The Proposed India-Middle East Corridor Is Set to Reshape Eurasian Connectivity, But Challenges Will Persist

By Emil Avdaliani

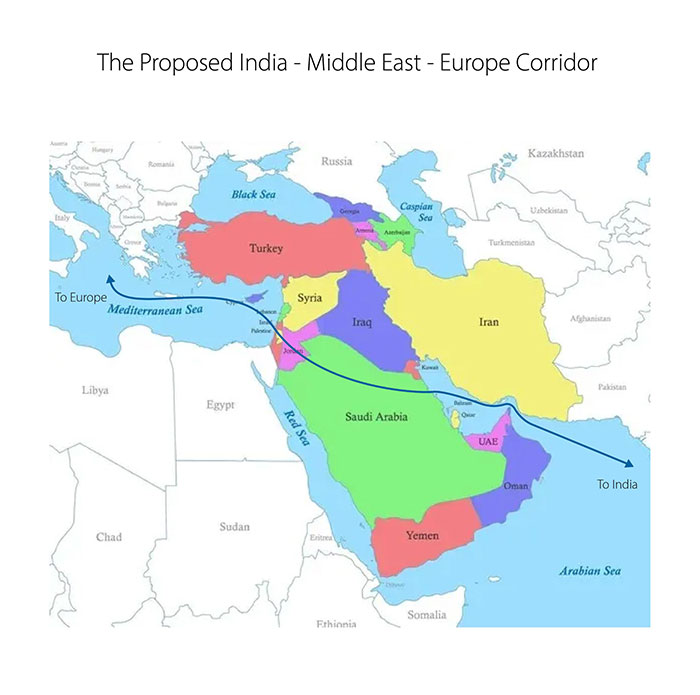

On the sidelines of the Group of Twenty (G20) summit in New Delhi, India, the United States, United Arab Emirates, Saudi Arabia and the European Union agreed to create a transport and economic corridor connecting the South Asia with Gulf monarchies and European countries. Dubbed the “India – Middle East – Europe Corridor” (IMEC), the parties signed a corresponding memorandum of understanding.

According to the White House statement the initiative “will be comprised of two separate corridors, the east corridor connecting India to the Arabian Gulf and the northern corridor connecting the Arabian Gulf to Europe. It will include a railway that, upon completion, will provide a reliable and cost-effective cross-border ship-to-rail transit network to supplement existing maritime and road transport routes – enabling goods and services to transit to, from, and between India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Jordan, Israel, and Europe”.

The project involves the construction of a railway network and the development of relevant port infrastructure from India to the Gulf to the Mediterranean. The participants intend to increase the capacity of routes for transporting export and transit cargo. This is the first cooperation initiative in the field of communications and transport involving India, the UAE, Saudi Arabia, the EU, France, Italy, Germany and the United States. The new corridor is expected to increase efficiency, reduce transportation time and costs, create new jobs and increase throughput via transit routes.

This is not the first major project the US is endorsing with the aim to re-shape global connectivity in ways that will benefit the Washington and major players in the Middle East and South Asia. Another idea was the trans-African Corridor, which will improve the transport links from the province of Katanga in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) and the copper belt in Zambia with the port of Lobito in Angola.

The promotion of the IMEC project fits into Washington’s wider agenda to produce a major diplomatic deal in the Middle East between Saudi Arabia and Israel. More importantly, Washington also considers the IMEC as a part of the Partnership for Global Infrastructure Investment (PGII) – initiative to fund infrastructure projects to counter to China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI).

Yet, this is not how the Middle Eastern countries see the IMEC. First, Saudi Arabia and the UAE consider the initiative not as anti-China project, but rather as a step which would help them economically and infrastructure-wise to be better positioned in the shifting global connectivity, a process which was exacerbated following the Ukraine conflict. Moreover, they also see the IMEC as a way to promote the concept of the multi-polar world. The decision to join the corridor follows Saudi Arabia’s and the UAE’s recent move to embrace BRICS membership – another measure to construct a multipolar order. Overall, with the IMEC project the Gulf countries hope to advance their fledgling muti-vectorial foreign policy. Exclusive dependence on China was never on the table. A similar approach persists in the relations with the United States.

