The China-Russia Axis: What It Is And Why

I was asked by the Italian newspaper L’Indro on Monday questions in relation to the current situation concerning China and Russia and produced the article below. The issues at stake however are very complex and lead into different issues themselves. These are controversial, deep, and difficult subjects and highly emotive to some people. I have tried to simplify the issues at hand, to make them easier to break down and analyze. The Italian version of the article is here. The English version follows:

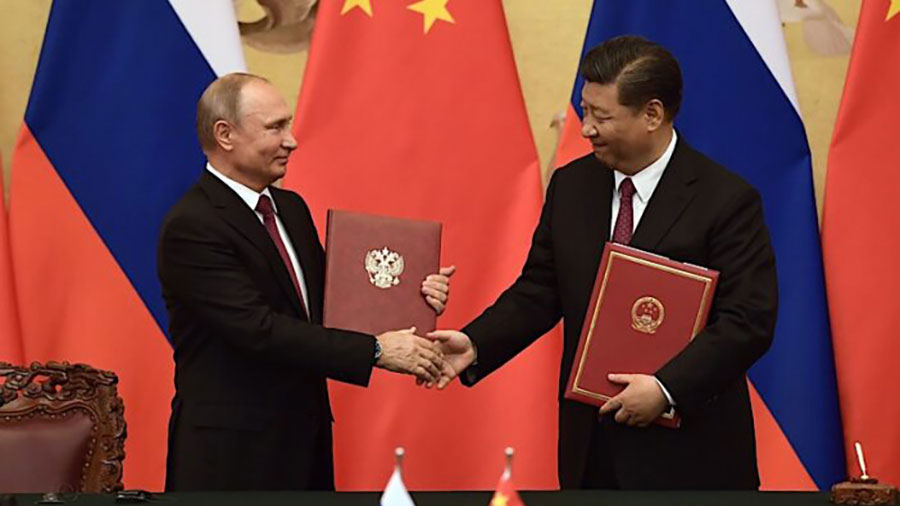

Vladimir Putin’s attendance at the Beijing Winter Olympics Games opening ceremony and the subsequent meeting with Chinese President Xi Jinping have gained a great deal of attention these past few days. This is unusual to some degree – the two have met multiple times in virtual conferences the past two years without much attention being paid – but on this occasion, a global stage, and tensions in both Ukraine and Taiwan, the media spotlight has been intensified. Much of it has been critical. At least one European newspaper called the China-Russia relationship ‘an axis of evil’ while Taiwan called it ‘contemptible’. The United States media have generally condemned the friendship as ‘attempting to overthrow the West’. Even the context of the meeting, at the Winter Olympics has given rise to outrage, with some calling the event ‘The Genocide Games’ in reference to China’s treatment of the Uyghurs. Europe meanwhile remains generally fearful of the prospect of a Russian invasion ‘of Europe’. Hysteria is running at full throttle. Yet what are we to make of these intense views?

Taken as a whole, the entire picture seeks to condemn a China-Russian friendship. But where does the fear and the rhetoric actually spring from? In this case, it is necessary to divide the condemnation into its component parts and deal with them separately. Identifying the root cause of each may shed light on the whole.

Why the references to a ‘Genocide Olympics’?

There are three component parts to this question. Firstly, the term ‘Genocide’. Usually, it has been used to describe human atrocities, such as murder, rape and the eradication of a specific human race or culture. However, the term was modified recently, in 2018 to include a rather broader – and thus greater interpretation of the word’s definition to include two specific terms. These are ‘mental genocide’ which alludes to “intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group” and physical genocide, which relates to ”Killing members of the group, Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group, deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part; imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group; forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.” The term was widened to reflect atrocities that had occurred during conflicts in Rwanda and Bosnia.

