India Becomes Transportation Hub Of China’s Belt & Road Initiative As Co-Investments Increase

Actual developments far different from official policy, media hype and recent events suggest concerning China-India connectivity

Op/Ed by Chris Devonshire-Ellis

China-India relations have been hitting the headlines recently, with skirmishes in the Galwan Valley near Ladakh leaving numerous soldiers dead in a fairly serious outbreak of violence. Both sides have agreed terms to back off from any further aggression in the region.

China-India relations have been hitting the headlines recently, with skirmishes in the Galwan Valley near Ladakh leaving numerous soldiers dead in a fairly serious outbreak of violence. Both sides have agreed terms to back off from any further aggression in the region.

Much has also been made of recent Indian regulatory issues being anti-China investment in tone. However, these fail to read the small print. India is in fact the current largest recipient of announced Chinese outbound investment right now, which has risen from 1.8 percent of China’s total outbound investment spend in 2018, to 5.6 percent in 2019, and is currently at 7 percent this year to date.

While journalists make a big play about India not signing up to China’s Belt & Road Initiative (due to issues concerning territorial disputes in the states of Jammu and Kashmir and Arunachal Pradesh), the reality is that Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi and Chinese President Xi Jinping have previously made reference to a “One Hundred Year Plan”, intended to help both countries reach their potential in Eurasian trade. While the Indian Prime Minister has not yet accepted this proposal, it remains open for discussion.

In October last year, President Xi met with Prime Minister Modi in Chennai, their second informal summit in 18 months. A key issue discussed during the meeting was related to trade, including the invitation of Indian pharmaceutical and information technology (IT) companies to conduct investment/cooperation in China as a way of addressing the trade deficit between the two countries.

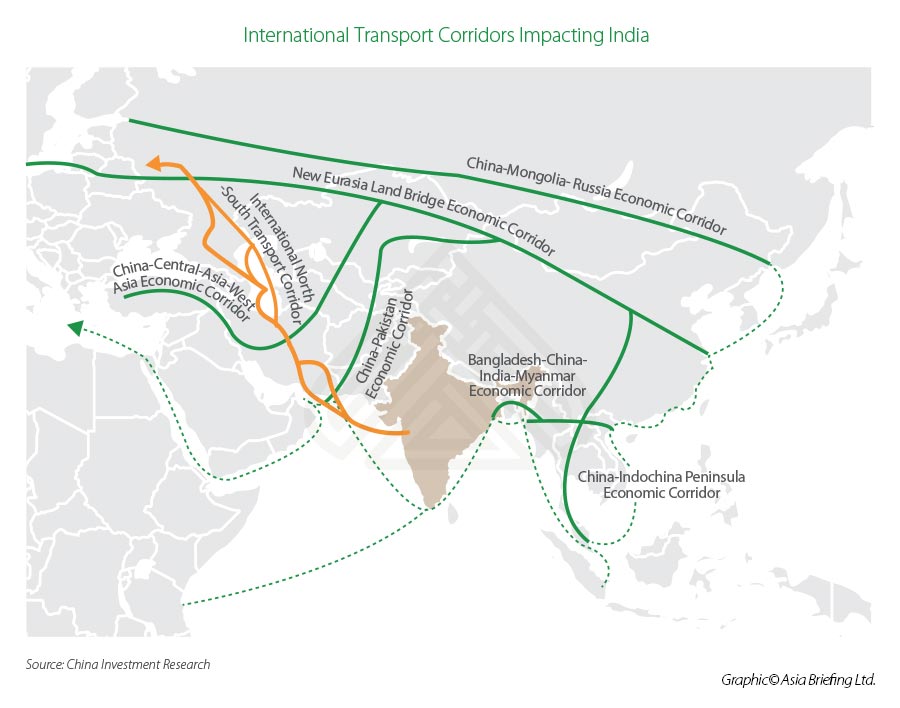

There are other considerations too. Both countries have been concerned about the impact of the United States use of sanctions and mis-use of the US dollar to punish countries that do not do as Washington wants. Yet this includes clients of both China and India, most notably Iran and Russia who have huge business and investment influence in Beijing and Delhi. China and India are both members of the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), whose influence can be seen in the map below.

