Impact Scenarios Should The EU Impose Secondary Sanctions On Central Asian Economies For Providing Parallel Exports To Russia

Analysts deem EU sanctions against Central Asia as likely to miss their targets and being fraught with significant risks

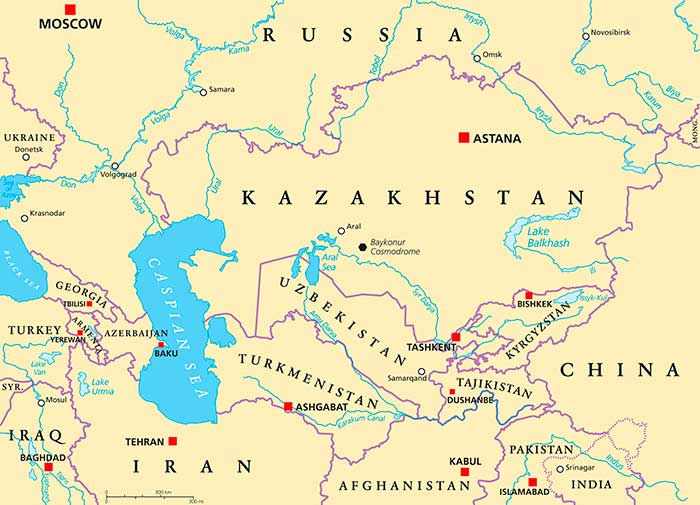

The European Commission has announced the upcoming 11th package of anti-Russian sanctions, which will not now be specifically against Russia, but against third countries supplying sanctioned goods to the Russian Federation. Central Asian states have fallen under suspicion because they boosted their exports to Russia in 2022. In March, the EU Special Representative made an ‘inspection’ visit to Kyrgyzstan, and similar meetings will be held in Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan at the end of this month (April 2023).

The details of secondary sanctions and possible timing of their introduction have not yet been officially announced. In general, the position of European countries on this issue became obvious from recent publications in the Western press. The UK’s Daily Telegraph published EU internal documents, which stated that “(The EU) should give a strong signal to persons and entities in third states. The provision of material support to Russia’s military and defense industrial base will have severe consequences regarding their access to the EU markets.”

This applies to products that may have dual use. For example, microchips in washing machines, cameras, and even air conditioning equipment can, according to some experts, can be used to repair military equipment. According to the Telegraph, trade between Russia and Central Asian states saw a significant uptake between 60 and 80 per cent last year – much of this being suspected of having ‘dual use’.

Analyzing Trade Flows

The EU’s overall figures are approximate without detailed analysis. However, the Central Asian Bureau for Analytical Reporting (CABAR) did conduct analysis of the Central Asian countries national databases of foreign trade for 2021-2022 and drew the following conclusions:

The trade flow between Kazakhstan and Russia in 2022 increased by 6.1%, with a 25% rise in Kazakh exports; Kyrgyzstan boosted mutual trade with Russia by 40.3% including a rise in exports from Kyrgyzstan of 2.4 times; bilateral trade between Uzbekistan and Russia showed 23.4% growth, with exports to Russia rising by 49%.

The statistical committees of Tajikistan and Turkmenistan do not provide open data on foreign trade, but their statistics can be tracked down by figures voiced during official visits of Russia’s representatives to these countries. According to Mikhail Mishustin, the Russian Prime Minister, the 2022 trade turnover between Russia and Tajikistan increased by 18%, reaching a record US$1.5 billion. Turkmenistan and Russia boosted mutual deliveries by 32.7% (data available for 8M 2022 only). This statistical data does show an overall growth, based on many factors, including a buoyant trade increase with Russia in any case; a Covid rebound – but also the substitution of European suppliers in the Russian market.

It is important to note that not all Central Asian countries can provide detailed statistical data that can absolutely prove the export of goods purchased in Europe, United States, not in China, from the regional countries to Russia.

Testing the Hypothesis

We have tested this hypothesis based on data available for Kazakhstan. It turned out that the share of imports to Kazakhstan from the EU and UK and the United States is relatively low in different groups of commodities: phones – 7%, computers 16%, refrigerators – 24%, etc.

The main portion of these high-value added products are actually imported from other countries. Smart phones for example are manufactured in China and India, washing machines in Vietnam, and so on. This means it is difficult to check which commodities were exported to Russia – European or Chinese (which is not prohibited by sanctions) without disclosure of internal commercial information.

Accumulating Evidence

This evidence base is very important when countries are to be charged with sanctions evasion, especially when taking into account the official position that largest countries of Central Asia meet the requirements of prohibition of re-export to Russia.

Therefore, before making significant statements or imposing sanctions, EU representatives have planned to hold a range of meetings in Central Asia. One of these already took place on March 28 in Bishkek. The EU’s Special Envoy, David O’Sullivan, visited Kyrgyzstan, and outlined his goals as follows: “The purpose of my visits is to open dialogue with these countries in order to determine if sanctions are being evaded. If they are, this should be stopped.” The EU is preparing to send a team to Kyrgyzstan in the Autumn 2023 to do this job.

Sovereignty Issues & Existing Agreements

However, according to Aman Saliev, a director of the Institute of Strategic Analysis and Forecasting (Kyrgyzstan), any monitoring should not in any way violate the sovereignty of the independent state (in this case, Kyrgyzstan). Bishkek implements an open trade policy, to UN standards, which includes the disclosure of foreign trade data.