Today the term is being leveled at China due to the situation it faces in its Western Xinjiang Province, and specifically the Uyghur population. Beijing is accused of imprisoning up to 1 million Uyghurs, a Turkic ethnic group of Muslims who crucially belong to the Sunni Islamic sect, significant as this is the same doctrine as espoused by the Taliban. Xinjiang Province shares a border with Afghanistan and Northern Pakistan, both fiercely tribal areas who have been subjected to extreme radicalization in the past. While the majority of Xinjiang’s 15 million Uyghurs are peaceful, there have been attempts to radicalize the population at large – just as has happened in Europe. This is lead, over the years, to claims of an independent Uyghur homeland. Two violent, short lived and relatively small Uyghur Khanates existed in the region in the past, both run by local warlords. The First East Turkestan Republic was based around the Kashgar region and existed for just six months between 1933 and 1934. The Second East Turkestan Republic was based in the northern Altai region of Xinjiang over 1,300 km distant from Kashgar and existed during the upheaval of World War Two between 1944 and 1949. Neither covered extensive areas and certainly not significant parts of Xinjiang Province.

However, these claims to a Uyghur Republic, coupled with a rise in Islamic terrorism have led to a number of Uyghur related terrorist incidents in China, including bombings in several cities, attacks on police stations, and an aircraft hijacking incident. According to the terrorism tracker Fondapol, attacks by the Taliban in China and Asia rose from close to zero in 2000 to 1,301 by 2017, causing 6,510 fatalities. A Chinese crackdown has meant there have been no similar incidents, at least in China, since 2017.

Meanwhile, in comparison, the United States invasion of neighboring Afghanistan, which began in 2001 and ended just six months ago resulted in an upsurge of regional terrorism and resulted in, according to the US Watson Institute, an estimated 241,000 people being killed in Afghanistan and Pakistan. More than 71,000 of those were civilians. Faced with statistics like that, it becomes harder to disengage the impact of the US presence in Afghanistan with the Chinese approach. This is especially ironic given that the US and the West largely have ceased giving aid to the Afghanistan people, and have essentially abandoned them. Both Presidents Xi and Putin have called out for international aid to the country. Claims of genocide therefore may be perhaps more correctly viewed in terms of what sparked the upsurge of regional Islamic violence to begin with – and should be taken in the context of Chinese security concerns, as opposed to the destruction of a culture. The question to ask is whether claims of a China genocide are in fact attempts to deflect attention away from the US’s campaign on the War on Terror. However, if the term ‘Genocide’ was expanded once again to include ‘abandonment of protection’ and ‘deliberate withdrawal of humanitarian aid’ then perhaps the West might look to its own shortcomings in Afghanistan than attempt to deflect attention away from them by pointing fingers at Beijing’s Islamic security issues.

The Taiwan issue

Beijing has been highly critical concerning recent comments made by the Taipei Government concerning the fact that it regards itself as an independent, democratic Government. However, Taiwan has struggled to make diplomatic headway since 1971 when the United States broke off relations and recognized China, and it is not part of the United Nations, WHO and most other global institutions. Instead, it survives in a diplomatic grey area, with unofficial ‘representative offices’ supposedly engaged in trade being the main political forum for global engagement. Some 50 countries of the total UN number of 193 maintain these. These relationships wax and wane yet remain roughly the same in terms of numbers. Lithuania was the latest country to establish a Representative Office in Taiwan, while Nicaragua has just closed its Taiwan mission and opted to recognize China instead.

Taiwan has the farthest flung and most remote diplomatic relations in the world, with the average distance between Taiwan and a country it has formal relations with being 14,772 km – one way.

When mainland China began to open up its economy in the early 1990’s the Taiwanese economy and overall standards of living in Taiwan were superior to China. However, like China it was not especially democratic, with the ruling Kuomintang possessing a stranglehold over Taiwanese rule. In fact, although Taiwan has elections, it lurches from the current ‘Democratic Progressive Party’ in recent years back to the Kuomintang. The former are pushing a Taiwanese national identity as separate from China, even though 95% of Taiwan’s population is Han. The DPP view their difference as being democratic as opposed to China’s One-Party State, although it should be pointed out that within that, internal democratic procedures do apply. The Kuomintang on the other hand view the Taiwanese as Chinese and although have political differences with Beijing are more aligned in terms of political stability.

However, the current on-going battle between these two parties for governance of Taiwan has not been especially kind to its economic development. During the ten-year period 2010-2020, Taiwan’s GDP grew by 39.22%. Hong Kong, a relatively comparable market, yet semi-democratic Chinese territory saw its growth rate climb during the same period by 51.75%. (data from Statistica).

