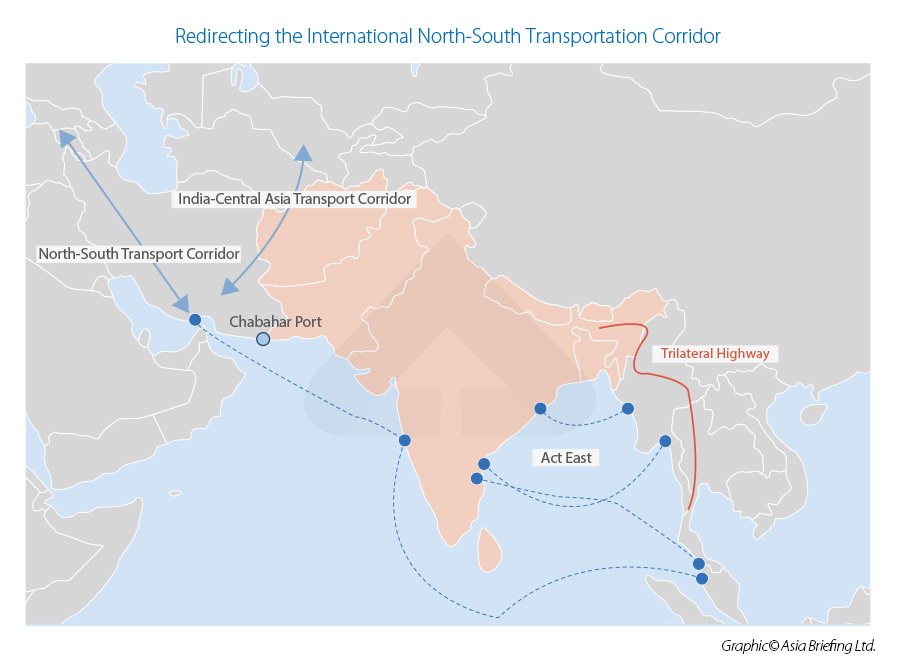

Instead, problems because of that dispute have manifested themselves with a more militant type of attitude creeping into both the Azeri military and Government, so much so that nearby Iran and the massive market potential of India and Central Asia are redirecting trade routes away from the Azerbaijani axis. This means that routes as part of the International North-South Transportation Corridor (INSTC) are being redrawn. Although the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway functions as a corridor from the Caspian to the Mediterranean traversing Azerbaijan, Georgia, and Turkey; that route concentrates purely East-West and involves China, Central Asia, and Russia before reaching Turkey and into Europe. The hugely invested regional powers of Iran and India, key partners of the INSTC are instead looking to bypass Azerbaijan entirely.

The original INSTC route runs through India, Iran, Azerbaijan, and Russia. Azerbaijan made massive investments to improve their local infrastructure to accommodate the necessities of the INSTC, completing roads, railways, bridges, and tunnels. However, despite their economic commitment to be a key player in the INSTC, developments within Azerbaijan’s ideology, in part fueled by military victories against Armenia and the recent defeat of Western powers in Afghanistan has led to a cooling of relations with Iran and India and the United States.

In terms of India, Azerbaijan has become increasingly vocal in condemning India’s policies towards Kashmir in support of Pakistan. A triumvirate formed between the foreign Ministers of Azerbaijan, Turkey and Pakistan has seen each support the Nagorno-Karabakh dispute in Azerbaijan’s favor, and seen them conduct joint military exercises, including close to the Iranian border. Azerbaijan, emboldened by taking much of the Nagorno-Karabakh region has made it known that it regards Iran’s north-west territory, which also possesses a large Azeri population, as rightly belonging to Baku’s control. That has not gone down well in Tehran.

The Azerbaijan-Turkey-Pakistan alignment has further wider implications with each committed to supporting each other’s territorial claims in Armenia, Iran, Cyprus, and Kashmir, potentially unsettling a region from the European Union to the Himalayas.