The Gulf countries also pursue their internal agenda. For example, for the Saudi leadership the prospective corridor neatly fits into the agenda the kingdom has been pursuing to re-model the country by creating a highly diversified economy by 2030 and as part of its Saudi Vision 2030 agenda. For the UAE, the participation in the initiative is also about opening up the country and its resources to the wider global audience to attract investment and increase the country’s geopolitical weight.

Similar sentiments prevail in India. New Delhi has long been interested in advancing new trade corridors as a way to counter China’s ambitious projects in Pakistan and the wider Indo-Pacific region. But for New Delhi the launch of the IMEC is much more about its own geo-economic considerations. Indeed, the corridor will provide a long-coveted secure connectivity with the Middle East, the ties which have grown more important to the country as its dependence on Gulf oil increases and Indian diaspora living in the monarchies has also reached significant numbers. India and the UAE have also recently signed a highly productive CEPA trade agreement, the IMEC will assist in boosting this bilateral trade.

The embrace of the IMEC does not mean that India and the Gulf Countries are prioritizing this initiative over the others. In fact, they are actively working with Russia on advancing the International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC) and in case of the Gulf monarchies closer trade and economic ties with China are also pursued. Indeed, trade relations between Russia and India and Russia and the Gulf countries have increased exponentially since early 2022. The first Russia-Saudi Arabia direct freight train arrived in Jeddah via the North-South corridor just last month.

Another basis for the new corridor is India’s push to find new routes to reach the EU market. Bilateral trade has been growing; in the 2022/23 Indian fiscal year the country exported €70 billion to the EU. New Delhi and Brussels are also in talks over reaching a free trade agreement.

Moreover, the EU is also deeply involved in the Gulf Region. The trade between the two regions increased to nearly US$186 billion in 2022. For the EU the push for closer trade ties with India and the Gulf states has become more critical following the outbreak of the conflict in Ukraine when trade routes through Russia stagnated, and the Middle Corridor expanded.

India’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) are also flourishing. For instance, bilateral trade has increased to US$154.73 billion in FY 2021-22 from US$87.4 billion in FY 2021. India’s exports to the GCC witnessed a 58.26% increase to about US$44 billion in FY 2022, against US$27.8 billion in FY 2021. More specifically, bilateral trade between India and the UAE stood at US$84.5 billion in the period of April 2022-March 2023. The two countries have also reached an agreement to settle trade in Rupees and Dirhams, while the GCC and India are also in talks over signing a free trade agreement. Accordingly, the economic ties between the EU, GCC, and India underpin the push to build a new transportation corridor. If free trade agreements are signed between India, the EU, and the GCC, a continuous economic and trade link will be established from South Asia to the Mediterranean.

However, the IMEC will also face its share of challenges. Much of the work still has to be done. For example, it is unclear what the actual demand is along the proposed corridor. Issues related to various regulations, taxations, customs procedures will also need to be addressed and harmonized. The corridor is also multi-modal; consisting of land and sea sections, which are harder to support than either exclusively land or maritime routes. Nor will the route through the Suez Canal be entirely abandoned and it will remain a competitor.

New trade corridors are successful when basic infrastructure is already in place. In the IMEC’s case we see that in Greece (the closest EU ports to the IMEC), railways are poorly developed due both to mountainous geography and a lack of finances. In the Gulf region, Saudi Arabia and the UAE will require the construction of a railway network across deserts – substantially increasing the costs of the project. Neither the United States nor the EU have yet explained how this will be financed.

The geopolitical situation on the ground is also shaky enough to complicate the progress. China, Russia, and Iran will push against infrastructure projects which would undermine their position. Nor is there any certainty that a viable rapprochement between Saudi Arabia and Israel will be reached, while the relations between the US and the Gulf countries are not always free of tensions.

In short, while the IMEC concept appears attractive, much remains to be done to see it through to completion – a result that with previous announcements concerning the US ‘Build Back Better World’ and the EU’s ‘Golden Gateway’ schemes leaves some scepticism as concerns their ability to make the IMEC proposal a working reality.

Emil Avdaliani is a professor at European University and the Director of Middle East Studies at the Georgian think-tank, Geocase.

Related Reading