Understanding The China-Russia Trade, Investment & Economic Relationship In The Context Of The Ukraine Conflict

Surging Trade As Bilateral Relations Grow Closer

China and Russia have grown increasingly close in recent years, including as trading partners, in a relationship that brings both opportunities and risks as Russia reels from tough new sanctions led by the West in response to its invasion of Ukraine. Total trade between China and Russia jumped 35.9% in 2021 last year to a record US$147.9 billion, according to Chinese customs data, with Russia serving as a major source of oil, gas, coal and agriculture commodities, and running a trade surplus with China.

Since sanctions were imposed in 2014 after Russia annexed Ukraine’s Crimea, bilateral trade has expanded by more than 50% and China has become Russia’s biggest export destination The two were aiming to boost total trade to US$200 billion by 2024, but according to a new target unveiled last month during Russian President Vladimir Putin’s visit to Beijing for the Winter Olympics, the two sides want bilateral trade to grow to US$250 billion.

It should be noted that the two men enjoy close personal relations, as evidenced at meetings and anecdotes the pair shared with the floor at the 2018 St. Petersburg International Economic Forum, with tales of Putin serenading Xi Jinping at the piano during private gatherings at Putin’s Dacha in Moscow. The relationship goes deeper than pure business and has manifested itself in an understanding of global geopolitics and especially a growing distrust of the United States. Shared experiences of sanctions and tariff wars with Washington has resulted in collaboration and planning to offset anticipated US actions.

As sanctions against Russia mount, China could offset some of its neighbor’s pain by buying more but would also be wary of running foul itself of potential sanctions. We highlight key areas of trade cooperation between China and Russia as follows:

Exports of Russian oil and gas to China have steadily increased.

Russia is China’s second-biggest oil supplier after Saudi Arabia, with volumes averaging 1.59 million barrels per day last year, or 15.5% of Chinese imports. About 40% of supplies flow via the 4,070-km (2,540-mile) East Siberia Pacific Ocean (ESPO) pipeline that was financed by US$50 billion in Chinese loans. Russia is also Beijing’s No. 3 gas supplier, exporting 16.5 billion cubic metres (bcm) of the fuel to China in 2021, meeting about 5% of Chinese demand. Supplies via the Power of Siberia pipeline, which is not connected to the network of westbound Russian gas pipelines, began in late 2019 and are due to rise to 38 bcm a year by 2025, up from 10.5 bcm in 2021, under a 30-year contract worth more than US$400 billion. Russia aims to build a second gas pipeline, Power of Siberia 2, with capacity for 50 bcm a year to run via Mongolia to China. Russia was also China’s No. 2 coal supplier in 2021. Last month, Putin unveiled new Russian oil and gas deals with China worth an estimated US$117.5 billion.

These additional figures are significant in understanding the effectiveness of Western sanctions upon Russia. Russia’s bilateral trade with the European Union is 2021 was Euros 247.8 billion, with Russian exports worth Euros 158 billion. Of that, about Euros 110 billion was in oil and gas, leaving Euros 48 billion in other trade such as autos, machinery and so on. That can be swallowed up within two years assuming the China[1]Russian revised trade figures to US$250 billion are realized by 2024 – as is the stated intent.

Russia already sends gas to China via its Power of Siberia pipeline, which began pumping supplies in 2019, and by shipping LNG. It exported 16.5 billion bcm of gas to China in 2021. The Power of Siberia network is not connected to pipelines that send gas to Europe, which has faced surging gas prices due to tight supplies, one of several points of tension with Moscow. Under plans previously drawn up, Russia aims to supply China with 38 bcm of gas by pipeline by 2025.

Separately, Rosneft, headed by longstanding Putin ally Igor Sechin, signed a deal with China’s CNPC to supply 100 million tonnes of oil through Kazakhstan over 10 years, effectively extending an existing deal. Rosneft said the new deal was worth US$80 billion. The agreements boosted the ruble and the Russian stock market, including shares in Rosneft and Gazprom.

It is significant that after the Moscow Stock Exchange was suspended for three weeks after Russian military rolled into Ukraine and Western sanctions were imposed on the first day on reopening on March 21, Russian stocks rose by 11% in early trading before settling down to daily gains of 4.4%. However, the new deal with Beijing does not impact on Russian gas supplies that were otherwise bound for Europe, as the Rosneft deal involves gas piped from the Pacific island of Sakhalin and is not connected to Russia’s European pipeline network.

