Winners & Losers in the EU’s Digital Connectivity with China & the OBORSphere

The digital economy, also known as the internet economy, is based on digital computing technologies, comprising new business models such as e-commerce, cloud computing, and payment services. Technology is functioning as a new engine for the development of new revenue streams and enabler of new business models. With China possessing one billion consumers able to access the digital economy, and the State Government putting into plans to deliver to 95 percent of China within 24 hours by 2020, the opportunities for getting produce both into and out of China and the OBOR region as a whole are immense. The digital revolution is impacting on the essential deliverables of the OBOR routes – getting product delivered, on time, safely, and securely. This includes not just e-commerce, but also e-customs and e-government. Supporting services will all be managed by e-platforms.

5G networks are expected to bring about a veritable revolution in business processes owing to the brand new technological opportunities that come along with them. The industrial Internet of Things, smart cities, self-driving cars, telemedicine and other promising development areas will get a fresh start following the 5G standardisation, which will be trialed in countries such as Russia as early as next summer and rolled out as a service by 2020 – just three years from now.

Both China and Russia are making giant steps to transform their economies and gear up for their entire markets being dominated by the digital evolution. Both nations also recognize the urgent need to synchronize systems, develop compatible standards, and allow use of such technologies to speed up trans-shipment, logistics, warehousing, and end delivery systems to consumers.

It is pertinent to examine what this means in terms of potential for Europe to integrate and which countries are likely to be better placed to synchronize systems, and therefore cross border trade and commerce, with China, Russia and the entire One Belt, One Road initiative, or OBORSphere.

The comparison is important as although many EU politicians fear the rise of China trade, assuming that cheap Chinese goods would flood domestic markets, in fact the Chinese are rather more pragmatic and structured in their export approach than many would give credit for. There is no sense for China to ruin small localized economies in Europe just to access wealthy markets. Instead, the continual provision of inexpensive, yet targeted products too expensive to be manufactured in Europe is rather more the key, while China’s economy is also expected to reach 550 million middle class consumers and 1 billion e-consumers by 2020. It is worth noting that China, with its 20% of the global population, only possesses 5% of the worlds arable land. The country is energy and agriculturally poor and needs to secure and import these products. The EU is in a unique position to supply this demand.

Innovation however, and especially in the first phase of securing China’s needs, is required, and to this end China, and Russia have both embarked and will continue to embark on projects that combine technologies – including joint ventures with European businesses. Examples are Siemens involvement in the Moscow-Kazan high speed rail a project that may later extend all the way to Beijing, and the Chinese funded development of electric vehicles in Bulgaria and Romania – following which China announced all Volvo cars would be electric by 2019, the first major manufacturer to make such a statement. Clearly, China is looking to Europe to innovate and create and develop new technologies to support global trade as the century progresses. Sitting on the bedrock on basic Chinese needs, this is a good place to begin examining the opportunities that this can bring EU nations. However, in order to do so, connectivity needs to be in place. China, for its part, has announced it will be investing USD411 billion between 2020 and 2030 on upgrading its entire telecommunications system to 5G. How does Russia and the rest of Europe stack up in matching China’s development and technology standards? Which countries are well positioned and aware and which need to get their act together? Understanding these issues is key to understanding which cross border points in Europe are likely to be more successful than others.

We can examine the strengths and weaknesses of the partners involved as follows:

Digital China

China has been making great strides in developing its digital economy, which according to a White Paper issued by the Chinese Academy of Information and Communications Technology (CAICT) and Ministry of Industry and Information Technology (MIIT), expanded at 18.9% in 2016, much faster than that of China’s overall economy, which grew 6.7 percent during the same period. In total, China’s digital economy accounted for 30.3 percent of China’s total gross domestic product (GDP) over the year, said the white paper. Taking its spillover effect into account, China’s digital economy contributed 69.9 percent to its GDP in 2016.

KPMG has issued a report on this stating that the growth of China’s digital economy and the emergence of many new business models as a result has triggered a wave of new and complex issues for companies operating in practically all sectors of the Chinese economy. However, it is not all plain sailing.

