New Lhasa-Nyingchi Rail Could Eventually Reopen Tibetan Trade Routes With India

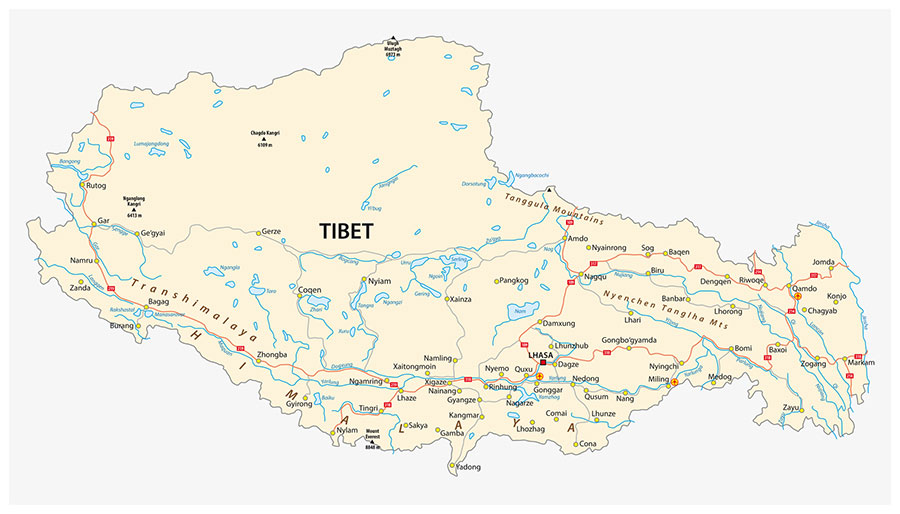

Tibet has opened its first electrified railway line, a route leading from the TAR capital Lhasa, through to Nyingchi, close to the border with the India state Arunachal Pradesh. I have been to this region, with India just across from the confluence of the Bramaputra and Tibet Rivers.

Eventually the Nyingchi line is planned to extend further east and connect with railway lines leading to Chengdu in Sichuan Province. What could happen in time however is a route heading south, into India and onto the Arunachal Pradesh capital city, Itanagar. That is connected to the Indian national railway and will later provide connectivity to Tawang, near the border to Bhutan under rail development plans outlined by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi. That is expected to be completed in 2026.

Arunachal Pradesh is also connected by road to Myanmar with railway also being considered for a route which would again reconnect old trade routes between Tibet and what was Burma.

While any rail connectivity between Tibet and India is conjecture at present, such a route would make it possible to travel by train from New Delhi to Beijing. It would also considerably boost China-India trade as especially the economies of Tibet and Arunachal Pradesh. New Delhi may view that as a requirement – Arunachal Pradesh has India’s third lowest GDP at US$3.8 billion, from a population of abut 1.5 million. It also has problematic educational and trade facilities yet is faced just across the border with China with gleaming new Tibetan infrastructure. Tibet’s GDP is nearly seven times higher than Arunachal Pradesh at US$28 billion from a population nearly three times larger at 3.7 million. Tibetan’s are also wealthier, with an average GDP per capita of US$7,000 per annum against Arunachal Pradesh’s US$2,000.

That has the potential to create unrest – holding onto the state may require some diplomatic and infrastructure solutions to be put in place, and a decision to increase the wealth of Arunachal Pradesh natives by permitting trade routes to reopen.

China would also welcome an increase in trade via Tibet, not least to deflect Tibetans away from the influence of the Dalai Lama by raising living standards. Tibet has the lowest GDP amongst all of China’s regions, although GDP per capita has been rising of late.

Border disputes need to be overcome first. China claims part of Arunachal Pradesh as part of Tibet, the result of a somewhat muddled British instigated border demarcation between Tibet and India (the McMahon Line) dating to 1914, although it does recognize a very similar border distinction ‘The Actual Line Of Control’ which was agreed with Chinese Prime Minister Zhou Enlai in 1959. Nonetheless, the McMahon line is still the current border. Tawang, with a population of 11,000, is the principal disputed area, across the border from the Tibetan town of Dichu, a small town but home to a sizeable Chinese military garrison.