Gazprom said in a statement it planned to increase gas exports to China to 48 bcm per year, including via a newly agreed pipeline that will deliver 10 bcm annually from Russia’s Far East. Under previous plans, Russia aimed to supply China with 38 bcm by 2025. The announcement did not specify when it would reach the new 48 bcm target. Gazprom, with foreign partners which previously included Shell, already produces more than 10 million tonnes of LNG / year in Sakhalin. That raises the possibility that should the political situation later change, Russia could once again supply gas to the EU. We suspect demand for cheaper prices in Europe will eventually put this proposal back on the negotiating table despite US attempts to prevent it.

It should be noted however that there may be a limit to China’s patience concerning the Ukraine conflict, which is disabling part of its own supply chains and interfering with the preferred Chinese modus operandi of ‘sustainable development.’ To illustrate growing discontent, Sinopec canceled in late March a proposed US$500 million investment with Russia’s Sibur, its largest petrochemical producer for a 40% stake in a facility in East Siberia. Putin will have noticed.

Other Commodities

In 2019, China allowed the import of soybeans from all regions of Russia, and the two countries signed a deal to deepen cooperation in soybean supply chains, which saw more Chinese firms growing the beans in Russia. Soybean exports to China stood at 543,058 tonnes last year and are expected to reach 3.7 million tonnes by 2024.

In 2021, China approved beef imports from Russia, while in March this year, Beijing allowed imports of wheat from all regions of Russia, removing previous restrictions. Other food exports from Russia to China include fish, sunflower oil, rapeseed oil, poultry, wheat flour and chocolate.

China is also a huge buyer of timber from Russia’s Far East, with imports of timber and related products worth US$4.1 billion last year. In the other direction, China sells mechanical products, machinery and transport equipment, mobile phones, cars, and consumer products to Russia.

Chinese exports to Russia stood at US$67.6 billion last year, up 34% with this likely to be a growth market as Russia replaces previously EU sourced products with those from China and Asia.

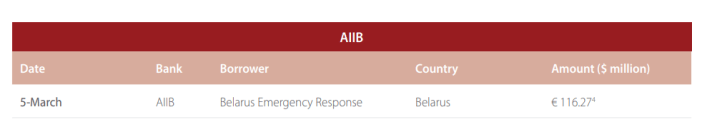

There are yet to be implemented trade agreements that could be fast tracked to speed Russia-China bilateral trade faster and further. Beijing signed an as yet non-preferential (ie: no tariff cuts) Free Trade Agreement with the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU) in 2018, as and when tariff cuts can be agreed, the impact of China-Russian free trade would be enormous. Other EAEU members include Armenia, Belarus (itself under severe Western sanctions), Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan.

Investment/Chinese Financing

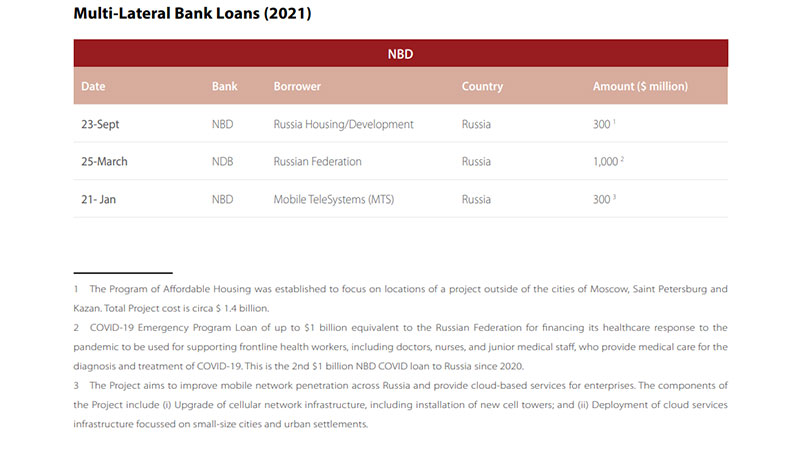

Western sanctions have forced Russia to look towards China for investment opportunities in recent years, and Chinese state banks have helped Russia finance everything from infrastructure to oil and gas projects under China’s Belt and Road Initiative. Russia is by far Beijing’s largest recipient of state sector financing, securing 107 loans and export credits worth US$125 billion from Chinese state institutions between 2000 and 2017 (source: College of William and Mary’s AidData).