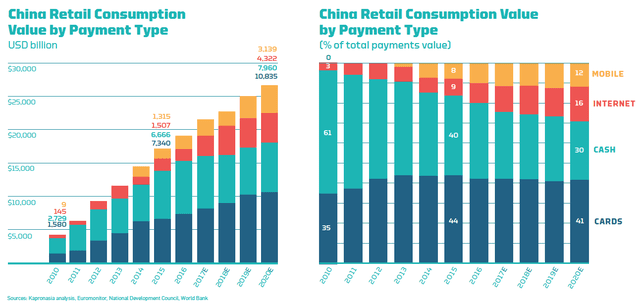

China has some difficulties with telecommunications due to mountainous terrain and a still-developing communications satellite need. Nonetheless, China’s enormous projected spend will take care of the terrain and satellite gap. As at today, about 731 million Chinese are online, with 95 per cent of them accessing the internet via their phones. This has spurred the development of arguably the most dynamic mobile ecosystem in the world. China’s digital payments market as a result has exploded to about 50 times the size of that in the US. It may take time for China to roll out 5G across the entire country, however the primary cities, manufacturing and distribution hubs and crucially transportation border areas are all being prioritized. China is a leading player in digital connectivity and has the architecture and the finance to further develop this. This includes not just State planning but also China’s private sector, which also also taken huge steps to get on board. Huawei for example have been investing what is expected to be a total of US$600 million for R&D in 5G technologies since 2013 until 2018. That dwarfs investments being made by EU businesses in the same technological field.

Businesses such as Tencent and Alibaba, with a combined market value of more than U$500 billion, as well as China’s tech companies are also forging ahead with innovation and investment on their own. Tencent, a gaming-to-messaging powerhouse, is using its popular WeChat app as a platform for an array of other services, including digital payments. Similarly, Alibaba, whose core e-commerce platform serves millions of businesses across the world, has diversified into other online markets and financial services. With 120 million Chinese tourists travelling abroad every year, Alipay is fast becoming one of the most global digital payments services. It should be noted by European governments and businesses that the new wave of Chinese tourist visiting their cities will want to be acquiring European clothes, foods and products to take home and integrate into their daily lives in future, and they will be expecting service that can deliver produce from Europe with the minimum of delay and fuss.

Digital Russia

Russia has approved a rolling, three year plan worth USD1.6 billion per annum to upgrade its own digital network. That is equivalent to about a third of China’s total spend per head of population over the next decade, but also accounts for the fact that many of Russia’s citizens live in relatively easier to access cities than China’s and it already possesses superior satellite technologies with craft already operational and in orbit. Moscow expects to be one of the first global cities to be 5G by 2020, a task that will rank it ahead of cities such as London and made somewhat easier due to the upgrade in communications currently taking place to prepare the nation for next years FIFA world cup finals, which is expected to feature a pilot 5G zone. By 2020 Russia plans to roll out 5G networks by 2020 in eight cities.