In fact, while Taiwan’s population at 23.41 million is three times larger than Hong Kong’s 7.5 million, its GDP is about double that of Hong Kong’s, while Hong Kong’s actual GDP per capita is US$17,000 higher than Taiwan’s per annum at US$49,036 against US$32,123. Put simplistically, Hong Kong is today rather more productive than Taiwan.

The change has been in the political arena and moves to align Taiwan with a version of democracy and dependance on US ‘values’ as opposed to China’s model.

From the perspective of Taiwan’s somewhat fractured political base, and the hard economic data, it would suggest Taiwan’s progress under this system is rather lagging.

There are additional problems with what the Taiwanese President means when promoting a separate, Taiwanese identity. With the takeover of the island in 1945, the fleeing Republicans surging into the island have seen the actual indigenous population of Taiwan now shrunk to just 2% of the total population. The vast majority of Taiwanese are Han and share the same culture as mainland China.

Claiming a national identity is additionally problematic when one considers the contents of the three different National Museums in Taipei. Most of the contents are not of Taiwanese origin but were looted from mainland Chinese cities by the Kuomintang during the Civil War and were shipped back to Taiwan. The ‘national culture’ on display in these museums is of mainland Chinese, not Taiwanese origins – it represents the world’s largest theft of cultural items and subsequent rebranding of cultural history from one people to another, ever.

The purpose of why Taiwan exists and the point of it must therefore be open to question. With ‘democratic values’ enough to gain a seat at the US Summit for Democracy when a voting share of just marginally over a third asked to be ruled by the current government makes Taiwan’s claim to independence and being representative of the people very tenuous. No attempt has been held to hold a referendum on the matter. The assumption is that the end to the Chinese Civil War 76 years ago is the defining statement of Taiwanese intent. But is it?

The lagging behind of Taiwanese growth over the past decade suggests that the chopping and changing of differing political opinions – a democratic ‘right’ – hasn’t actually been brilliant for the Taiwanese economy is another pointer – although it remains a stick with which Washington likes to use to belittle Beijing.

The questions that need to be asked are less “Democracy” as the only way ahead, but what types of democracy there are and what works best under different conditions. The United States isn’t a full democracy, it is heavily influenced by unelected business interests. The United Kingdom isn’t a full democracy, it has an unelected House of Lords and a hereditary Monarch that oversee the popular vote. The European Union has imposed its will on Sovereign nations. China may have a One-Party system, but within that structure, decisions are made by a democratic process involving some 5,000 academics, politicians, analysts, and businesspeople.

At the US ‘Summit for Democracy’ last November, Taiwanese Minister Audrey Tang showed a map that indicated civil rights. Taiwan was ‘green’ and the only ‘open democracy in Asia’. All other Asian nations were shown as being “closed,” “repressed,” “obstructed” or “narrowed.” China, Laos, Vietnam, and North Korea were all colored red and labeled in the same category as “closed.” Quite what countries such as Japan, South Korea, Singapore, and s n have to say about that is unclear. Do China, Laos and Vietnam really face the same repressions as North Korea?

The US State department commented “We valued Minister Tang’s participation, which showcased Taiwan’s world-class expertise on issues of transparent governance, human rights, and countering disinformation.”

Bonnie Glaser of the German Marshall Fund of the United States said concerning Taiwan’s inclusion at the event that “It seems to me that a decision was made at the outset that Taiwan should be included in the Summit for Democracy, but only in ways consistent with U.S. policy.”

So, what is the point of Taiwan? It’s a question that requires some thought and analysis before the island can truly get into stride and cease having to deal with the absurdity of its diplomatic allies being 14,000km distant. Are Taiwan’s democracy, its culture, economics, history, freedoms, and nationality really different, or superior to that of the Chinese? Or is it in reality a client of the United States, from whom, according to Bloomberg, it purchased US$750 million worth of weapons systems in 2021?

It is an interesting perspective, not least because last week, a number of US Senators voted to change the name of the US trade office with Taipei, to the US trade office with Taiwan, in full knowledge that this will rile Beijing even further, increase tensions. Is it a coincidence that in doing so, this permits the avenue of further weapons sales to the island to open ever wider?