China and Russia began using their own currencies to settle bilateral trade in 2010 and opened their first currency swap line in 2014, which they renewed in 2020 for 150 billion yuan over three years. RMB Yuan settlements accounted for 28% of Chinese exports to Russia in the first half of 2021, compared with just 2% in 2013, as both countries seek to ease reliance on the dollar while developing their own respective cross-border payment systems. Chinese currency accounted for 13.1% of the Russian central bank’s foreign currency reserves in June 2021, compared with just 0.1% in June 2017, with Moscow’s US dollar holdings dropping to 16.4% from 46.3% in the same period. Russia now carries no dollar reserves in its sovereign wealth fund – yet has the world’s largest reserves of gold. It is becoming increasingly significant that the US dollar has lost 80% of its value against gold over the past 20 years; with China and Russia looking to further de-dollarize, the greenback could come under increasing pressure over the coming years.

Bilateral Investment – Hong Kong

At the end of 2020, Hong Kong was the third most popular destination in Asia for Russian investment, behind Singapore and Thailand, with a total FDI stock of US$364 million. Hong Kong and Russia signed a Double Tax Treaty in 2017, which has the effect of reducing withholding and other trade taxes, and sought to establish Hong Kong as a services base for Russian businesses accessing the mainland China and other nearby ASEAN markets.

At the end of 2020, Hong Kong was the third largest Asian investor in Russia, behind Singapore and South Korea, with a total FDI stock of US$2.5 billion, helped in part by the Russia-Hong Kong Double Tax Agreement. However, the value of FDI inward stock in Russia fluctuated during this period from approximately US$471.5 billion in 2013 to US$449 billion in 2020, with the decline due to sanctions placed on the country in 2014 due to the annexation of Crimea. Russian businesses also began to experience difficulties in establishing bank accounts in both mainland China and Hong Kong due to concerns that the United States would punish banks that did so, the emphasis being placed on a ‘safety first’ protocol of non-engagement. Due to the severity of 2022 sanctions, that viewpoint may have weakened with new routes to operational financing instead now being considered, and we are indeed now seeing an exodus of Russian businesses from both Hong Kong, Singapore and Moscow heading to Dubai.

In 2020, Russia was Hong Kong’s 21st largest trading partner worldwide (accounting for 0.5% of the city’s total trade) and its largest in CEE. Russia was Hong Kong’s 18th largest export market worldwide (with 0.7% of the city’s total exports) and its largest in CEE (35%) mostly IT/tech, while Russia was Hong Kong’s 27th largest import market worldwide (with 0.2% of the city’s total imports) and its largest in CEE (43%) – mostly energy.

Summary

It is important to understand that both Moscow and Beijing see the Ukraine issue as part of a wider struggle with the United States as what they see as a dangerous and unwelcome descent into a unipolar world ruled exclusively from Washington. Both have called for reforms at the United Nations Security Council, the World Bank for greater inclusion in global affairs to be awarded not just to them, but to larger economies such as Brazil, India, and Africa. In fact, they have instigated just this with the BRICS grouping – which by 2030 some analysts believe will be responsible for 50% of global GDP – but will be inadequately represented in global institutional mechanisms. Growing wariness – and outright unhappiness – of Washington’s use of the US dollar and the SWIFT global banking system as trade weapons are also causing greater distrust.

China and Russia can be expected to hold firm at this juncture in the face of what they perceive as American aggressiveness with the EU now just tagging along with whatever US policy suggests.

For clues however as to how this may pan out over time, it is worth pondering that as at March 2022, 146 countries globally had signed up to China’s Belt and Road Initiative.

This article was taken from the Asia Investment Research paper, “Russia’s Pivot To Asia”. This 55 page document can be downloaded on a pay-what-you-want basis (minimum US$10) from the Asia Investment Research library here.

Related Reading

About Us

Chris Devonshire-Ellis is the Chairman of Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm assists British and Foreign Investment into Asia and has 28 offices throughout China, India, the ASEAN nations and Russia. For strategic and business intelligence concerning China’s Belt & Road Initiative please email silkroad@dezshira.com or visit us at www.dezshira.com