China has been stepping up pressure for India to reach some conclusion over the border. Also, near to Tawang is the Bhutan border and the Sakteng Wildlife Sanctuary, which China has also stated was a ‘disputed territory’ last year, further ratcheting up pressure on New Delhi.

Concerns in the Indian parliament are that in opening trade and putting in infrastructure on the border with China, the Chinese military ‘would just walk in’. That occurred in 1962 in the short-lived Sino-India war, which China won, occupying Dawang, yet later withdrew. Recent border clashes at Ladakh some 3,000km to the West have further complicated matters.

Nonetheless, an ultimately sensible solution, assuming China and India can reach a border agreement, would be to link the Tibetan towns of Nyingchi and Dichu to Indian railways. That would further boost Tibet’s economy and reestablish old trade routes, through India and potentially reconnect with the Bangladeshi Port at Dhaka, for centuries the main seaport access to and from Lhasa.

There is some border trade between Arunachal Pradesh and Tibet, conducted through crossings at Anjaw (near Nyingchi), Tawang, West and Upper Siang, and Upper Subansiri. Opening the region to full border trade has also been evaluated by the Indian Chamber of Commerce, albeit back in 2003, when a study found that doing so would boost China-India trade by 20%, which if correct would increase bilateral trade today by some US$18 billion.

Arunachal Pradesh’s economy is largely agrarian, based on the terraced farming of rice and the cultivation of crops such as maize, millet, wheat, pulses, sugarcane, ginger, oilseeds, cereals, potato, and pineapple. In 2019 total horticulture production reached 190.70 thousand metric tonnes (MT). Other key industries include art and crafts, weaving, cane and bamboo, horticulture, power, and mineral based industry. Due to its topography, the state has varied agro-climatic conditions suitable for horticulture of flowers, aromatic and medicinal plants.

Tibet has an industrial base including tourism, Tibetan medicine, plateau specific biology, handicrafts, and mining. After the opening of the Qinghai‑Tibet railway and the reopening of Nathu La trade pass, service industries such as trade and transportation have also developed. The region has been increasingly industrialized with Tibetan businesses such as bottled water, traditional Tibetan medicine, the processing of agricultural products and other materials all being publicly listed on Chinese bourses.

Both sides have been in discussions over a resolution to the border dispute since 1960, which includes other areas in addition to Arunachal Pradesh. China made a “package” offer in 1960, which again came to the table in 1980–85. In this, China “would be prepared to accept an alignment in Eastern Arunachal Pradesh, in general conforming to the McMahon Line, but India would have to concede Aksai Chin, a high-altitude desert area close to Xinjiang Province and Ladakh to China. Other Tibet-India areas under dispute have been regarded as “relatively minor and manageable.” This package would see China occupy 26% of the disputed land. In hindsight, it would have been wiser for India to have agreed to this at the time, there being little commercial value in Aksai Chin, but significant potential agricultural and trade value in Arunachal Pradesh.

In 1985 China made modifications to the package – “the Indian side would have to make significant and meaningful concessions in Eastern Arunachal Pradesh, for which China would make corresponding concessions in Aksai China. Tawang was brought up “as indispensable to any boundary settlement”. These changes in the package proposal by China remained until 2015 with little attempt by India to rectify them – one reason for Chinese impatience and the more recent border clashes.

Meanwhile the impasse continues, although it can only be a matter of time before the sheer commercial value of linking trade between Tibet and India occurs. Both sides would benefit. Meanwhile, India is playing a dangerous game in having a commercially backward region remain undeveloped next to a Tibetan region with 2020 GDP growth at 7.8%. It is not a sustainable option before the local Arunachal Pradesh population would begin to look for Chinese investment and wealth if India cannot or will not deliver.

Related Reading

About Us

Silk Road Briefing is written by Dezan Shira & Associates. The firm has 28 offices throughout Asia, and assists foreign investors into the region. For strategic advisory and business intelligence issues please contact the firm at silkroad@dezshira.com or visit www.dezshira.com