The Afghanistan-China Belt & Road Initiative

Potential routes exist along the Wakhan Corridor and via Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, but it is Pakistani access to Kabul that looks the better option – as long as the Taliban can provide stability, develop Afghan society, and refrain from regional aggression.

International media has focused on Afghanistan these past few days and rightly so as the appalling situation left behind continues its descent into utter chaos. Little mentioned however has been the possibility of restructuring Afghanistan’s supply and trade chains after twenty years of war. While the Russians will largely provide security in the region, China will provide the financing and help build the infrastructure and encourage industrialization and trade in return for peace and security. People tend not to fight when they are in the process of transforming their lives for the better, and Beijing understands this, although much of the social problems are the Taliban’s responsibility to solve.

There are several options for China to instigate trade routes with Afghanistan. In this article I discuss the Wakhan Corridor, the finger of Afghanistan that reaches east to the Chinese border, existing trade routes via Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan, and the potential to further develop the Karakorum Highway route through the Khunjerab Pass and ultimately via Peshawar to Kabul.

The Wakhan Corridor, the narrow stretch of Afghanistan that reaches to the Chinese border with Xinjiang has often been cited as a solution with an assumption it can be opened to trade. I have been to this region. It was also the route used by Marco Polo to enter China. In this article I will discuss its history, routes used across it, infrastructure plans, the current situation and, should Afghanistan be stabilized after the Western nations ignominious retreat, the potential for the Wakhan Corridor as part of the Belt & Road Initiative, in addition to the mountainous western Pamir routes through Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan as well as the southern, Pakistan option.

Wakhan Corridor – History

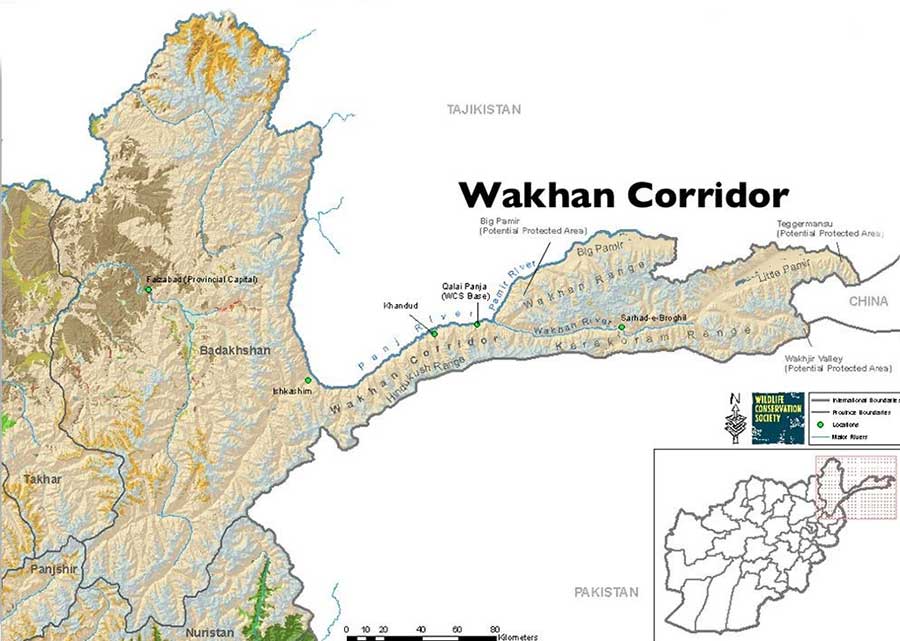

The Wakhan Corridor is a narrow strip of land in Afghanistan, extending east to China’s Xinjiang Province and separating Tajikistan from Pakistan. It runs between the Pamir Mountains to the north and the Karakoram Mountain range to the south. The Wakhan Corridor itself is about 350 km long and 13–65 kilometers wide as a natural valley between the two mountain ranges.

From this mountain valley the Panj and Pamir rivers develop and combine to form the Oxus River, which ultimately flows into the Aral Sea. A trade route through the Wakhan Valley has been used by travelers to and from East, South and Central Asia for thousands of years. Marco Polo is said to have used this route and to have stayed at Taxkorgan Fort, which is now ruined but can be seen at the Chinese village of Taxkorgan, on the Chinese border with Pakistan on the Karakoram Highway. Immediately to the east lies the Taklimakan Desert.

The Wakhan corridor was formed by an 1893 agreement between the then British Empire (British India) and Afghanistan, creating the Durand Line, acting as a buffer zone between the British and Russian Empires (now Pakistan and Tajikistan). Its eastern end bordered China’s Xinjiang, then ruled by the Chinese Qing Dynasty. The border with China stretches 92 kilometers and is characterized by unstable, slate rock with constant slippages. The entire border is marked by a barbed wire fence, with a Chinese border guard outpost at Keketuluke just 20 kilometers east of the pass. There are border crossings (discussed later) but much of the border area is impassable, prone to landslides and dangerous. Temperatures during the winter can reach -20 and include deep snow drifts.