The Ukraine issue

On the other side of Eurasia, Russia has been making noises about Ukraine and been positioning troops to the north, east and south of the country. This has been met with alarm in Europe and the United States, who have been wooing the country West since the collapse of the USSR in 1991. Today, that has manifested itself with several prior Soviet countries joining both the EU and NATO, with Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, Bulgaria and Romania all part of the NATO axis. Ukraine though represents a step too far, for Moscow at least, as the nearest point from the Ukraine-Russia border to Moscow is just 450km. Moscow knows that the US is about to deploy hypersonic missiles capable of flights at the speed of Mach5 and above. Consequently, it wants the expansion of NATO eastwards halted and pushed back.

The United States meanwhile has been demonizing Russia to the EU over energy security issues, stating that it is too dependent on Russian gas and that this represents a risk. Moscow could, the perspective goes, just turn the gas supply off – although this has never occurred. Naturally, there is a ready alternative solution – for the EU to buy gas and energy from the US and its allies instead. However, it is also true that this would be both more expensive and less eco-friendly – US gas would have to be shipped to Europe – while new pipelines constructed (with the assistance of US contractors) built to supply the EU from US friendly allies in the middle east. To put this into further perspective, the US has stated it would place ‘the Mother of all sanctions’ on Russia – including the termination of the gas supplies, and disconnection from the SWIFT global payments network – should Russia invade Ukraine. Judging by the rhetoric issued from Washington, it seems on one hand that it is almost willing for Russia to take that step. Putin so far has resisted. I suspect that will be the long-term game, with Russian troops remaining close to the Ukrainian borders until the EU gets fed up with the cost of maintaining the additional US forces now in Eastern Europe and the uncertainty of gas supplies.

But either way, one cannot dismiss that President Putin is right to be concerned about NATO missiles so close to Moscow. After all, President Kennedy objected over the USSR deploying missiles in Cuba. Yet Russia is deemed the aggressor. Is it? Or does the US want the EU contract for gas and military supplies and is talking up the Russian dangers, while at the same time goading it into attacking Ukraine by creating a problem by placing missiles within easy reach of Moscow?

The Democratic issue

The main issue used to beat up Russia and China is the nature of their political systems, with Russia a semi-autocratic democracy and China a one-party state. The United States has been very keen to play up these distinctions in recent years, holding the ‘Summit for Democracy’ last year and often referring to ‘democratic values’. Yet in doing so in creates divisions, to the extent that Moscow has recently complained to the degree of this influencing global affairs. Both Presidents Putin and Xi have spoken about the diminishing of the existing global rule of law, while the United States wishes to ‘uphold the rule of law’. Yet there are subtle distinctions between the two that should not go unnoticed. China and Russia are great believers in the global institutions that were put in place at the end of World War Two, an event that wreaked much destruction upon both (but left the United States, with the exception of Pearl Harbor, largely untouched). Beijing and Moscow are permanent members of the United Nations Security Council, and in common with the other three members, France, the United Kingdom and United States, can veto decisions if they feel they are not in the global interests. This itself is a form of limited democracy and prevents attempts to subvert the process and replace it with a dictating form of fascism. If consensus cannot be reached – more debate and discussion is required.

Yet it has become apparent that latter day United States thinking now views these mechanisms as potentially unhelpful towards its own interests. These also involve global institutions such as the World Bank, WTO and WHO – the latter of whom the United States was seriously behind in making its committed payments to at the time that the Covid pandemic hit.

Instead, what has been happening is that rather than go through dispute processes at these institutions, Washington has increasingly viewed them as obstructionist and of getting in the way of US policy.

Instead of trade disputes being heard at the World Trade Organisation, Washington finds it easier and more effective to get its way by unilaterally imposing sanctions and motivating its allies to follow. Global financing needs via the World Bank have tended to focus on the interests of US foreign policy, with non-compliant countries omitted from beneficiary loans and aid. Cutting Russia off from SWIFT – and the global financial system – no longer requires a global vote at the UN – as the US has the keys.

The United States resigned from the World Health Organisation – in the middle of a global pandemic! (It has subsequently rejoined).

Are these behaviours that are consistent and taken after having listened to all perspectives? Or are they unilaterally now taken by just one power with everyone else having to follow suit? This is what Putin and Xi refer to when they mention the destruction of the global rule of law.

Both China and Russia are united in preserving these global institutions, and recognize that although flawed, they have largely kept the world order in place since 1949. It is the United States, not Messrs. Putin or Xi, who wish to replace this with a unilateral system based solely on US foreign policy. This means that Washington is using the premise of democracy as a means to promote what is in fact a form of dictatorship in its own right: you can all call yourselves democratic – and go through the motions, as long as you elect a US friendly government over which we will call the shots.