These developments have led to Alireza Peymanpak, the chairman of Iran’s Trade Promotion Organization, saying on Monday that “Two alternative Iran-Eurasia transit routes will replace Azerbaijan’s route. The first of these opens in November via Armenia after Nagorno-Karabakh war repair work has been completed, and the second via the Caspian and Black seas.”

India and Iran announced that the INTSC from next month will begin running through Armenia instead of Azerbaijan to reach Russia. This is feasible, and more economically attractive. The highways from the Iranian border to Yerevan are already fully funded by ADB and, while behind schedule, will provide a high-speed all-weather highway from Iran to Georgia through Armenia. Past plans for a new US$2 billion railway line, from where Indian and Iranian freight can either go by ship to Novorossiysk in Russia, Odessa in the Ukraine, two EU ports at Varna in Bulgaria, or Constanta in Romania, or by road to Vladikavkaz in Russia’s north Caucasus.

This route between Iran, the Caucasus and Russia is 30% cheaper and 40% shorter than the current route and serves as a geopolitical tool to further isolate Azerbaijan as its relationship with Iran and India deteriorates.

The Indian reaction to the Azerbaijan-Turkey-Pakistan nexus has been swift, with Baku perhaps caught by surprise. India is huge emerging economy, that nearby states such as Saudi Arabia now want to court. Riyadh has significantly cut its funding to radical Islamist organizations in Pakistan and Afghanistan to find a new regional balance, including with India. It recently applied to join the Shanghai Cooperation Organization with a specific remit to secure Afghanistan in the wake of the US departure and is working with China, Russia, Iran, and India to do so. Traditional jihadist financiers across the Arab States have stopped money flows as they prioritize developing their economies and modernizing regional infrastructure.

Pakistan is increasingly seen as more of nuisance, despite its Muslim background, partially because it exports jihadists, an image that Arab states like Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates are trying to break away from. Arabic faces are instead turned towards India just when Azerbaijan is turning towards Islamabad. Saudi trade with India has skyrocketed as a result – bilateral trade reached US$33.09 billion in 2019-2020, whilst between Pakistan and Saudi Arabia it was only US$1.7 billion in 2019.

Azerbaijan meanwhile has swung from a position of regional euphoria to one of disarray. Instead of being a conduit for increased trade because of winning the Nagoro-Karabakh conflict, it instead finds itself increasingly reliant upon Turkey and Pakistan and possesses only cordial ties with Georgia and Russia. Transit routes between Turkey, Azerbaijani exclave Nakhchivan and Azerbaijan proper have yet to be realised or even agreed upon in detail beyond brief reference in last year’s ceasefire agreement.

Turkey is also stretched, the Lira is at a record low against the US dollar and has limited capacity to deal with another military front in the Caucasus, especially as it is seemingly preparing for a new operation against the Kurdish People’s Protection Units (YPG) in northern Syria. This effectively means that if Azerbaijan was to provoke another war in the region, it is unlikely that Turkey can offer the same support it did against the Armenians – and especially if Iran is involved. Neither is Pakistan in anyone’s good books – the US has effectively downgraded its relations and is keen to develop a US-India policy as opposed to a US-India & Pakistan policy, leaving these three new friends in something of a bind.

This is good news for Armenia however, which had become something of a bit-player in the overall Belt and Road Initiative as faster routes were developed via Baku. Now, the pendulum has swung back again, and the INSTC, although not a BRI project, is certainly a key component part as it links with other BRI corridors elsewhere. There are other trade dynamics that support an Armenian favored route. The country, along with Russia, Belarus, Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan is a member of the Eurasian Economic Union, a free trade bloc that is currently negotiating tariff reductions and free trade agreements with India, Iran and China. These are close to being finalised meaning investment in cross-border trade in the Iranian-Armenian area should be seriously considered by both domestic and other foreign investors.

Related Reading

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com