As I pointed out in the article Ruble, Yuan & Rupee To Dominate Future Belt & Road Eurasian Transactions numerous members of the SCO are actively looking to conduct trade in national currencies and ditch using the US dollar. It will only be a matter of time before India becomes more actively involved in holding larger deposits of RMB Yuan as a reserve, and the Bank of India has long provided settlements in RMB Yuan in a collaboration with the Bank of China. Meanwhile, just last week India received a US$750 million loan from the China-backed AIIB to assist with Covid-19 issues. The countries are becoming more trusting and using of each currencies than ever before.

Xi offered such a collaboration and stated the priorities should be to map out a hundred-year plan for their bilateral relations from a strategic and long-term perspective. These include the establishment of friendly ties between Fujian Province and the state of Tamil Nadu, as well as between the cities of Quanzhou and Chennai. Following his meetings in India, President Xi subsequently met with Nepal’s President Bidya Devi Bhandari. This was the first visit by a Chinese President to Nepal in 23 years. One of China’s goals is to help Nepal realize its dream of becoming a land-linked country from a land-locked one, thus, infrastructure building is critical.

These are not the sole initiatives and inter-connectivity projects underway. We examine how India can cleverly manage to be both unofficially “in” and officially “out” of China’s Belt & Road Initiative as explained in the following sections.

The Bangladesh-China-India-Myanmar Economic Corridor (BCIMEC)

What is effectively occurring with BCIMEC is a Chinese-Indian collaborative effort to rebuild the Silk Roads from Eastern India into Western China – a revamp of the old Stilwell Road that sees Yunnan province connected with Ledo, in India’s Assam state, via Myanmar and Bangladesh. We wrote about that from the Yunnan perspective ten years ago.

The BCIMEC is a 2,800 km connectivity corridor that links Kunming in China, with Kolkata in India via Mandalay and Dhaka.

The Bangladesh Belt and Road

In 2016, Bangladesh and China signed 27 agreements for investments and loans worth around US$24 billion during President Xi’s visit to Dhaka that year. Together with the US$13.6 billion invested in earlier joint ventures, Chinese investment in Bangladesh now totals about US$38 billion, making China Bangladesh’s single largest investor and Bangladesh the second largest recipient of Chinese loans under BRI in South Asia.

Pakistan, a beneficiary of about US$62 billion of Chinese BRI commitment, has a population of 200 million, while Bangladesh, with US$38 billion of BRI commitment has a population of 166 million. The China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) may have taken up a lot of the attention, but its sphere of connectivity runs far wider – and indirectly impacts India.

In Bangladesh, much of the infrastructure is close to being completed, such as the Padma Bridge, on track to open next year, and when completed, will be the largest bridge in the country. Then there is the Payra Seaport, a US$15 billion investment to create a deep water facility. Extensive dredging is taking place in Bangladesh’s notoriously silted water, and current progress is slow. This is also hindering the development of Bangladesh’s 2,000 MW power plant development, but progress is being made.

China and Bangladesh have been negotiating and have now decided to proceed with a 900 km highway to connect Chittagong and Kunming through Myanmar (the Stilwell Road mentioned earlier, and discussed for over a decade), and therefore lowering shipping costs/shipping risk. This also fits with their joint initiative of improving Chittagong port infrastructure.

Bangladesh and China are also developing a Chinese Economic and Industrial Zone (CEIZ) with an existing footprint of 781 acres close to Bangladesh Port, although a China-built tunnel is critical to its connectivity with Chittagong. The CEIZ will specialize in chemicals, automobile assembly, garments, and pharmaceuticals.