In fact, Saliev points out, the trend towards boosting the trade turnover between Kyrgyzstan and the EU has been in place for many years and is part of the EU Central Asia Strategy which was updated as recently as 2019. This focuses on resilience (covering areas such as human rights, border security and the environment), prosperity (with a strong emphasis on connectivity) and regional cooperation and trade. This Strategy long predates the Ukraine conflict.

According to CABAR, “The visit of the special envoy of the European Union to Bishkek and his statements that Kyrgyzstan must provide cooperation in the implementation of sanctions, can partly be considered as interference in Kyrgyzstan’s domestic affairs. Kyrgyzstan has taken a neutral position since the beginning of the conflict in Ukraine and sticks to this position. If EU representatives claim there are parallel imports to Russia through Kyrgyzstan, why don’t EU authorities take restrictive measures to sellers of those commodities directly in the European Union?”

This would appear a relatively simple thing to accomplish. All the EU would need to do is to restrict exports of sanctioned items to Central Asia to the volumes they were at the end of 2021, two months before the Ukraine conflict began. A small volume allowance could be made to factor in natural demand (all the Central Asian economies are growing). Instead of sanctioning third parties, the EU could prevent the export of excessive amounts of EU products to Central Asia (or anywhere else) and keep the subject within its own borders.

In fact, the EU is inconsistent in its approach as it still maintains active trade relations with Russia in many items and according to its own published statistical data, EU imports from Russia reached a record high in 2022 despite the imposition of sanctions.

According to Kyrgyzstan’s National Statistical Committee, in 2022 the share of Russia as part of its total trade turnover with other countries was 27.4%. Last year, Kyrgyzstan and Russia exchanged goods and services to just over US$3.2 billion, an increase of 40.4%. However, Kyrgyzstan’s trade with Europe in 2022 declined at US$ 666 million, a drop of 1.1%. Comparisons of trade turnover amounts should be taken into account.

Potential Impact On Central Asia Of EU Secondary Sanctions

We asked several analysts if imposing secondary sanctions against Central Asian states at the national level is a potential scenario.

Serik Yernar, director of the Centre for Trade Policy Development at Kazakhstan’s Institute for Economic Studies stated that “If the EU proves the cases of re-export, these measures will be directed against violators, not the country. Kazakhstan does many things to minimize the circumvention of sanction restrictions via the territory of Kazakhstan.”

This means that the EU would impose sanctions on specific Kazakhstan businesses and individuals.

However, Yernar also pointed out that Kazakhstan, whose main exports are fuel and mineral products, is a major supplier to the EU, being the main importer of these products, as well as Russia, whose territory is used for the transit of oil to the EU. Kyrgyzstan keeps neutrality and follows preliminary agreements with each of the conflicted parties.

Nikita Mendkovich, Chair of the Eurasian Economic Club, said that “Imposing large-scale secondary sanctions at the national level is highly unlikely. It will lead to the absolute split of the world and loss of American influence on many countries. Sanctions are being imposed at the level of particular companies, including in Central Asia, but do not affect the general situation.”

She added that “Central Asian countries continue to participate on a large scale in the practice of parallel imports. In Kazakhstan, which regularly claims that it will not help evading sanctions as suppliers of sanctioned goods, these businesses are owned by political elites.”

Aman Saliev reiterated that at the initial stage, sanctions imposed by the EU will only have a short-term impact on Central Asian economies, as countries will develop measures to substitute against such prohibitions, saying that it is more likely that if EU sanctions are imposed, then Central Asia would merely re-orientate towards closest partners – China, Russia, Iran and Türkiye.

He said that “Based on available information, it is unclear what the proposed EU sanctions will be. We can predict probable restrictions on the export of goods sanctioned in Russia to Central Asia, additional restrictions in Capital flows, Banking services, or partial to full closure of the European market for the region. In Kyrgyzstan, the European Union can restrict or stop funding of a range of humanitarian projects.”

Central Asia Fights Back

Medkovich stated that “The hypothetical introduction of sanctions against Central Asia or their leaderships will cause not only a final breach with the United States, but also the nationalization of Western assets in Central Asia. The United States and EU gained control over many oil and ore deposits back in the 1990s in Kazakhstan. Secondary sanctions will cause nationalization of these facilities, and the local society will support this measure. Sanctions would result in visa bans for key US and EU politicians and the wider population, causing counter measures against the EU and accelerate the breach with the West.”

But not everyone agrees. The scenario with trade restrictions and visa ban is impossible, said Yernar Serik. “This way makes no sense for any party. The Central Asian countries supply commodities such as oil, farm produce, and other raw materials to European markets, which now lack them due to their Russia sanctions and disruption of trade and supply chains. With no viable Russian alternatives, there is a transit flow of goods between the European Union and China via Kazakhstan. If the EU introduces sanctions, such a break in relations can lead to a significant reduction of trade and economic presence of the European Union in Central Asia as well as the loss of other tools of influence. Having cut off Russia, they would be most unwise to do the same to Central Asia.”

The last word goes to Saliev: “Perhaps, Europe understands the possibility of these outcomes and tries to find a compromise first. If the European Union, United States and other countries continue to put pressure on Kyrgyzstan and its Central Asian neighbours, Kyrgyzstan and the neighbouring republics would take it as interference in domestic affairs and the act of foreign political dictate, which would cause an enormous harm to prospective cooperation between the European Union and Central Asia.”

Source: Irina Osipova for CABAR

Related Reading