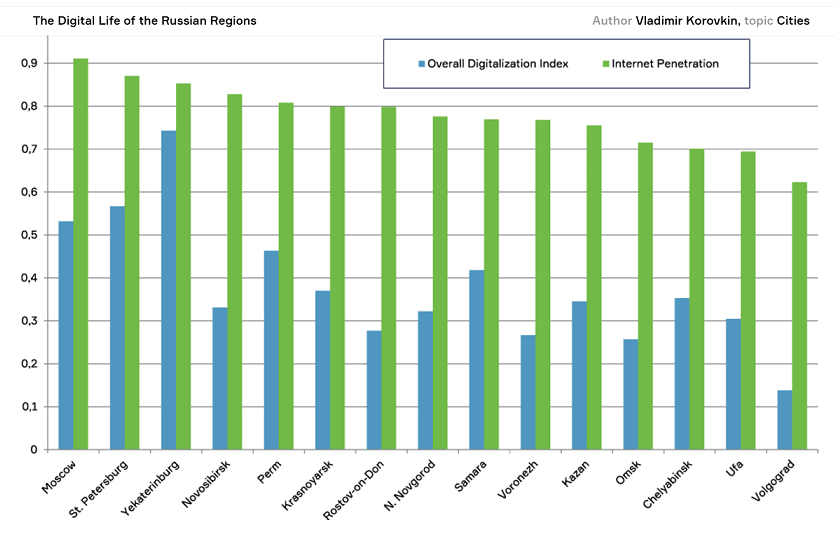

The Skolokovo School of Management recently released a report into Russia’s digital connectivity, entitled the “Russian Regional Digital Life Index“. with the aim of studying the existing levels of digital penetration on everyday life, including transport, finance, retail, education, healthcare, media and public administration, together with the supply and demand for digital services. What was found is that Russia has already reached the second phase of connectivity – the apparatus is in place, now it is starting to yield results. This is a measure of intensity rather than breadth of usage and accordingly puts Russia ahead of China in this regard. Also of interest were the city results – Yekerterinburg ranked higher than Moscow, St.Petersburg and Novosibirsk in overall digitization, a mark of the cities modern and innovative culture. The results are below:

It should also be remembered that despite sanctions, the Russian economy itself is now growing at a faster rate than the EU’s, and there is huge pent up demand. Russia’s middle class consumer base is about 75 million, roughly 50% of its total population and among the highest percentage total among the BRIC nations. It should be remembered that prior to the sanctions, bilateral trade with the EU was worth some €276 billion and had just reached a record high. Russia at the time was the EU’s second largest trade partner, with about 85% of EU exports to Russia being in manufactured goods. The vast majority of that trade has now passed to Asia. The EU sanctions upon Russia are a direct cause of an huge increase in Russia’s trade with China, which has consequently been growing at rates of 30% per annum

In summary, Russia still has a lot of work to do in digital connectivity east of the Urals and across to Vladivostok, but European Russia is well prepared. It can be expected that lines such as the Trans-Siberian and other routes, will however be to 5G standard, even if the surrounding, often remote areas around such routes may not be. No-one is buying much in deepest Siberia, with one of the lowest population densities in the world, a fact that makes Russia’s 5G ambitions easier to deliver and manage. With a mandated budget in place, Russia is set to continue its digital connectivity and take its place at the 21st century e-commerce and trade table with China. With the digital economy largely able to bypass sanctions – import-export tariffs excepted – both Russian and EU businesses will be able to find new methods of doing business with each other, and especially should pressure to permit cryptocurrencies in trade start to take effect. The current sanctions have effectively highlighted the problems in relations between the EU and Russia, but at the same time, have demonstrated a real degree of interdependence between their economies. The imposition of sanctions has instead provided an opportunity to create new cross-border value chains. With Russia a de facto vast border region between China and the EU, having Russia up to speed will prove vital to both Chinese and the EUs prospects of maintaining and developing trade. But there is a down side. Without Russia on board and synchronized between Asia and Europe, the entire global economy is in danger of significant trade risk. EU politicians should take note of this potential bottleneck.

Digital Europe

A benefit that both China and Russia has is that they deploy consistent, sustainable and well organised, disciplined political systems lead by strong leaders who embrace vision and new technologies. The EU in comparison is something of a federal, argumentative menagerie and is becoming increasingly divided, with Greek Euro bailouts, Brexit and Poland now disobeying Brussels over who controls its national courts. There are a variety of Digital Europe development blueprints such as the Digital Agenda for Europe however operating standards among EU members are in disarray, while financial and visionary support appear sporadic and de-centralized. Monies made available for research and integration also pale when compared to the vast sums being allocated by China and Russia. Research grants provided by the EU for example amount to tens of millions of Euros rather than the hundreds of millions and even billions China and Russia are deploying.

The EU is far from being as digitally integrated as either China or Russia are. Beijing is concerned about this, and has already called for stronger Asia-Europe digital connectivity. As a result, it will almost certainly mean that much of the EU’s 5G technology will ultimately be supplied by Huawai and other Chinese businesses. Such partnerships are already occurring; Huawei is working with Ericsson in testing 5G technologies in rural parts of the Netherlands, and is also testing 5G technologies in Malta. To date, just Amsterdam and Turin have announced plans to deploy 5G by 2020, and these are only pilot projects aimed to coincide with another football tournament, the European Championships which take place that year in 13 different cities across the EU. No doubt other cities will showcase 5G trials at that time as well, but this is still two years behind Russia’s trials. Germany is even further behind with plans to roll out only by 2025. Europe is consequently way behind Chinese and Russian connectivity in this regard, with Europe’s largest telecoms providers only able to provide a manifesto that suggests just one city in each EU member nation will have 5G by 2020. In short, this implies that much of the EU is just not ready to engage with either China or the OBORSphere in any meaningful way and will not be up to speed for another seven-ten years. If so, these are wasted opportunities for handling exports to China, although as I shall explain a handful of Northern European nations have seen the potential and are are pulling further ahead from other EU nations in the contest to manage Asian imports and exports.