Bangladeshi communications are also getting a major upgrade, although 4G is operational in Dhaka, most of the country still utilizes 2G. Huawei though has operated in Bangladesh for years and the Bangladeshi government is comfortable with that relationship, also realizing that putting in place a 5G network will mean investment capital and trade will follow. Bangladesh, with its youthful population, is focused on building a digital economy, similar to China.

The Myanmar Belt and Road

In January this year, China and Myanmar signed 33 agreements to accelerate the development of the China Myanmar Economic Corridor (CMEC), which was officially launched in 2018. While none of these were new, they brought new focus, including 14 of the MOUs that aimed to strengthen collaboration in the infrastructure sector: Kyaukphyu (deep water seaport) and SEZ, the Muse/Mandalay Railway, which at 431 km links Yunnan to Mandalay; the Three Border Economic Cooperation Zones; the Myitsone Hydropower project, which has been blocked since 2011 but now restarted; the Myitkyina Economic Development Zone, in addition to the New Yangon Development, a new city project in Myanmar’s commercial capital.

The Nepal Belt and Road

During the China-Nepal meetings, the two countries signed 20 cooperation agreements, one of which was a pledge of US$500 million in financial aid over the next two years. They also agreed to a 70 km extension of the existing Qinghai-Tibet railway to Rasuwagadhi, then onto Kathmandu and Lumbini (birthplace of the Buddha). This represented a small component, with much lower financing amounts that had been pre-empted a year earlier by a China pledge to US$8.3 billion for a series of infrastructure projects, most of which was around the construction of trans-Himalayan connectivity to include ports, 540 km of highways, operational by 2025, and to include rail, air, and communications. Ultimately, these will link into Uttar Pradesh state in India and could conceivably become a Nepal-India-China corridor. Nepal also has 84,000 MW of hydropower potential – of which 43,000 MW could be economically viable. This energy can be sold to countries with power shortages, such as Myanmar, Laos, and the rest of Southeast Asia.

The New International Land-Sea Corridor

The New International Land-Sea Trade Corridor (ILSTC) is a trade and multimodal transport corridor jointly built by the western Chinese provinces and the ASEAN countries. The ILSTC treats Chongqing and the Beibu Gulf ports of mainland China, Hong Kong, and Singapore as different transport hubs through which it attempts to link the western provinces of China with the Indochina Peninsula, the ASEAN region, as well as the BCIM. As of Q1 2019, eight of China’s western provinces, autonomous regions, and municipalities, including Chongqing, Guangxi, Guizhou, Gansu, Qinghai, Xinjiang, Yunnan, and Ningxia, had joined the ILSTC. Shaanxi joined in May 2019.

With Chongqing as its center, the corridor offers an alternative for western Chinese provinces and autonomous regions shipping goods otherwise from the east coast. It is also a strategic channel connecting the “Belt and Road” Initiative and the Yangtze River Economic Belt. International trade among the ASEAN countries, Central Asia, and the EU can also be improved by the existing China Railway (CR) Express service from western Chinese cities.

Impact on India

This means that India is set to become a focal point for two major infrastructure and trade routes with China, and by proxy, a major (unofficial) player in China’s Belt and Road Initiative. This has huge implications for regional trade between China and India as well as with Bangladesh, Myanmar, and Nepal.

These plans will further connect India with Bangladesh, India, and Nepal, therefore giving a southern and northern route from India overland to China; a southern route via Bangladesh and Myanmar; and a northern one from Uttar Pradesh through Nepal, heading east and through Tibet joining the Chinese national rail network. They also link the country, and especially its under-developed eastern seaboard, with the massive potential of the ILSTC routes, meaning matching infrastructure developments can be expected to arise along the east coastal and Coromandel coasts of India.