To maintain diplomatic connections, both the British and the Russian maintained consulates in the nearby Chinese city of Kashgar until the 1930’s.

Politically, today the corridor is in the Wakhan District of Afghanistan’s Badakhshan Province. It is administered from the Provincial capital of Fayzabad, a city of 50,000 recently taken over by the Taliban. As of 2020, the Wakhan Corridor had 13,500 inhabitants. The northern part of the Wakhan, populated by the Wakhi and Pamiri tribes, is also referred to as the Pamir.

The China-Afghanistan Border Crossings

There are three main border crossings between Afghanistan and China, although the entire region is crisscrossed with difficult, single donkey tracks. These routes are all generally inaccessible during the winter months. None of the three main crossings are developed, except to provide border security access, although they do permit the summer cross-border passage of locals. We discuss these as follows:

The Chalachigu Valley

The Chalachigu Valley runs east of the Wakhjir Pass on the Chinese side and connects with Taghdumbash Pamir and the Wakhan Corridor. The Chalachigu Valley is about 100 km in length and is the source of the Taxkorgan River, which runs into China and is a significant water source, ranging from 1 km to 5 km wide. The entire valley on the Chinese side is closed to visitors; however, residents, and herders from the area are permitted access. Often these locals can be seen acting as traders at the Kashgar livestock market, which has been operational for thousands of years and is the largest in Central Asia.

The Wakhjir Pass

The Wakhjir Pass is at the eastern end of the Wakhan Corridor and is the only navigable pass between Afghanistan and China at this current time. It links connects Wakhan with China’s Taxkorgan Tajik Autonomous County in Xinjiang and has an altitude of 4,923 meters (16,152 ft). It is not an official border crossing point. China refers to the pass as the South Wakhjir Pass as there is a North Wakhjir Pass (the Tegermansu Pass) on the Chinese side.

There is no road along the Wakhjir Pass, it is purely a cut dirt track. On the Chinese side, the immediate region is only accessible to military personnel. An access road has been built for use by border guards, leading to the Karakoram Highway 80 kilometers to the east. On the Afghan side, the nearest road is a rough road to Sarhad-e-Wakhan about 100 kilometers west from the Wakhjir Pass accessible by other connecting paths. Crossing is only really possible by pack animals or heavy-duty SUV and is generally only accessible for seven months of the year (April to October). There are very few records of successful crossings by foreigners. although the British-Hungarian explorer Ariel Stein has written an account of it. Historically, the pass was a trading route between Badakhshan (Afghanistan) and Yarkand (Xinjiang) used by merchants from Bajaor (Pakistan).

The North Wakhjir (Tegermansu) Pass

The North Wakhjir, or Tegermansu Pass is a closed mountain pass on the border between Afghanistan and China in the Pamir mountain ranges. It traverses the Tegermansu Valley on the Eastern end of the Little Pamir mountains and the Chalachigu Valley in Xinjiang. Historically, it was one of the three routes between China and Wakhan. On Chinese side, there is a Chinese border post in the valley below. There have been proposals and plans by the Kashgar Regional Government to open this pass as an inland port, however this has yet to be approved. It is at an elevation of 4,827 meters.

The Current Situation At China’s Border With Afghanistan

Security and surveillance all along the Chinese border has been stepped up with initial plans to do so going back months. Part of the current situation with certain Uyghur factions being detained in China is to do with the possibility of unrest, although the radicalization of Uyghurs is more likely to come from Pakistan to the south, where the connectivity infrastructure, via both the Karakorum Highway and direct air connections to Islamabad are far better than connectivity between Afghanistan and China. There is little chance of any Taliban or other encroachment into China from the Afghanistan border as activity can easily be spotted and the terrain is extremely difficult.

Usually, at the Kashgar market, and especially the livestock market, traders do business having crossed the mountain passes under strict supervision from the Chinese border guards and the local PLA. They will typically bring Afghanistan products in addition to local herbs, plants and so on that can fetch a high price in China. Pack animals such as Donkeys, Yak and occasionally Camels are all traded here as are Fat-Tailed Sheep and rarer creatures such as Snow Leopard skins. Often these are resold onto Chinese traders, some bartering takes place with electronic and other products being taken back across and into Afghanistan. Security at present remains extremely tight.

British Armchair media has reported that “For the Taliban, the opening up of the border with China at the end of the Wakhan Corridor…” yet clearly, they are reporting on areas they have never been do and even less understand. Such is the journalistic dross one now has to contend with. Where are the impartial War Reporters? Where is Afghanistan’s Hemingway, Michael David Herr, or Martin Fletcher?