But where does this leave Europe as a whole? The EU’s Digital Economy & Society programme have launched a series of Country by Country progress charts in which each of the EU members capabilities can be measured.

The findings illustrate that while Northern and Scandinavian Europe scores well, it is Eastern Europe that lags behind. Countries such as Denmark, Sweden, Finland, Holland, Belgium and Estonia all score well and are ahead of the curve. (I recently covered Estonia’s unique position in the article China Eyes Estonia As Smartest & Nearest Port For EU Access). However, when it comes to key border nations that really need to be onboard with 5G and digital technologies, Hungary, Slovakia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Greece, Poland and Romania all fare poorly. Many of these are front line nations when it comes to the EU connecting with the OBORSphere, and they are not up to speed.

Bulgaria, Hungary, Poland and Romania all occupy a special place within the EU, as they are familiar with ex-Soviet mentalities and culture, possessing a large amount of Russian savvy. Some of them, such as Poland, are key entry points into the EU, with many transportation links and the necessary conversions from Russian to EU standards all concentrated in this nation. Greece too, mired in debt, is nonetheless a key access OBOR point via Piraeus. Romania and Bulgaria offer strategic geographical advantages to the EU and onward connections through to Russia, the Caucasus, Turkey and Iran, yet rank last and second last in digital capabilities.

In terms of investments, this means that until the Eastern European bottlenecks can be cleared up – which may require significantly more investment from China – it is the Northern European markets who are currently ahead of the OBORSphere connectivity game with China and Russia. Looking much further ahead, this bodes well for the development of the Northern Sea Passage and the ability for China, Russia and the northern EU countries to stamp their mark on trade flows.

Russia too has spotted this and officials from its border regions with Finland and Estonia have requested the Russian Federal Bank permission to allow trade in Bitcoin to allow more finance and trade to enter the region from the EU. As if often the case, it is the border areas who are often the most innovative and recognize the potential – a fact especially true on the Russian side of the EU.

China and Russia will push on regardless; they understand what is about to happen and the opportunities 5G and developing a digital economy will bring. Europe though is divided into three, the innovative and IT savvy nations of Northern Europe, the slow to adapt economies of Germany, France and Spain, and the laggards of East and Southern Europe. For now, the smart OBOR connectivity money will be heading North. But it is the East that needs special attention and investment, and EU-OBOR transit nations such as Poland in particular need to be well aware of the economic dangers of missing out.

About Us

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Founding Partner and Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. He is based in Europe. The firm provides European businesses and governments with strategic, legal, tax and operational advisory services to SMEs and MNCs investing throughout Asia and has 28 offices across China, India and the ASEAN nations as well as St. Petersburg and Moscow. Please contact the firm at asia@dezshira.com or visit the practice at www.dezshira.com

Related Reading:

Related Reading:

Silk Road and OBOR Business Intelligence

Dezan Shira & Associates´ Silk Road and OBOR investment brochure offers an introduction to the region and an overview of the services provided by the firm. It is Dezan Shira´s mission to guide investors through the Silk Road´s complex regulatory environment and assist with all aspects of establishing, maintaining and growing business operations in the region.

China’s New Economic Silk Road

This unique and currently only available study into the proposed Silk Road Economic Belt examines the institutional, financial and infrastructure projects that are currently underway and in the planning stage across the entire region. Covering over 60 countries, this book explores the regional reforms, potential problems, opportunities and longer term impact that the Silk Road will have upon Asia, Africa, the Middle East, Europe and the United States.

![]() Establishing a Foreign Business in Russia

Establishing a Foreign Business in Russia