Further north, I have been to the southern part of Tibet, on the border with India, at the confluence of the Brahmaputra River overlooking Arunachal Pradesh. The Chinese infrastructure is all in place, all that needs to happen is for India to reciprocate. That is likely to occur when India’s Senior Generals, long educated in the China-India border war in 1962 and the China threat for decades, start to retire and their influence wane. That is happening now. Southeastern Tibetan cities, such as Nyingtri are waiting and available to receive goods and ship them from China to India via Lhasa and vice versa.

These actual on-the-ground developments are far away from the official line, which manifests itself for public consumption in Indian headlines showing that India officially declining to attend Belt & Road Initiative meetings hosted by China. India not being part of China’s Belt & Road Initiative is the public perception, aided by the Government in order to prevent political and public controversy.

In fact, China and India have agreed much more than developing infrastructure and trade routes. The hardware done, and being built, has seen bilateral trade developments take place. Here, Xi and Modi have essentially agreed on trade, with India pharmaceuticals being allowed access to the China markets, and China being given access to Indian tech.

Much has been made of the recent Indian revised FDI policies, with all projects from India’s neighboring countries, which include Bangladesh, Myanmar, Nepal, and China, all being required to have new projects vetted by New Delhi prior to approval. This additional step has caused confusion in some quarters and been seen as a form of protectionism. In fact, it can also be viewed as a matter of obtaining clarity and instigated in order to provide a better coordinated program of regional integration as highlighted above. It is a situation we touched on in our recent article How Will India’s Revised FDI Policies Impact Upon Chinese Investment?

India and international land/sea transport corridors

However, it is also true to say that some of the India infrastructure initiatives bypass Chinese infrastructure, at least for now. While India will make full use of the eastern integration, to the west it is a rather different matter. China has massively invested in the south Pakistan Port of Gwadar, as part of its massive CPEC corridor. India, wary of both China and Pakistan’s intentions, and knowing there are very likely to be disruption created to Indian shipping using the Gwadar facilities, has instead linked up west bound with Iran’s North-South International Transport Corridor at the Iranian Port of Chabahar, and is a significant investor. The distance between Pakistan’s Gwadar and Iran’s Chabahar Port is just 72 km; both are deep water facilities.

It should also be noted that India, Pakistan, and Iran are members and observers of the Beijing-initiated Shanghai Cooperation Organization and have a formal discussion platform to determine trade and connectivity issues away from the spotlight of what can be tense regional politics.

The International North-South Transport Corridor (INSTC)

From Chabahar, Indian goods can continue via sea further west, or join the International North South Transport Corridor (INSTC), which heads north before offering options east, and reconnecting India with Afghanistan and Central Asia, and due north, where it connects with Russia and its trans-Eurasian railway.

The implications for India are immense. With sea and rail connectivity to the west, and the same to the north, east, and south, the country is developing as a massive Belt and Road Initiative hub – all without actually being part of it. That has been some trick for Prime Minister Modi to pull off – but without doubt it promises to herald a new wave of investment into the country.

We are grateful to Henry Tillman and China Investment Research for a large part of the intelligence provided. China Investment Research are part of Grisons Peak Services, a UK-based consultancy practice.

This article previously appeared on Silk Road Briefing under the title, “China’s Latest Outbound Investment Target…And the Winner is India“ and has been updated to reflect recent events.

Related Reading

- Has India Lost its Free Trade Mojo? Or Will Delhi Substitute the RCEP for the EAEU?

- India Joins Shanghai Cooperation Organization

Due Diligence for Foreign Companies in India

Due Diligence for Foreign Companies in India

Foreign companies investing in India are advised to do a due diligence check, especially if entering into a joint venture, merger and acquisition, or partnership. The due diligence process uncovers critical information relating to the business and its management, thus helping investors decide if they should go ahead with their financial deal, or negotiate better terms and conditions, or withdraw their interest from the target entity or deal.

About Us

Dezan Shira & Associates advise clients on Belt & Road Initiative matters as well as investment into Asia. The firm has offices throughout China, India and the ASEAN region and is well positioned to advise clients on strategic as well as trade legal, operational, tax and on-going issues. Please contact us at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com