Chinese Belt & Road Infrastructure Access To Afghanistan

The three current passes, especially the Chalagigu Valley and the South Wakhijir Pass present extreme engineering and construction challenges to make viable for either road or rail. The Pamir mountain range is unstable and prone to landslips – the Karakoram Highway to Pakistan is regularly disrupted due to rockfalls. In addition, the winter months – from October to March – render these inoperable due to the extreme conditions. There is no economic justification for developing either of these two routes.

It would be possible to develop the North Wakhijir (Tegermansu) Pass and the Chinese military already have built an access road from the Karakoram Highway along an 80km route to within 6km of the border, where it becomes passable by smaller vehicles only. A small supporting garrison village sits at the border crossing inhabited by military personnel. It would be feasible to further extend that pass into Afghanistan and to the Badakhshan Provincial capital of Fayzabad, a distance of about 450km. This would open and develop Afghan-China trade, however the extent of this being economically viable is very much up in the air at present.

Alternative China-Afghanistan Belt And Road Connectivity

In fact, there are existing connections – but not with Afghanistan directly. Road connectivity runs from China’s border with Tajikistan at the border crossing at the Karasu Inland Port of Entry over the Kulma Pass, at an elevation of 4.36km above sea level. From here, the rugged AH66 route leads from connections from China’s Karakoram Highway (Kashgar and Urumqi) and over the Pamir mountains eventually to the Tajik capital, Dushanbe. It is only open for two weeks each month (16th to the 30th) from May to November as constant landslides require continual maintenance and the route requires constant repair and clearance.

However, these connect through to Tajikistan’s four border crossings with Afghanistan’s Badakhshan Province and onto Fayzabad, and are the most used China-Afghanistan haulage routes. The Afghanistan-Tajikistan border is almost entirely marked by the dividing Panj, Pamir and Oxus Rivers; with the only practical border crossing into Afghanistan via bridges.

The first bridge crossing the Tajik-Afghan border was opened in November 2002 and connects Tem in Tajikistan to Demogan in Afghanistan. A second bridge was opened in July 2004, known as the Tajikistan–Afghanistan Friendship Bridge, which connects the two banks of the Darvaz Region across the Panj River (which further downstream flows into the Oxus) at the town of Qal’ai Khumb in Tajikistan. Qal’ai Khumb is an important overnight rest stop in Tajikistan and Afghanistan and is 368 km from the Tajik capital, Dushanbe. On the Afghan border Kalai-Khumb has one of the three bridges over the Panj river. In the past a Sunday market used to take place here to trade goods with Afghanistan.

The Panj River bridge between Afghanistan & Tajikistan

A third bridge, spanning the Panj river, connects Panji Poyon in Tajikistan to Sherkhan Bandar in Afghanistan’s Kunduz Province to the West of Badakhshan and was opened in August 2007. The fourth river crossing between Afghanistan and Tajikistan is again across the Panj river, at Vanj in Tajikistan’s Gorno Badakhshan to the Afghan Province of Badakhshan and onto Fayzabad.

All these border crossings are currently closed and are controlled by the Taliban. It is understood that Tajik, Russian, and Chinese security forces are currently present in these areas.

It would be possible to expand and develop infrastructure build, especially the existing roads and bridges connecting China, Tajikistan, and Afghanistan. This would undoubtedly increase bilateral and trilateral trade between Afghanistan, Tajikistan, and China. However, with the Afghani economy currently ruined and the country in a state of significant instability, such builds will not take place or be financed until the situation calms down.

However, this does not necessarily mean that China and Tajikistan will not build and develop BRI infrastructure that could later also be deployed to service future potential Afghan trade.

The Kyrgyzstan Connectivity Route

There have been discussions about connecting Tajikistan with China via rail, although a direct route over the Pamir is almost impossible to build. Instead, a route into Tajikistan via the countries northern border with Kyrgyzstan is being considered. China’s national railway network extends as far as Kashgar (with additional talk of extending that south to Gilgit in Pakistan) with plans to link that line through to Kyrgyzstan.

A 2012 plan was devised to build almost 50 tunnels and close to 100 bridges, with a total length of 500 km. The line would traverse mountainous terrain, some sections over 3,000 meters above sea-level, with new construction of approximately 280km of track in Kyrgyzstan and about 180 km in China. The proposed line would run to Osh, a major trading city in Kyrgyzstan, and west into Uzbekistan. From Osh a spur would head south across the Kyrgyz-Tajik border to Dushanbe.

Tajikistan does have a small rail network, terminating in Dushanbe, with links to Uzbekistan and ultimately to Moscow. There has also been talk of a Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Tajikistan (TAT) railway that would link through west to Iran and the International North South Transportation Corridor. These plans may one day come to fruition, if not for the huge expense, but in following both China and Russia’s desire to bring regional peace to this entire region through the promotion of trade.