Presidents Putin and Xi, in recognizing this, are being demonized, with quite deliberate stress points being put into position to sell their ‘aggressiveness’ to the rest of the world. Taiwan. Ukraine. Uyghur Genocide. Dictators. More attempts to point fingers and to cast them as ‘baddies’ will undoubtedly follow. But is it a great idea to allow the United States a free hand in running the brave new world? And if so, exactly what form of democracy would be permitted by Washington?

That is the question that China and Russia are both asking – and it is a valid point to make.

Meanwhile, I should state that I am a fan of democracy. But it is a very fragile system and prone to weaknesses. Democracy ceases to be democratic however when just one country wishes to operate it with all others following a singular lead. Today’s danger is that is exactly what the world is walking into, and I do not believe the American version is the ideal.

The China-Russia Relationship

China and Russia are joined together by a 4,133km border, mainly between Northeast China and Russia’s Far East. That is roughly double the length of the Russian border with the European Union. The Russian Far East now receives about 32% of all FDI into Russia, and with fast developing city ports such as Vladivostok is both the starting and end point for the Trans-Siberian railway and the Northern Sea Passage. Although it will be another decade or even more until the latter becomes fully operational, the development of this maritime route is already underway, with massive infrastructure developments, some with joint Chinese investments taking place all around the northern Russian coastline. Parts of this, especially the Yamal Peninsula, have intense Chinese interests as the source of the various Siberian gas pipelines being fed through to China. Others are developing as commercial ports all the way West along to Northern Europe, with interconnecting rail and airports also part of the mix.

Bilateral trade is now projected to reach US$250 billion by 2025. To put that into context, this is about 45% of China’s bilateral trade with the United States, but to a population also about 45% of that of the US. Or to put it another way, by population demographics, Russia-China trade per capita will shortly be to the same volumes as China’s trade with the United States citizenry.

Another element not yet apparent in China-Russian trade volumes is that China signed off a Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in September 2018. At present this is non-preferential, meaning no tariff reductions have been agreed. But as and when they are, bilateral trade will receive another boost. That could also eventually lead to Russia joining the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP) free trade agreement further down the line. This fits with current trade thinking – the EAEU is also discussing free trade potential with ASEAN, which is also part of the RCEP agreement, while Japan and South Korea, again RCEP members are traditional Far East Russian markets.

Within this trade sphere are likely to be collaborations with China on hi-tech issues such as solving the semi-conductor development issue and exploiting reserves of the required rare earths and related commodities.

Militarily, the two are already part of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), which is taking over the mantle of regional security in Central Asia, and specifically in Afghanistan following the departure of the United States and NATO. Settling down Afghanistan and radical Islam will continue to be a focal point for both over the coming decade. They will not want to be distracted by military conflicts either to the West in Ukraine or to the East in Taiwan, regardless of Western perceptions that they do.

There are other regional and global partnerships both are exploring. India remains wary of China but is developing closer ties with Russia. Over time, and perhaps influenced by collaborations within the SCO (India is a member) rhetoric between Beijing and Delhi may soften. With India a major presence in Africa, Delhi may also be able to take advantage of Moscow and Beijing’s increasing trade ties in the Middle East and Africa.

In these ways, Beijing and Moscow will seek to balance Washington’s attempts to push through a US version of global hegemony described as ‘democratic values’ and currently being purchased by Europe.

This axis also seeks to minimize any efforts by the United States to push the world into a new Cold War and taking the EU with it on one side, and China and Russia on the other. Should this happen – and some US hawks such as the Trumpian groups seem bent on achieving this – then at least Beijing and Moscow can minimize the impact felt upon their own economies, although both undoubtedly see such an outcome as a disaster.

Ultimately the question for Europeans to ask is to what extent they can also balance the China-Russian Eastern axis against the US ‘Western’ axis – without sliding too far down along either one side or the other.

Related Reading

About Us

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists British and Foreign Investment into Asia and has 28 offices throughout China, India, the ASEAN nations and Russia. For strategic and business intelligence concerning China’s Belt & Road Initiative please email silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com