The Pakistan Connectivity Route

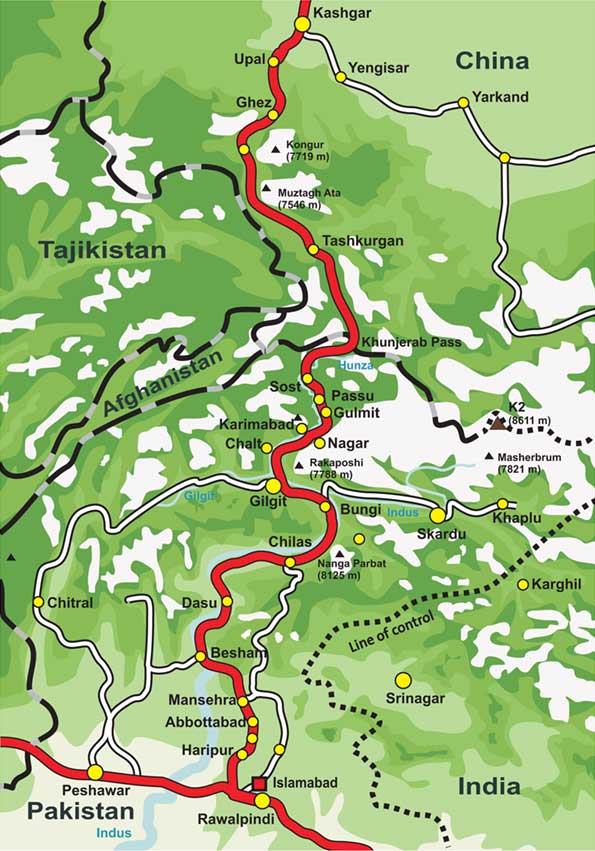

It is the southern Afghanistan connectivity that is likely to be developed first due to the northern routes via Wakhan, Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan being difficult and expensive, although that’s not to say they may not eventually happen. A more likely scenario for China to access Afghanistan is to expand and develop the existing road network through from Taxkorgan in Southern Xinjiang across the border to Pakistan and Gilgit. This route, the Karakorum Highway, already exists and has been in use for decades, although it too is subject to weather extremes, the terrain is rather easier to engineer. This route, known as Highway 314 in China and the N35 in Pakistan, extends through from China as far as Islamabad, the Pakistan capital. A route from Islamabad, the N5, connects through to Peshawar.

There has been significant discussions to extending the existing Chinese railway, which runs through to Kashgar and Yarkand, through the same Khunjerab Pass to Gilgit, on the Pakistan side, which has national rail connectivity to the rest of Pakistan. In 2014, China commissioned a “preliminary research study” to build an international rail link to Pakistan. In 2016 this 682 km proposed railway link was reported to be part of the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) and was to commence construction during the second phase of CPEC between 2018-2022. However, the construction of this railway line was not mentioned in the CPEC Long Term Plan from 2017-2030 released jointly by China and Pakistan in 2017. China’s involvement in several rail projects in Pakistan is motivated primarily by commercial considerations, but it also sees distinct advantages for its improved transportation and access to Central Asia and the Persian Gulf, as Pakistan’s national rail network connects through to Pakistan’s Seaports at Karachi and Gwadar. Significant new investment has taken place at Gwadar to cater for Afghani trade, while China has also been developing Special Economic Zones in the Punjab region near Afghanistan.

The Peshawar-Kabul Connection

The Peshawar connection is also highly valuable. This is already operational as it is part of the Turkmenistan-Afghanistan-Pakistan-India (TAPI) gas pipeline that bisects Afghanistan running West to East. That is supported by an existing road network providing maintenance and some trade between Afghanistan and Pakistan. Pakistan’s N5 highway runs from Islamabad to Peshawar and onto the Afghan border at Landi Kotal on the Khyber Pass to Afghanistan. From there it is now known as the AH76 which connects directly to Kabul – a five and a half hour drive.

The Afghanistan-CPEC Corridor

It is for these reasons that an extension of CPEC into Afghanistan and directly to Kabul looks the most likely option, while China’s Belt and Road connectivity with Afghanistan from its direct borders looks a longer-term play. The Wakham Corridor itself is only sparsely populated and at present offers minimal opportunities – unless any viable mineral extractions are within the region.

Accordingly, while China’s Pamir infrastructure build with Tajikistan and Kyrgyzstan can be expected to include the potential for future Afghan routes, a simpler, and less expensive solution for China to access Afghanistan is via the Khunjerab Pass from Kashgar into Pakistan and improving the existing Friendship Highway with links through to Islamabad and Peshawar. That can be expected to be augmented with a reappearance of the proposed Kashgar-Gilgit railway with improvements also to be made to the Pakistan national rail network from Gilgit to Peshawar as part of this. Connectivity from Peshawar to Kabul then makes sense.

Related Reading

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com